Publications /

Opinion

Earlier this month, U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen told congressional leaders that the government could run out of cash as early as June 1, if the debt ceiling is not raised in time. In January, the Treasury reached the current legally established ceiling in nominal terms ($31.46 trillion). The funds currently available to make government payment flows tend to exhaust by the end of this month.

According to the Treasury Department:

“Failing to increase the debt limit would have catastrophic economic consequences. It would cause the government to default on its legal obligations—an unprecedented event in American history. That would precipitate another financial crisis and threaten the jobs and savings of everyday Americans—putting the United States right back in a deep economic hole, just as the country is recovering from the recent recession.”

The nominal debt ceiling is a crude and rudimentary barrier against excess public debt in the United States. After all, inflation shrinks its real value. Furthermore, its rise naturally accompanies the GDP increase in absolute terms, the expansion of government functions and the desire for accumulation of such debt by buyers of bonds considered as low-risk ‘safe haven’ for investors in the world—at least when there is no self-imposed damage by the nominal debt limit.

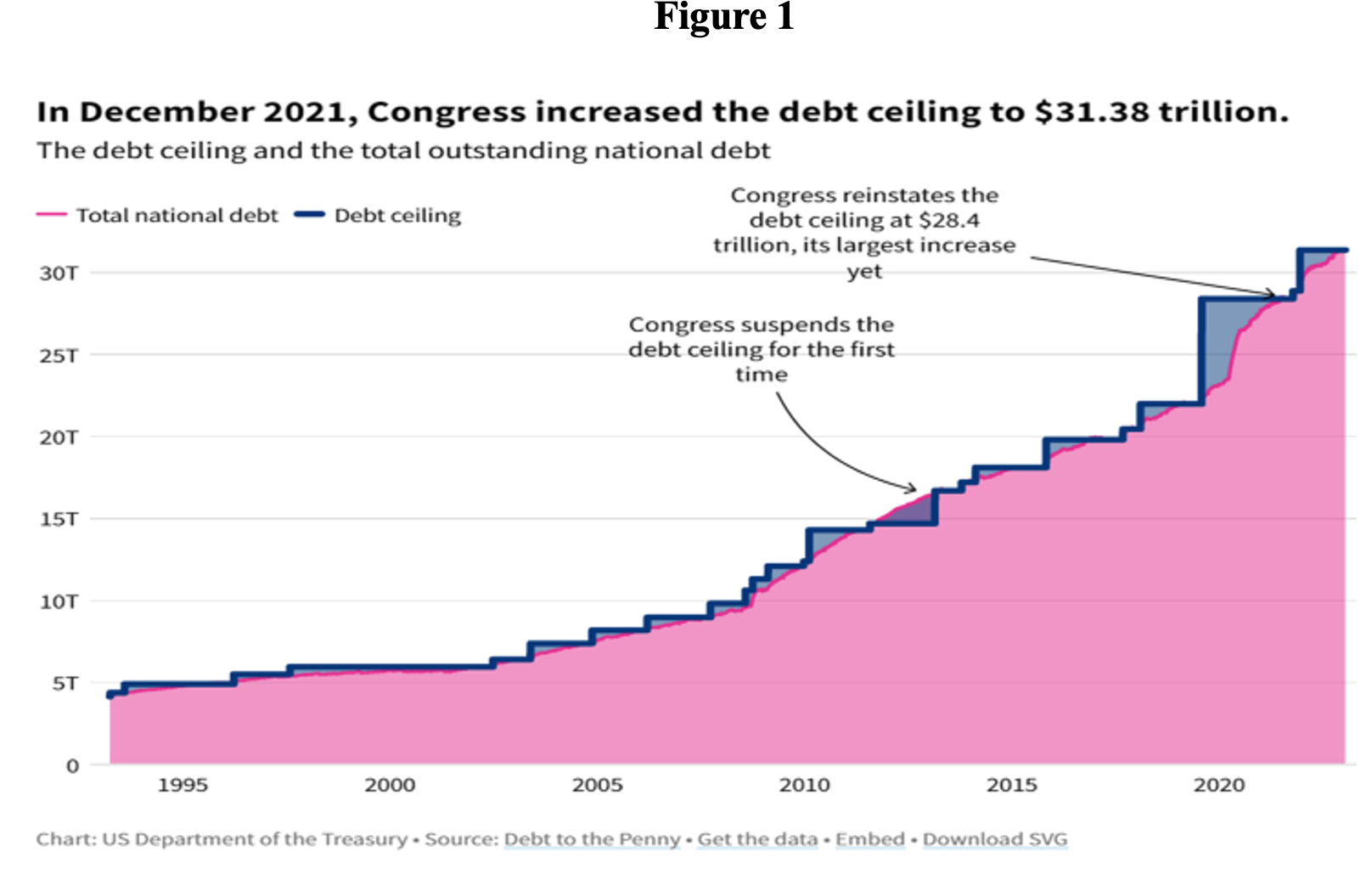

In fact, the debt ceiling dates to 1939, when Congress consolidated various forms of debt into one aggregate amount. Since then, the debt limit has been consistently increased each time the stock of public debt approached the limit.

As the Treasury has noted, since 1960 the debt limit has been raised in some form 78 times, to avoid defaulting on Treasury interest payments and keep the government working. These limit increases have happened 49 times under Republican presidents and 29 times under Democrat presidents. Figure 1 shows the increases since the mid-1990s, up to the most recent in 2021.

Sometimes, noise and turbulence accompany the raising of the debt ceiling. In 1979, for example, the Treasury had to delay bond payments. A rule was then established allowing the House to automatically increase the debt limit through budget resolution without requiring a separate vote. This rule was used 15 times to increase the debt limit.

However, that rule was repealed in 2011, when the Obama Administration faced a Congress with a strong presence of the Republican Tea Party. Subsequently, there have been prolonged battles over raising the debt ceiling in 2011, 2013, and 2021. Not during the Trump Administration though! It is important to note that the 2011 episode even resulted in the downgrading of the U.S. credit rating by S&P, from the maximum AAA level to AA+, where it remains.

The U.S. is, therefore, currently undergoing a repetition of those moments of tension because of an initial impasse in the congressional decision to postpone or ease the ceiling restriction. Republicans, with a slight majority in the House, managed to pass a bill in late April that would increase the debt ceiling by $1.5 trillion and kick the risk down the road until next year. But it came with the counterpart of reduced expenses in programs very high in priority for the Democrats. It would not be accepted by the mostly Democratic Senate or by the White House.

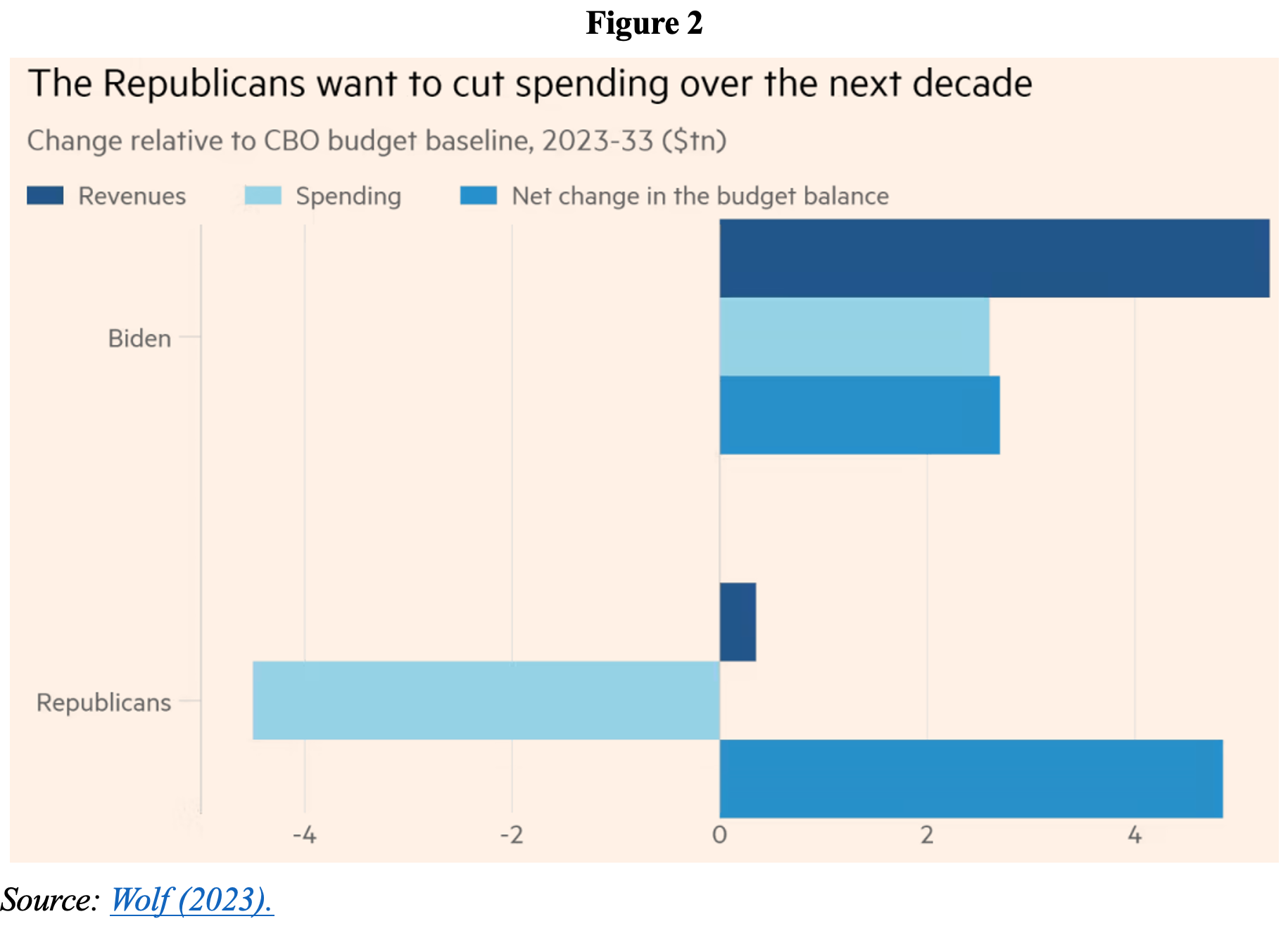

Hope remains that the White House and Republicans will reach a deal in time to avoid what Yellen called “unthinkable” and “catastrophic”. At the heart of the talks are limits on domestic spending, with Republicans demanding deep cuts to many programs over the next 10 years, while Democrats would accept more modest cuts for two years. Figure 2 compares the stances of the two main parties.

The White House rejects the Republican demand for the rollback of clean energy tax credits that were passed last year in the Inflation Reduction Act. Nor does it accept cuts to student debt relief measures, or the establishment of work requirements in programs against poverty and in the social safety net, as the Republicans also want.

If there is no agreement in time, the Treasury would be forced to delay salary payments, temporarily close some public activities and, at the limit, default on debt interest payments. In the event of any further downgrading of the credit rating by any agency other than S&P, many asset managers would be forced to pull U.S. Treasuries out of their AAA asset pools.

To give an idea of the perception of default risks by the markets, U.S. credit default swaps (CDS)—derivatives that work as insurance and pay if a company, or country, defaults on its loans—for one-year Treasury bonds were, in mid-May, higher than the equivalents for Greece, Mexico, and Brazil (Figure 3). For longer maturities, such as five years, the situation was not so abnormal. But spreads between 1-month and 3-month Treasuries hit a record high of up to 180 basis points. Not by chance, news about positive conversations between the two sides led to US futures and European equities rising on May 18, as investors grew more confident that a U.S. government default would be averted.

Source: Wolf (2023).

On May 11, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) drew attention to the serious consequences for the country and the global economy of any default by the U.S. public sector, even if temporary. No one can say what the chain reactions of a shock to the very low risk ‘safe haven’ of global finance would be.

As if the shocks suffered during the “perfect storm” of recent years were not enough! The difference, however, is that in this case, it is not a matter of markets suspending debt rollover because they consider it insolvent, but of a politically self-imposed barrier by the country itself. The occasional murmurings by Republicans—including former President Trump—that a default and market turbulence may be an adequate price to obtain public spending cuts are of concern.

There are legal devices that correspond to ways to circumvent the ceiling and avoid what would be the first default by the federal government in the history of the country: issuing platinum currency worth $1 trillion, with its deposit at the Federal Reserve, or an appeal to the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, where there is mention of the possibility of issuing debt to pay commitments without passing through Congress. Such devices, however, are legally contestable and have been considered as “bad options” by Secretary Yellen and as “loathsome” by Fed Governor Jerome Powell. An agreement with Congress on the debt ceiling remains the only suitable option.

Concern about the trajectory of U.S. public debt was contained while the period of low interest rates lasted, particularly when these were lower than the GDP growth rate, as Olivier Blanchard has always emphasized. Now, what several voices, including Glen Hubbard and others, have advocated makes sense: the establishment of a fiscal framework to deal with the matter, instead of nominal spending caps. But this transition need not happen via financial shocks and a possible default on public debt. The last part of May remains a deadline for an agreement on lifting the nominal debt ceiling to avoid “unthinkable” upheaval.