Publications /

Policy Brief

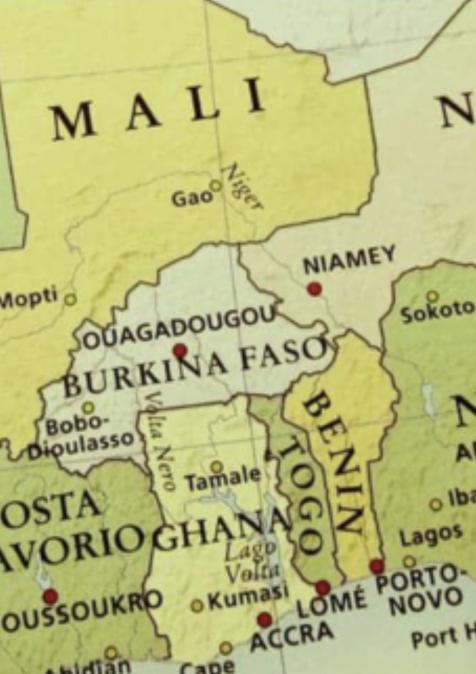

The start of 2025 was marked by the official departures of Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). Now joined in a new organization, the Alliance of Sahel States (Alliance des États du Sahel, AES), the three countries have left ECOWAS facing a legitimacy crisis and concerns for its future.

How these blocs decide to interact with each other will greatly influence the future of regional stability and foreign engagements. A divided West Africa will affect counterterrorism operations, trade, and governance partnerships, forcing external powers, including the European Union, United States, Russia, China, the Gulf states, Türkiye, and India, to rethink their roles in the region. The second Trump administration adds complexity to this equation, as it has started off by implementing an unpredictable foreign policy, causing shocks to multilateral and global foreign engagement.

What Lies Ahead For The Region?

Shifting from a security alliance, formed in 2023, to a confederation in 2024, AES prioritizes collective defense and mutual assistance, focusing on a desire for self-reliance in security matters. Its creation reflects the profound dissatisfaction with ECOWAS’s approach to political and security crises. The regional landscape is increasingly divided into two blocs. On one side, the Sahelian interim governments are working to reinforce a shared identity, as seen in initiatives such as the unveiling of a shared biometric passport to facilitate mobility within the AES bloc. On the other side, ECOWAS receives recurring criticism for its zero-tolerance policy for unconstitutional coups, and its inconsistent enforcement across its member states. In the 2024 Senegalese elections, for example, ECOWAS failed to act firmly in response to President Macky Sall's attempts to delay electoral processes, revealing selective application of its principles.

The geopolitical shift does not only affect regional dynamics but is also echoed in the diverging international alignments of the AES and ECOWAS. At conception, ECOWAS was founded on Pan-Africanism and non-alignment values, striving for regional self-determination and independence from external superpowers. During the Cold War, its members adhered to the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), resisting foreign interference, particularly by France.

The zero-tolerance policy for unconstitutional coups was one in a series of principles established in the 2001 ECOWAS Protocol on Democracy and Good Governance, which moved the region closer to Western neoliberal norms. A key foundation to uphold democratic unity in the region, it was put in place to promote rule of law, good governance, norms on free elections, political pluralism, judicial independence, civil liberties, and anti-corruption. But this has branded ECOWAS as a tool of Western powers, with, in particular, resentment against the former colonial power France adding to the growing tension between member states that view this proximity as a threat to their sovereignty. Trade, security, and governance cooperation are the modern constructs of the complex historically heavy relationship between ECOWAS and Western allies including the US, EU, and international financial institutions. Many of these frameworks and agreements have on top of the essential purpose been linked to normative conditionalities, promoting liberal democratic principles, as seen with initiatives including the European Peace Facility, Power Africa, and Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs). So, although they show continuous Western engagement, these various initiatives have frequently been criticized for putting external goals ahead of domestic ones.

When announcing their departure from ECOWAS, the military-led AES was adamant that it was breaking away from its former colonial powers, and has increasingly aligned with Russia, seeking military and technical support. This shift coincides with rising anti-French and anti-Western sentiment, exacerbated by the presence of Russian paramilitary groups such as the Wagner Group (now Africa Corps). Some reports indicate that the AES could also strengthen ties with other anti-Western states, including China and Iran, further deepening its geopolitical realignment.

This division mirrors a Cold War-style geopolitical rivalry, in which Western powers could instrumentalize regional rifts to their benefit. The fragmentation threatens ECOWAS’s founding principles and poses security and economic risks. Yet, despite these tensions, both blocs may need to cooperate because of their shared economic and security interests, including trade and counterterrorism. The future of West Africa hinges on whether these factions can settle their differences or remain entrenched in opposing global alliances.

Although, ECOWAS remains a pivotal player in West African economic integration, and continues to be a reference point for regional cooperation, particularly in the areas of free movement and the customs union, in place since 1979, the blow remains hard. The viability of the AES bloc is also questionable, particularly as all three member states have limited access to seaports, which will have a direct impact on their highly reliant agricultural and extractive industries. Essentially, these two institutions will have to coexist, but what does this mean for foreign engagement?

With that in mind, three possible scenarios could play out, each with far-reaching consequences for regional actors and foreign powers.

Scenario 1: A Hard Split, Competing Blocs, and Geopolitical Rivalry

The evident ideological gap between ECOWAS and the AES makes the possibility of a hard break seem likely. An important element to highlight is that the fragmentation within ECOWAS is felt between Sahelian, landlocked states and coastal countries. This division has deepened with the diplomatic tension between Burkina Faso and Ivory Coast, as President Traoré of Burkina Faso accused both Benin and Ivory Coast of having French military installations close to their borders with the intention of destabilizing Burkina Faso. Côte d'Ivoire is viewed as one of the last bastions for redesigned Western military operations, as the various military presences of France, the U.S., and UN in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, decline. As a strategy to increase defense cooperation and technology exchange in the Sahel, non-western countries including Russia, China, Iran, and Turkey have taken advantage of this Western backslide by increasing their respective bilateral military agreements with the AES.

Notwithstanding the challenges it faces, ECOWAS retains strong military backing from the U.S. Congress, the EU, and international financial institutions. In 2020, the EU’s European Peace Facility (EPF) allocated over €600 million for military support in the Sahel. But most of these funds were redirected to the Ukrainian conflict and only 6% of the fund has since been used to support security initiatives in the Sahel.

The U.S. administration in 2005 committed to the Trans-Sahara Counterterrorism Partnership (TSCTP), an initiative to counter terrorist influences in the region of which Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso and other ECOWAS states were part. However, President Trump has shown little regard for security initiatives abroad or multilateralism, and since the abrupt USAID cuts, attention is now turning to the possible reduction of the U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM), which is responsible for the TSCTP. Trump is more likely to seek bilateral trade agreements, which could benefit the AES countries. For example, their rich soils may be of interest to Trump, which could help them regain access to the American market through initiatives such as the African Growth Opportunity Act (AGOA).

While AES countries have rejected some Western-led development frameworks, they are engaging increasingly with China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), maintaining China as a dominant economic actor in the region. Of the multiple MoU’s between the AES and China, Burkina Faso signed in September 2023 a concessional loan agreement with Export-Import Bank of China to construct a 25 megawatt peak (MWp) solar power plant. These engagements showcase how the AES states are seeking alternative economic and security guarantees outside the ECOWAS framework.

The impact on regional economies is significant. With AES pivoting towards non-Western partners, cross-border and international trade within West Africa’s supply chains could be disrupted. Niger’s recent uranium export restrictions have coincided with exploratory talks with Rosatom, Russia’s state nuclear agency, potentially signaling new agreements outside traditional French channels.

In this situation, the EU is more and more isolated, and struggles to offset rising Russian and Chinese influence with the U.S. pulling out. As certain Western actors attempt to adjust their approaches, rising powers, including Türkiye, India, and the Gulf states reinforce their positions as alternative partners. This raises the possibility of selective cooperation, in which case, as the next scenario explores, shared interests may overcome strict bloc dynamics.

Scenario 2: Coexisting Through Ad-Hoc Cooperation

Unlike a complete break, this scenario would see ECOWAS and AES continuing to operate in parallel, engaging in practical, issue-specific cooperation where mutual interests align, particularly in trade, migration, and security. While maintaining their independence in terms of national policy and military, AES countries would continue to take part in economic efforts, and may still rely on ECOWAS trade routes for imports and exports that benefit both blocs. Ad-hoc cooperation is not new for the region; coalitions including the G5 Sahel and the Accra Initiative have overseen West African security, and the AES and ECOWAS might reach similar agreements. The attempt by ECOWAS to extend an olive branch by suggesting a six-month window of opportunity for the AES countries to rejoin the organization is one factor driving in this direction. This signals that diplomatic hope is still alive and there is willingness to maintain positive relations between the two organizations.

In this landscape of selective collaboration, middle powers such as the Gulf states, India, and Türkiye could see new opportunities to deepen engagement with both ECOWAS and AES countries, adapting their strategies to the changing political realities. Although often overlooked, these actors have been present in Africa since the 1990s, and now must strike a delicate balance between aligning their interests with African governments, and navigating relationships with global powers including Russia, China, and the West.

Among the Gulf Cooperation Council countries (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates), Qatar voiced “concern” about the Niger coup, but Saudi Arabia and the UAE issued tougher statements, showing a disparity in GCC members’ positions. So, as the GCC navigates these varied degrees of response, a non-confrontational split between the AES and ECOWAS is welcome as it provides opportunity for Gulf states to increase their presence while protecting their interests.

The Gulf states are deepening their economic footprint in West Africa through targeted investments. The UAE has committed $19 billion to transport and energy projects in Niger, alongside $500 million in Mali’s gold, transport, and energy projects. Saudi Arabia and Qatar prioritize rural development, agriculture, and energy, with Saudi Arabia pledging $325 million in Mali, including a 2023 MoU to enhance air transport. Across ECOWAS, Saudi Arabia has invested $120 million in transit, education, and healthcare, notably the Bouna-Doropo-Burkina Faso Border Road in Côte d'Ivoire. Meanwhile, in Ghana, the UAE has renewed its $3 billion commitment to energy, agriculture, education, healthcare, real estate, and tourism. These strategic investments illustrate the Gulf states’ growing roles in fostering economic development and long-term partnerships in the region.

The U.S., Russia, and China are likely to pursue transactional or parallel engagements along this path of ad-hoc cooperation between ECOWAS and the AES, concentrating only on their strategic interest rather than bloc loyalty. As bilateral aid from nations such as Belgium, and development aid programs like the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MSS), are being restructured or curtailed, the increasing participation of middle powers presents both organizations with a great chance to broaden their alliances. The presence of several investors in West Africa could provide comfort to the European Union when the U.S. seems to be redefining the transatlantic partnership, leaving the EU to fill a gap it cannot handle on its own.

Scenario 3: Weak AES, Weakened ECOWAS, Fragmented West Africa

A third scenario would see a fragmented region in which ECOWAS loses coherence as its member states form independent deals with AES countries and external actors, bypassing the regional entity. This would undermine ECOWAS as a united decision-making body, producing an incoherent regional scheme, due to overlapping and competing diplomatic and economic policies. In turn, this would limit ECOWAS’s capacity to apply consistent overarching regional policies on security, commerce, and governance. Signs of a feared greater regional fragmentation are seen in the Togolese rapprochement with AES. Selected as mediator by ECOWAS to negotiate the return of the three departing countries, the Togolese government has openly admitted its proximity with the AES security and regional mandate. Indeed, Togo maintains a warm relationship with the AES, as seen with its suggestion of the port of Lomé as an option to transit AES commodities, as opposed to the usual regional trade hub ports of Benin and Ghana. This has sparked fear that Togo could join the AES as its fourth member. Although only speculation, we see here the start of a multi-affiliation situation.

A weaker ECOWAS poses more than simply a security threat to the EU. It also threatens the existence of a regional partner prepared to support and adhere to democratic values, governance standards, and the conditions frequently associated with European involvement. Though the G5 Sahel has played a more important role in counterterrorism efforts than ECOWAS, the EU has leveraged ECOWAS as a soft power conduit to assist the spread through West Africa of its model of democratic governance, rule-based cooperation, and regional integration. The expulsion of French troops from several Sahelian countries already weakened France’s influence in the region; this would be the closing act. In response, the EU could attempt to shift to more selective bilateral and regional engagements, rather than regional integration, through its Global Gateway strategy, which focuses on infrastructure and energy cooperation. Given that anti-French sentiment appears to coincide with overall EU appreciation, the EU would most likely emphasize strengthening ties with stable, Western-aligned administrations, rather than attempting to shore-up ECOWAS cohesion.

As for the previous scenarios, China’s non-interference policy enables it to cooperate with both civilian and military administrations. Thanks to this, it is able to apply a non-normative stance to its engagement in Africa. It could easily step up its bilateral efforts to offer more critical minerals and infrastructure investments, especially in resource-rich nations such as Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso. This would be done through the BRI, which operates mostly through country-specific agreements, allowing China to navigate this new fragmented landscape. China could also use its soft-power tools, such as Confucius Institutes, to strengthen ties via bilateral agreements. Military partnerships would keep to their current format and be focused on specific countries, while adapting to West Africa's evolving security challenges.

Russia would see fragmentation as an opportunity to increase its influence by strengthening military connections with military-led regimes through arms sales, political support, and mercenary deployments. A lack of regional oversight would enable the Africa Corps to gain more ground in the Sahel region, given the military shortcomings of the region. As reports show, Russia’s strategy is weblike, touching mining efforts, as seen with Alpha Development and Marko Mining in Mali, military training, and media engagement. On this last point, Russia could be free to enhance its media influence in Africa by increasing funding for Russia Today and Sputnik, promoting storylines that undermine Western policies. Its aim is to increase the visibility of Russian perspectives, ultimately assuring greater transmission of its message, and positioning itself as a viable alternative to Western dominance.

The GCC would also focus on bilateral relations, prioritizing stable, resource-rich states. Economic diversification and food security would encourage targeted investments in agriculture, mining, and energy. Security engagement would be more selective, with aid increasingly contingent on alignment with GCC goals, while balancing relations with China, the West, and developing regional powers.

The Trump administration would be likely to maintain its transactional strategy, emphasizing U.S. economic and strategic interests, while opposing China. Bilateral agreements would prioritize the securing of critical mineral resources, which are a major priority in today's geopolitical context, as well as for U.S. national security and the private sector. This might be accomplished with the support of tools used to engage with African markets during Trump’s first term, such as the Development Finance Corporation (DFC) and the AGOA, if both are renewed by the end of 2025.

While this scenario is the most likely to create investment opportunities, it also risks deepening regional inequality and increasing geopolitical rivalries in West Africa.

Conclusion

West Africa’s future regional landscape is influenced by the changing dynamics between ECOWAS and AES, which influence the plans of domestic and external actors. From a domestic standpoint, these changes offer a chance to reclaim sovereignty and reshape alliances. But they also pose a risk of fragmentation. The difficulty for foreign players is to adjust their engagement tactics in a multipolar environment when their old allies might not be reliable partners. There are no obvious victors or losers in this shift. Instead, the results will depend on how each actor, whether domestic or international, adjusts to a quickly changing environment. Cooperation in the West African region is currently seeing all suggested scenarios at the same time. As the dust settles between ECOWAS and AES, the problem for external actors will not be picking sides, but navigating a new multipolar West Africa.