Publications /

Policy Brief

Fluctuating precipitation and extreme weather are long-standing features of life in West Africa, the Sahel, and the Lake Chad Basin. Communities across the region have historically adapted to these unique climatic conditions in diverse ways. However, the growing impact of climate change, coupled with challenges to food security and ecological resilience, has elevated these issues on the agendas of regional and international policy platforms. Despite this recognition, the region faces significant capacity-building needs and a lack of vertical integration of sub-national actors in climate strategy—both of which are essential to unlocking the transformative economic potential of climate action.

What the region needs now is not more high-level strategies, but concrete implementation. Climate has rightfully gained prominence among strategic priorities, yet actions continue to lag behind rhetoric. Local, regional, and national leaders must approach climate, environmental, and food system issues holistically—embedding them within the local sociocultural and economic context. Crucially, they must also acknowledge and address the role of resource management structures that perpetuate the vicious cycles linking climate stress and conflict.

Introduction

It is widely recognized in high-level international policy that climate change exacerbates security vulnerabilities and can intensify the risk of conflict. However, broad generalizations that directly link climate change to conflict risk oversimplify complex realities and can lead to misguided programming strategies. In West Africa, fluctuating precipitation and extreme weather are not new phenomena; communities have long adapted to the region’s diverse and challenging climatic conditions.[1] Today, the central policy question is how to ensure food security while sustainably transforming agriculture and food systems—an urgent priority at the intersection of climate resilience and human security.

This policy note builds on a series of three policy briefs analyzing the impacts of the August-October 2024 floods in the Lake Chad Basin, and the interlinked dynamics of conflict,[2] displacement,[3] and socioeconomic challenges[4] within the broader climate crisis. It aims to bring nuance to the prevailing narrative of climate change as a security threat in West Africa—particularly in the Sahel and Lake Chad Basin—by examining the policies, publications, and activities of international organizations, and assessing their effectiveness based on field research conducted for the earlier briefs.

For example, in a series of interviews on the links between climate shocks and displacement, both host and displaced families challenged the dominant narrative promoted by international donors—that displacement leads to tensions and violent conflict between communities. Instead, respondents emphasized that during crises, communities often demonstrate solidarity, even under severe resource constraints. While climate shocks like recent floods undoubtedly generate stress, the assumption that such stress inevitably leads to conflict and violence is reductive. It is not resource scarcity itself that drives insecurity—but weak governance.[5]

Context

The Sahel and the Lake Chad Basin have endured intense and complex armed conflicts for over a decade. In the Sahel—particularly Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso—deadly violence has persisted since 2011, driven mainly by violent extremist organizations (VEOs), state security apparatus, and ethnic militias. Similarly, in the Lake Chad Basin, parts of Nigeria, Niger, Chad, and Cameroon have faced overlapping conflict dynamics since 2010, with civilians bearing the brunt of the violence. These conflicts have resulted in thousands of deaths and the forced displacement of at least six million people. The roots of this instability lie in a combination of communal tensions and resource mismanagement. These dynamics are further exacerbated by a changing climate and increasingly frequent extreme weather events, placing the region among the most fragile in the world.[6]

In the second half of 2024, severe flooding struck the Lake Chad Basin, pushing the number of internally displaced persons (IDPs)—already over 3 million—even higher and fueling new socioeconomic tensions. Extreme weather events continue to strain livelihoods, particularly by threatening agricultural production, which remains a cornerstone of economic activity in West Africa and the Lake Chad Basin.

In West Africa, subsistence farming accounts for approximately 42.7% of total employment, while livestock is both a key economic asset and a symbol of cultural and financial capital. In the Lake Chad Basin, agriculture generates about 25% of regional income and employs 41% of the population.[7] Pastoralism and fishing, which follow agriculture as major sources of livelihood, are also severely impacted by climate shocks. Farmers face growing difficulties in cultivating their crops, while herders are forced to move livestock to less-affected areas, often intensifying competition over already limited natural resources. As flooding reduces the availability of arable land and pastures, land scarcity risks fueling both inter- and intra-community tensions.

Droughts and floods—two sides of the same climatic coin—compound these challenges. Rising temperatures accelerate evapotranspiration, leaving degraded soils unable to absorb, retain, or filter rainwater. Insufficient rainfall leads to crop failures, while heavy rains wash away farmland. These impacts are further aggravated by rapid population growth and the expansion of commercial agriculture, which increasingly relies on irrigation rather than natural water cycles. As environmental degradation accelerates, subsistence agriculture becomes more precarious, leaving already vulnerable communities increasingly exposed to the effects of climate change.

Mobility is a common adaptation strategy in response to gradual climate changes. In the face of shifting climates and economic challenges, local populations often resort to long-term regional migration or seasonal movement, typically following rainfall patterns. However, climate migration generally remains within regional borders; it rarely involves crossing national frontiers, distinguishing it from migration flows towards North Africa and Europe.

Policy assessment

Given these dynamics, climate change, food security, and ecological resilience have become pressing issues in international high-level policy discussions across regional and multinational organizations.

United Nations

The United Nations has several relevant initiatives aimed at addressing these challenges, including Security Council Resolutions, regional offices, expert groups, and strategic documents. For instance, UNSC Resolution 2349 (2017) (S/RES/2349), adopted unanimously, was the first to holistically recognize “the adverse effects of climate change and ecological changes among other factors on the stability of the region, including through water scarcity, drought, desertification, land degradation, and food insecurity, and emphasizes the need for adequate risk assessments and risk management strategies by governments and the United Nations relating to these factors.”

In 2024, the UN Security Council adopted a consensus Presidential Statement on West Africa and the Sahel, supporting the United Nations Office for West Africa and the Sahel (UNOWAS) (S/PRST/2024/3). This statement reiterated previous acknowledgements and encouraged UNOWAS “to scale up international action and support (…) to enhance the adaptive capacity of countries from the region and reduce their vulnerability to climate change” through humanitarian and development action, technology transfer, and capacity-building, including in renewable energy transition and energy efficiency. The document also recognized that climate change exacerbates conflict and called for long-term stabilization strategies.

UNOWAS[8] is a special political mission under the Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs (DPPA), based in Dakar. “It promotes good governance, respect for the rule of law, human rights and the mainstreaming of gender in conflict prevention and conflict management initiatives, as well as the women, peace and security and youth, peace and security agenda.”[9]

UNOWAS does not have a specific activity group focused on climate, environment, or food security. However, in 2022, it hosted a high-level Regional Conference on Climate Change, Peace and Security in West Africa and the Sahel, in collaboration with ECOWAS, in Dakar.[10] The event aimed to take stock of current efforts and strengthen responses, in line with the UN Security Council’s January 20, 2020 request to "take into consideration the adverse consequences of the climate change, energy poverty, ecological change and natural disasters on peace and security by supporting the governments of the sub-region and the United Nations system to carry out assessments of risk management strategies related to these changes.”

Chaired at the ministerial level, such diplomatic conferences—like high-level strategies and documents—are unlikely to significantly impact realities on the ground. While the high-level intention is evident, it appears to have little effect at the grassroots level. A 2013 Report of the Secretary-General on the situation in the Sahel region[11] reverts to the causal link between resource scarcity and inter-communal tension.[12] It notes that the combination of climate impacts and conflict exacerbates vulnerabilities and encourages negative coping mechanisms, underscoring critical linkages between these complex policy areas.[13]

However, diplomacy creates important frameworks that, through interaction with multi-level stakeholders, can inform and implement policy. The Security Council is increasingly focused on addressing the climate-security nexus in the Lake Chad Basin. In December 2024, the Informal Expert Group on Climate, Peace, and Security (IEG) of the UNSC conducted a mission to assess the localized impacts of climate change on peace and security in North-East of Nigeria. The purpose of the mission was to understand the on-the-ground realities of climate, peace, and security in the context of the Lake Chad Basin. The delegation was accompanied by UNOWAS and received briefings from the Nigerian federal government, the Lake Chad Basin Commission (LCBC), ECOWAS, and civil society organizations, demonstrating multi-stakeholder involvement at various levels.[14]

However, while the recognition of the climate crisis as a conflict factor represents progress, UN strategies fail to fully appreciate the nuances of local adaptation and mitigation initiatives and their potential to transform conflict. While acknowledging the importance of climate security at the international level is crucial, it is unlikely to have a meaningful impact without active stakeholder involvement.

World Bank

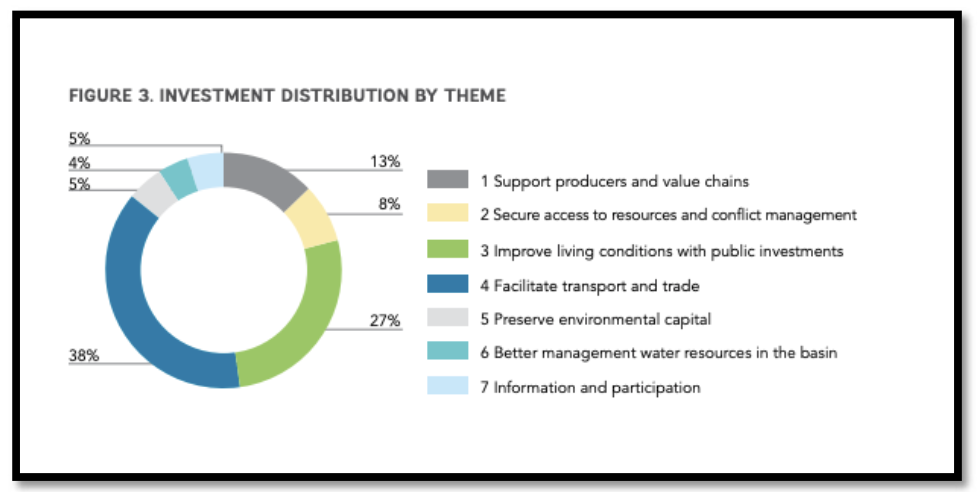

The World Bank takes a more mixed approach in its strategy and programming. Over the past five years, the World Bank Group has released several relevant documents, including program assessments and strategies. Notably, the World Bank supported the Lake Chad Basin Commission (LCBC) in developing the Lake Chad Development and Climate Resilience Action Plan (LCDAP) for 2016-2025. The core idea of this plan is to focus on rural development alongside peace and security. It adopts a more socioeconomic, local approach and “intends to contribute significantly to food security, employment, and the social inclusion of youth by improving, in a sustainable way: (a) the living conditions of populations settled on the Lake’s banks and islands, and (b) the resilience of a system characterized by strong demographic growth, high hydrological variability, and climate uncertainty.”[15] Supporting producers is the first priority, with 13% of the dedicated resources allocated to this area.[16]

In general, the World Bank tends to adopt a more bottom-up approach compared to the more top-down orientation of the UN. For example, recognizing the intersectionality of fragility, conflict, and violence (FCV) with climate-related risks, the Bank developed a “Participatory Local Development” tool to identify and address climate security challenges in the Lake Chad Basin and Guinea. This tool aims to empower local communities and institutions to better understand the interconnections between climate, disaster, and FCV risks, support marginalized groups, involve communities in decision-making, and enable responsive, agency-driven planning.[17]

The World Bank’s Western & Central Africa Region (AFW) Priorities 2021-2025 focus on four overarching goals, with the fourth being to scale up climate resilience.[18] A 2022 operational brief on Climate Change and the Blue Economy in Africa outlines the World Bank’s climate strategy on the continent,[19] building on the World Bank Group’s Climate Change Action Plan (2021–2025) and its commitment to accelerating climate action:

- “Increasing World Bank Group investments: US$10 billion of World Bank and International Finance Corporation funding will be used for climate-smart projects and policy reforms, leveraging an additional US$2 billion in private sector financing.

- Balancing adaptation and mitigation: Fifty percent of climate finance will be invested in initiatives that help build resilience, guided by regional and country-specific demand.

- Integrating climate risk management: Strategies and interventions will be informed by the World Bank’s country climate and development reports, a core diagnostic tool that helps identify country-level risks and opportunities linked to low-carbon growth.”

Additionally, a 2025 report by World Resources Institute (WRI) and the World Bank provides a comprehensive assessment of climate resilience and nature-based solutions (NBS) in Sub-Saharan Africa. The report analyzes nearly 300 projects over the past decade, highlighting a 15% annual growth between 2012 and 2021, with total financing reaching $21 billion from multilateral development banks, international donors, and national budgets. Most NBS projects pursue multiple climate objectives, create jobs, and support biodiversity conservation—demonstrating strong potential to influence broader policy and strategy.

While the World Bank’s financial contributions are significant, investment needs remain high.[20] The growing emphasis on climate investment, agriculture, and participatory local development is encouraging; however, not all local climate solutions require massive funding. Many depend instead on improved knowledge sharing and strengthened governance structures.

The European Union

The European Union (EU) has been a key partner in supporting Africa’s green transition, including through collaboration with the African Union. The Global Gateway Africa—Europe Investment Package aims to accelerate Africa’s green transition, promote sustainable growth, and foster decent job creation. Under this initiative, €150 billion in investments—mobilized by the EU, its Member States, and European financial institutions—has been earmarked for a wide range of projects, including green infrastructure and NBS projects in West Africa. Furthermore, the EU and AU jointly fund research and innovation initiatives focused on food and nutrition security, sustainable agriculture, and renewable energy.[21]

The EU Green Deal and associated climate strategy (COM(2021) 82) “promote sub-national, national and regional approaches to adaptation, with a specific focus on adaptation in Africa, Small Island Developing States (SIDS), and Least Developed Countries (LDCs).” One of the key pillars of the EU-Africa Strategy is the partnership for green transition and energy access, which complements the Africa-EU Energy Partnership (AEEP) and the Africa-EU Renewable Energy Cooperation Programme (RECP).[22]

However, despite these political and financial commitments, Africa is notably absent from the European Commission’s 2025 Work Programme. Whether these initiatives translate into societal benefits—or remain largely advantageous to businesses—depends as much on local transparency as it does on effective European oversight.

What holds greater geopolitical weight in West Africa today are the enduring postcolonial ties between European countries and the continent. In January 2025, France took another step back from its military presence in the Sahel, handing over its base to Chadian authorities following Chad’s announcement to terminate its security and defense agreements with France. This marks a continuation of the troop withdrawal process that began in 2022, prompted by growing public opposition to French military presence and the limited effectiveness of Operation Barkhane, France’s counterterrorism mission in the region. As of now, France has been pushed out of Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Chad, with Côte d’Ivoire and Senegal signaling similar plans for 2025.[23] Several factors underlie this strategic shift: the perception of continued neocolonialism through military presence, dissatisfaction with ineffective anti-terrorism amid persistent insecurity, and a broader geopolitical realignment of African states towards emerging powers such as China and Russia.[24]

In this evolving landscape, hard security priorities often overshadow climate action, both in funding and political focus. The recent emphasis on rearmament and militarization across European channels significant resources toward defense, standing in stark contrast to previous struggles to mobilize adequate financing for climate adaptation and mitigation. However, the ongoing decolonialization of security may open space for a new geopolitical dynamic in West Africa—on one side, increased competition among global powers such as China and Russia, and on the other, the potential for grassroots, bottom-up security initiatives that are more attuned to local climate vulnerabilities.

OECD

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) plays a marginal role in policymaking but offers valuable evaluations. It hosts the Secretariat of the Sahel and West Africa Club (SWAC), whose mission is to promote regional policies that enhance the economic and social well-being of populations in the Sahel and West Africa. To that end, SWAC provides data collection, policy analysis, and support services, with a focus on food systems, urbanization and territorial dynamics, and security.[25]

Primarily fulfilling an analytical rather than directive role, the OECD published a report ahead of the 2022 COP analyzing the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) under the Paris Agreement for 17 West African countries. The report found that while the NDCs are ambitious, their implementation is unlikely without improved access to climate finance and greater transparency. The findings underscore the region’s significant capacity-building needs and the importance of better vertical integration of sub-national actors into national climate strategies to unlock the transformative potential of climate action.[26]

Africa

Most importantly, African actors are shaping their own responses to climate-related challenges. The African Union Climate Change and Resilient Development Strategy and Action Plan (2022-2032) envisions a sustainable, prosperous, equitable and climate-resilient Africa.[27] With the overarching objective of enhancing the resilience of African communities, ecosystems, and economies—and supporting regional adaptation—the strategy provides a continental framework for collective action and enhanced cooperation. It aims to improve livelihoods and well-being, enhance adaptation capacity, and foster low-emission, sustainable economic growth through:

1- Strengthening the adaptive capacity of affected communities and managing climate-related risks.

2- Pursuing equitable and transformative low emission, climate-resilient development pathways.

3- Enhancing Africa’s capacity to mobilize resources and improve access to and development of technology for ambitious climate action.

4- Promoting inclusion, alignment, cooperation, and ownership of climate strategies, policies, programmes and plans across all spheres of government and stakeholder groupings.

Drawing on the UNFCCC Climate Action Pathways and African countries’ commitments under the 2015 UNFCCC Paris Agreement, the Strategy identifies eight cross-sectoral opportunities essential for achieving climate-resilient development pathways and advancing the SDGs. All are key to establishing secure, sovereign, diversified food systems:

1- Transforming food systems

2- Protecting land-based ecosystems

3- Transforming energy systems

4- Transforming mobility and transport

5- Enhancing inclusive, low-emission industrialization

6- Transforming water systems

7- Developing the blue economy

8- Driving digital transformation

9- Building resilient urban centers

Crucially, the ECOWAS Regional Climate Strategy (RCS) and Action plan (2022-2030) aims to contribute to the implementation of the AU strategy by promoting green and resilient growth and by strengthening the adaptive capacities of African economies, societies, and ecosystems. Specific objectives include capacity-building to anticipate and manage current and future climate risks—particularly biophysical, socio-economic, macro-economic, and gender-related vulnerabilities.

The strategy also supports the implementation of policies and actions to address climate change, notably through education, gender mainstreaming, entrepreneurship, innovation, and support for research and technological development. These efforts aim to seize economic opportunities and develop future-oriented sectors, such as the blue and green economy. Moreover, the strategy emphasizes strengthening cooperation and solidarity among Member States, particularly through mechanisms for coordinated and urgent responses to climate impacts. Additionally, ECOWAS’ 2050 Vision positions the fight against climate change as a key catalyst for achieving its long-term goals.[28]

Ambitions are both holistic and targeted, reflecting a growing recognition of the critical importance of climate resilience in the region. However, ECOWAS remains politically fragmented at key moments of collaboration. For example; the inconsistent implementation of the Protocol on Transhumance generates confusion and tension around the free movement of persons, goods, and services—directly impacting the mobility of herders. Without clarity on mobility, pastoralism and seasonal herding cannot fulfill their potential as adaptive, resilient, and productive livelihoods.

Conclusion

West-Africa does not need more high-level strategies on climate and food security. Climate has rightfully become central to strategic priorities, but action continues to lag behind rhetoric. What this highly vulnerable region requires is not more vision, but granular implementation and locally grounded action. The growing number of ambitious action plans starkly contrasts with limited crisis response capabilities and the intensification of conflict and climate-related disasters on the ground.

There is an urgent need for more context-sensitive research to identify locally adapted best practices that can translate political ambitions into tangible benefits for communities. Many of the current initiatives overlook the complex dynamics of climate impacts on resource governance and fail to interrogate the political structures that inhibit innovative resilience.

Local, regional, and national leaders must adopt a holistic understanding of climate, environmental, and food system challenges—rooted in the sociocultural and economic realities of the region. This includes recognizing resource management systems based on solidarity, tradition, and regenerative principles, which hold the potential to reinforce climate resilience, food security, and the broader socioeconomic well-being of communities.

[1] For instance, seasonal transhumance has proven to be one of the most resilient livelihood systems, with the added benefit of contributing to the regreening of desertified areas by integrating livestock into dryland ecosystems.

[2] Rida Lyammouri and Boglarka Bozsogi, “Floods in the Lake Chad Basin and the Sahel: The Climate Change-Conflict Nexus,” January 10, 2025, https://www.policycenter.ma/publications/floods-lake-chad-basin-and-sahel-climate-change-conflict-nexus

[3] Rida Lyammouri and Boglarka Bozsogi, “Floods in the Lake Chad Basin: The Climate-Displacement Nexus,” 20 November 2024, https://www.policycenter.ma/publications/floods-lake-chad-basin-climate-displacement-nexus

[4] Rida Lyammouri and Boglarka Bozsogi, “Flooding and Climate Shocks: Their Effect on Local Economies in the Lake Chad Basin,” December 6, 2024, https://www.policycenter.ma/publications/flooding-and-climate-shocks-their-effect-local-economies-lake-chad-basin

[5] Rida Lyammouri and Boglarka Bozsogi, “Floods in the Lake Chad Basin and the Sahel: The Climate Change-Conflict Nexus,” January 10, 2025, https://www.policycenter.ma/publications/floods-lake-chad-basin-and-sahel-climate-change-conflict-nexus

[6] United Nations, “UN Security Council Informal Group visits Nigeria, addresses Climate, Peace, and Security Challenges in Lake Chad basin,” December 12,2024,https://nigeria.un.org/en/285744-un-security-council-informal-group-visits-nigeria-addresses-climate-peace-and-security

[7] Olowoyeye, O.S.; Kanwar, R.S. Water and Food Sustainability in the Riparian Countries of Lake Chad in Africa. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10009. https://doi.org/10.3390/ su151310009

[8] “United Nations Office for West Africa and the Sahel,” Accessed March 2025, https://unowas.unmissions.org/

[9] “Political and Peacebuilding Affairs,” Accessed March 2025, https://dppa.un.org/en

[10] UNOWAS, “Regional Conference on Climate Change, Peace and Security in West Africa and the Sahel,” April 4, 2022, https://unowas.unmissions.org/regional-conference-climate-change-peace-and-security-west-africa-and-sahel

[11] UNSC, “Report of the Secretary-General on the Situation in the Sahel Region,” June 14, 2013, https://docs.un.org/en/S/2013/354

[12] “The regional climate trends observed over the past 40 years in the Sahel show that the impact of changing climatic conditions on the availability of natural resources (land and water), coupled with other magnifying factors, has led to increased competition over natural resources and tensions between communities. While migration and the movement of people and livestock are an integral part of the ancestral livelihood strategies of the Sahel, they also occur as a result of multiple climate and market shocks.”

[13] “In particular, many families and communities do not have the capacity to safely and appropriately withstand the damaging effects of climate, poor results in the agro-pastoral sector, market fluctuations and other socioeconomic shocks facing them. Conflict further exacerbates existing vulnerabilities. The adoption of negative coping mechanisms, such as selling valuable assets, including agricultural inputs and livestock, incurring debt, migrating to urban areas, withdrawing children from school and reducing the quantity and nutritional quality of purchased food leads to a vicious downward spiral of diminished coping capacity, hunger, poverty and destitution. Poverty and destitution are also among the underlying reasons why children from the region are associated with armed groups, as demonstrated by reports of cross-border recruitment of children from Burkina Faso and Niger by armed groups operating in Mali.”

[14] United Nations, “UN Security Council Informal Group visits Nigeria, addresses Climate, Peace, and Security Challenges in Lake Chad basin,” December 12, 2024,https://nigeria.un.org/en/285744-un-security-council-informal-group-visits-nigeria-addresses-climate-peace-and-security

[15] World Bank, “The Lake Chad Development and Climate Resilience Action Plan,” Accessed March 2025, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/365391467995401917/pdf/Summary.pdf

[16] Ibid.

[17] Johanna Demboaek, Koari Oshima, Corey Pattison, and Nicolas Perrin, “Building resilient communities in West Africa in the face of climate-security risks,” November 11, 2020, https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/dev4peace/building-resilient-communities-west-africa-face-climate-security-risks

[18] World Bank, “Supporting a Resilient Recovery: The World Bank’s Western and Central Africa Region Priorities 2021-2025,” Accessed March 2025, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/978911621917765713/pdf/Supporting-A-Resilient-Recovery-The-World-Bank-s-Western-and-Central-Africa-Region-Priorities-2021-2025.pdf

[19] World Bank, “Climate Change and the Blue Economy in Africa,” 2022, accessed March 2025,https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/4659697df287ba5e0dcfcf41efdb3f8a-0320012022/original/Climate-Change-and-the-Blue-Economy-in-Africa.pdf

[20] World Resources Institute, “Growing Resilience: Unlocking the Potential of Nature-Based Solutions for Climate Resilience in Sub-Saharan Africa,” February 19, 2025, https://www.wri.org/research/nbs-climate-resilience-sub-saharan-africa

[21] European Commission, Global Gateway, accessed April 2025, https://international-partnerships.ec.europa.eu/policies/global-gateway_en

[22] South African Institute of International Affairs, “Partnership for a green transition and energy access: Strategic priorities for Africa and Europe,” September 29, 2020,https://saiia.org.za/research/partnership-for-a-green-transition-and-energy-access-strategic-priorities-for-africa-and-europe/

[23] Sarah N'tsia, “A weakened France bids Africa adieu,” Euractive, February 5, 2025,https://www.euractiv.com/section/defence/news/france-loses-ground-on-the-african-front/

[24] Robert Lansing Institute, “French Troop Withdrawals and Africa’s Geopolitical Realignment,” January 3, 2025,https://lansinginstitute.org/2025/01/03/french-troop-withdrawals-and-africas-geopolitical-realignment/

[25] OECD, Sahel and West Africa Club, accessed April 2025,www.oecd.org/swac

[26] OECD, West Africa and the global climate agenda, accessed April 2025,https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/west-africa-and-the-global-climate-agenda_e006df00-en.html

[27] African Union, “Climate Change and Resilient Development Strategy and Action Plan (2022-2032),” February 10, 2023,https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/41959-doc-CC_Strategy_and_Action_Plan_2022-2032_08_02_23_Single_Print_Ready.pdf

[28] ECOWAS,“Regional Climate Strategy (RCS) And Action plan (2022-2030),” April 2022, https://ecowap.ecowas.int/media/ecowap/file_document/2022_ECOWAS_Regional_Climate_Strategy_and_Action_Plan_2022-2030_EN.pdf