Publications /

Policy Brief

The evolving structure of international power—from the erosion of unipolarity to the emergence of multipolarity (though still susceptible to a scenario where multipolarity evolves into a new form of bipolarity)—is giving rise to various material and ideological factors that are steering global dynamics toward a new ‘regionalization of globalization’. The real opportunity lies in not just considering a new form of regionalism, but in focusing on the potential of a new kind of region: the Atlantic Basin. This would represent a new type of regionalism—not merely trans-oceanic, but an ocean basin region. It envisions a space for pan-Atlantic cooperation and peace, and an ongoing process of Atlantic Basin region-building through the gradual development of a multilayered web of cooperation across various spheres.

Introduction

Recap

In the previous policy brief (Number 5, “Liberalism and Pan-Atlanticism (I): Realism versus Liberalism in the Atlantic Basin”) in this ongoing series, Pan-Atlanticism: The Atlantic Basin in a Multipolar-Transnational World, we established the foundation for a more in-depth analysis of pan-Atlantic cooperation, pan-Atlanticism and Atlantic Basin regionalism from a liberal perspective. We began by delving deeper into realism, then compared it with liberalism to examine how both relate to the evolving structure of international power and their respective stances on a key feature of contemporary globalization—the spread of asymmetric interdependencies.

This previous brief also sought to highlight:

- Why liberalism typically aspires to universal global jurisdiction and global governance, in sharp contrast with realism.[1]

- Why the most ambitions forms of liberalism thrive during periods of unipolar hegemony, such as neoliberalism in economics and progressive liberal internationalism in international relations.

- Why liberalism adopts a more ‘pragmatic’ approach under other potential structures of international power (multipolarity, bipolarity), scaling back its push for universal global jurisdiction and embracing regionalism instead.

- How the shortcomings and failures of liberalism, particularly progressive liberal internationalism, have contributed to undermining the liberal international order and hastening its potential collapse.

- Why the global economic fragmentation, partly triggered by these failures, may lead liberals—along with realists—to reconsider regionalism as a strategic alternative.

Roadmap

The aim of this brief is to provide more historical and analytical depth to the conceptual comparison of realism and liberalism regarding the evolution of international power structures and the widespread contemporary asymmetric interdependencies explored in the previous brief. Additionally, we will link this discussion to an analysis of the relationship between regionalism and the global jurisdiction of multilateral institutions within the liberal international order. A central thesis of this brief is that the evolving structure of international power—from the erosion of unipolarity to the emergence of multipolarity (though still susceptible to a scenario where multipolarity gives way to a new form of bipolarity)—is giving rise to various material and ideological factors that are steering global dynamics toward a new ‘regionalization of globalization’.

In doing so, we will further explore:

- The relationship between liberalism and regionalism over three ‘generations’ of regionalism.

- The impact of the erosion of the multilateral trade order on recent regionalism trends.

- The potential consequences of economic regionalism for the liberal objectives, such as global free trade, the strengthening of the multilateral trade regime, and rising global prosperity.

- The growing incentives for a new economic regionalism driven by deepening multipolarity, intensified geostrategic competition, and the resulting economic fragmentation and strategic realignment.

- The innovative forms recent regionalisms have taken, and the new liberal possibilities that may emerge, including pan-Atlantic cooperation and Atlantic Basin regionalism.

The real opportunity lies in not just considering a new form of regionalism, but in focusing on the potential of a new region: the Atlantic Basin. This would represent a new type of regionalism—not merely trans-oceanic, but an ocean basin region. It envisions a space for pan-Atlantic cooperation and peace, and an ongoing process of Atlantic Basin region-building through the gradual development of a multilayered web of cooperation across various spheres.

Liberalism and Regionalism

The concept of economic regionalism may initially seem at odds with the traditional liberal view of the international order, as embodied in the multilateral institutions of the UN-Bretton Woods global governance system. As outlined in the previous brief, the liberal free trade perspective seeks a single global jurisdiction. Any form of regionalism, particularly an ocean basin regionalism, would appear—at least at first glance—contrary to this liberal preference. Historically, liberal economists would have viewed a new regional arrangement within the global multilateral trade regime (already entangled in a ‘spaghetti bowl’ of bilateral and regional trade agreements) as an unnecessary distraction and distortion, likely to lead to sub-optimal outcomes.[2]

There is, however, an inherent tension within liberalism, particularly liberal internationalism, between its preference for global reach—driven by economies of scale and economic efficiencies—and a more pragmatic geostrategic regionalism, which acknowledges realism and geostrategic competition.[3] This tension suggests that, under the right circumstances, liberals, much like realists, could easily embrace pan-Atlantic cooperation in specific contexts and potentially even support an Atlantic Basin regionalism—which stands as one of our central theses.

Despite its inherent tendency toward globalism, liberalism has historically shown a pragmatic flexibility in adopting various regional forms of liberal multilateralism during periods of geostrategic competition and diverging global interests and values. During such times, liberals adopt a pragmatic approach: recognizing that the perfect can be the enemy of the good, they see the necessity of crafting a ‘second best’ solution. This liberal second-best pragmatism involves sacrificing the theoretical ideal of a universal global economic jurisdiction to achieve some of the benefits of international economic integration—such as scale, efficiency, growth, prosperity, security and peace—even if those gains are confined to a more limited regional market or cooperative framework.[4]

However, pragmatic liberalism sometimes retains an optimism and even a progressive activism regarding the long-term prospects of universal global jurisdiction within the multilateral trading system. While accepting the need to sacrifice global jurisdiction in the short-to-medium term, some progressive liberal internationalists view regional trade agreements as ‘stepping-stones’ towards a superior global multilateral regime in the long run. In these cases, regional agreements are seen as ‘second-best’ solutions only provisionally, with the potential to act as accelerators for future progress towards further liberalization of global economic relationships.

Similarly, just as realists have utilized economic regionalism as a tool for geostrategic competition—such as the successful European Coal and Steel Community, which helped contain the USSR, or the US’s orphaned Trans-Pacific Partnership, which was part of the ‘pivot to Asia’ in the second Obama administration—pragmatic liberalism can and has also resorted to regionalism.

Post-WWII ‘First Generation Regionalism’

Following World War II, the liberal economic framework was internationalized with the establishment of the Bretton Woods institutions. The original liberal economic models developed in the United Kingdom and the United States were extended beyond their national borders to encompass much of the First World, albeit with some mixed-economy modifications in Europe. Over time, this liberal framework also began to include much of the Third World, where protectionist import-substitution industrialization models—such as in Brazil—were often tolerated by liberals, particularly within the context of Cold War strategic competition.

In line with George Kennen’s strategic advice to follow a long-term policy of ‘containment’ of the Soviet Union[5] —rather than opting for short-term invasion or forced regime change—US foreign policymakers and strategists viewed a recovered, prosperous and liberal Europe as both an ideological bastion of resistance against communism and a strategic hard power bulwark along the key Eurasian rimland. This was seen as essential to counter the perceived aggressive strategy of the Heartland regime (the USSR) to dominate the supercontinent. Simultaneously, liberals saw the prospect of a united and integrated Europe as an opportunity to implant liberal market economics and rules-based ‘free trade’ across the Northern Atlantic world, extending to Japan and Australia.

The Marshall Plan itself, the OEEC (later the OECD) and the European Coal and Steel Community (which later became the EC) were all key elements of a US strategy to enable Europe’s reconstruction and accelerate its growth through closer trade integration. The US imposed liberal economic conditionality on those projects while, at the same time, allowing for explicit exceptions within the original GATT framework. These exceptions permitted members of formal preferential trade agreements (PTAs) or regional free trade associations (RTA/FTAs) to bypass a central requirement of the treaty—the ‘most favored nation’ (MFN) clause, which requires that the most favorable trade terms offered to any one country must be extended to all countries in the agreement.

The GATT’s MFN waiver allows members of PTAs, RTAs, or FTAs[6] to grant each other more favorable tariff treatment than they extend to other MFN beneficiaries within the broader multilateral agreement. Preferential trade conditions among regional partners are intended to foster growth and stimulate new ‘intra-regional trade’, thereby binding these countries more closely together through deepening interdependencies. This early Western European integration exemplified the ‘first generation’ of regionalisms that emerged during the Cold War.

The creation of an increasingly integrated Europe aligned with US strategy, bolstering European allies in the Cold War rivalry against the Soviet Union—a top priority for realists—while NATO established the Northern Atlantic security regime. This represents a clear convergence of geostrategic realists’ interests and pragmatic liberals’ ideals during the Cold War. Similarly, US support for ASEAN has followed a comparable logic, blending realists’ security concerns (seeing Southeast Asia as another key rimland to influence) with liberals’ economic and political perspectives. For liberals, ASEAN represents a ‘second best’ option to a global agreement and, in the long term, a potential building block or stepping stone towards a future global liberal international order.[7]

Nevertheless, the reach of the early Bretton Woods system remained limited to the non-communist world. The strategic and ideological competition of the Cold War, shaped by the bipolar international balance of power and the counterweight of the Warsaw Pact and COMECON, kept liberal internationalism largely contained within the West. However, in the years following Gorbachev’s perestroika and glasnost policies—with the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Velvet Revolutions in Eastern Europe, and the dissolution of the USSR—most states in the Second and Third Worlds, particularly in Eurasia and the Southern Atlantic, embarked on a dual transition to market-based economies and open, multiparty democratic systems, albeit with varying levels of enthusiasm.

During the unipolar moment that followed the Cold War, liberals argued that a single, free—but regulated and arbitrated—global economy would be far more efficient, productive, and innovative than the sum of its parts, such as individual national economies operating as partially free markets or mixed economies. They posited, and increasingly assumed, that the values of liberty and freedom in economic life—within the fair play constraints of a rules-based regime—were ‘universal’, much like the notion of human rights was declared universal under the United Nations nearly half a century earlier. The clear objective of the liberal international order, under US unipolar hegemony, was to establish a consolidated global economy based on free trade and multilateral governance. For liberals, this model was not only the most effective framework for fostering global economic development and prosperity, particularly in the developing world and emerging markets, but also for reducing international conflict and minimizing the risk of war among major powers.

In the end, the collapse of most socialist planned economies and communist political systems left the liberal international institutions of the ‘Free World’ unrestrained. The wave of market transitions across the former Second and Third Worlds enabled liberalism to finally achieve its long-sought universal global jurisdiction. The IMF, the World Bank and, later, the World Trade Organization (established in 1994) were now free to operate across nearly the entire global economy, fully embracing it within their frameworks.

Post-Cold War ‘Second Generation Regionalism’

As the Cold War ended, many newly emerging ‘market democracies’ began integrating more fully into the rapidly globalizing economy. Most joined the Bretton Woods institutions (if they had not already), including the newly formed WTO. These transitioning and emerging market economies were subsequently guided—and constrained—by the dictates and disciplines of the Washington Consensus, which, through the practices of the IMF and the World Bank, spread its influence across the world, deepening over the next two decades.

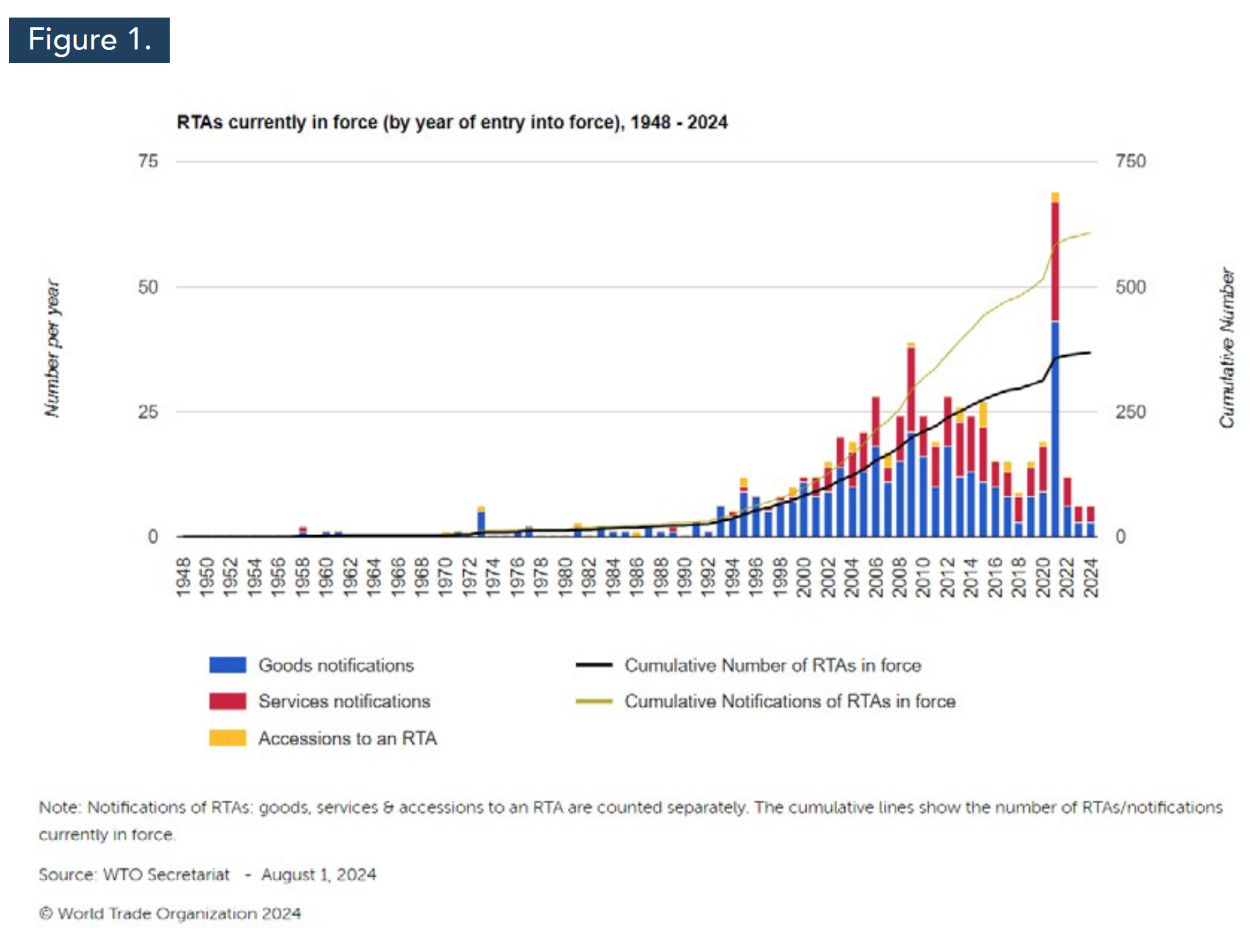

Paradoxically, just as liberalism’s aspiration for universal global jurisdiction began to materialize—with the liberal international order expanding globally under US unipolar hegemony—hundreds of new PTAs, FTAs and other forms of economic regionalism emerged across the world.[8] As noted by Uri Dadush and Enzo Dominguez Prost, “a sharp acceleration in the number of agreements notified to the WTO occurred around 1991, shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the entry of formerly planned economies into the mainstream of world trade”.[9] Prior to 1992, fewer than 10 RTAs/PTAs existed; by 2010, there were over 300 in force.[10] By that time, more than 60% of global trade was conducted under some form of preferential agreement.[11] Notably, two-thirds of these agreements were between or among developing countries, including the majority of nations undergoing market transitions.[12]

The new regionalisms emerging from this post-Cold War surge included agreements like the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the Southern Common Market (Mercosur), the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and the European Union (EU)—to name just a few emblematic cases from each of the Atlantic continents.[13] However, the motives and driving factors behind this ‘second generation’ of RTAs were diverse, evolving over time, and often ambiguous or even contradictory.

Initially, economic liberalism was the dominant driving force behind this wave of regionalism.[14] This was particularly evident in the creation of NAFTA and the EU, along with its subsequent Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) and the expansion to include the transition economies of Eastern Europe. Many of these second-generation agreements were eventually registered with the new WTO as regional free trade areas (or, in some cases, as deeper forms of regionalism like customs unions or economic and monetary unions). As with Europe during the first generation of regionalism, the RTA exemption from the MFN clause allowed countries to broaden and deepen economic integration with their regional neighbors more rapidly than would have been feasible through the multilateral route.[15] In transition and emerging markets, the hope was that such regional integration would help bolster and stabilize market reforms,[16] especially by enabling faster export growth and economic expansion than could be achieved by relying solely on WTO MFN status—or while waiting to be accepted as WTO members.

At the time, political and economic liberalism were either in ascendency or gaining momentum in most transition and emerging market economies. Reducing trade barriers, particularly tariffs, became a standard component of the market transition reforms required to satisfy the Washington Consensus, as outlined by the IMF and World Bank, and to facilitate WTO membership, which granted access to MFN status and equal national treatment within the multilateral regime. Market reforms, trade liberalization, WTO membership and legitimate regional trade agreements appeared to align, at least superficially, within a simplistic liberal worldview. This worldview was increasingly embraced—sometimes enthusiastically, sometimes reluctantly—in most transition, emerging and developing economies during the unipolar moment.[17] At that time, the potential contradiction between regionalism and the liberal international order was not immediately apparent to most observers.

In the new unipolar world dominated by the US version of liberalism, there was a certain degree of ‘band-wagoning’ in the promotion and proliferation of RTAs. This mirrored the decisions of non-market economies at the end of the Cold War to transition to market-based systems, as well as the behavior of most global economic actors, who perceived the high opportunity costs of not aligning with the liberal international order. RTAs gained legitimacy and were even encouraged by the fact that Northern Atlantic countries themselves were either creating (NAFTA) or deepening (the EU) their own economic regionalisms—precisely as the WTO was being negotiated and launched.

Progressive liberal internationalists shaping US trade policy actually promoted RTAs globally, viewing them as stepping stones toward the eventual consolidation of the universal jurisdiction of the multilateral trade regime. They believed these agreements would accelerate further and deeper liberalization of the global economy. In practice, RTAs were often used as geoeconomic levers by the Northern Atlantic powers, particularly the US and Europe, to pressure reluctant WTO partners to move faster on multilateral agreements. These partners were often hesitant to commit to deeper liberalization, especially in ‘behind-the-border’ areas that could challenge national sovereignty, even though such reforms had the potential to drive positive national transformation in the long run.

RTAs in the non-Western world were soon affected by the negative economic shocks of recurring emerging market crises during the 1990s and early 2000s. The IMF and World Bank often responded with their controversial austerity policies and structural adjustment requirements for financial support. Meanwhile, the Washington Consensus’s “one-size-fits-all” approach revealed a significant oversight: the lack of attention to the pacing and sequencing of reforms. It failed to account for the need to balance macroeconomic stabilization with the liberalization of prices, trade barriers, and capital flows, alongside privatization of state firms and the creation of market and regulatory institutions, all within the unique historical and material contexts of individual countries. The dominant progressive liberalism of the time also tended to downplay the sensitive relationship between the dual economic and political transitions most countries faced. This was evident in the contrasting experiences of the Russian and Chinese transitions, highlighting the impact of sequencing economic versus political reforms.

These factors deepened and prolonged the economic depressions and collapses associated with many emerging market crises. This, in turn, fostered fresh skepticism toward the original Bretton Woods institutions—whose governing boards, voting rights, and policies continue to be predominantly controlled by the West, particularly the US—planting the seeds for future critiques of the liberal international order and efforts to reform or transform it.

As the 1990s transitioned into the 2000s, economic regionalisms adopted more defensive, competitive, and strategic motivations and postures. RTAs became central to debates on national and regional strategies for optimal integration into the globalizing international economy, as well as to the accompanying geopolitical discussions (including debates over unilateral US intervention). RTAs began to represent diversity in economic arrangements, addressing the realist imperative of security, as the emerging multipolar order took shape and major emerging market powers began cooperating among themselves (e.g., the SCO and the original BRICs).

In this context, RTAs were seen as a response to the suspicion that the EU and NAFTA might ultimately prove protectionist in their global impact as blocks. RTAs offered countries additional strategic leverage through their membership in larger economic groups. They could help counteract the marginalization of emerging and transition economies within the global system and provide some cushion against international financial and economic instability, including financial contagion (particularly if they progressed toward monetary union, as seen with ASEAN beginning in the 2000s). The right kind of South-South regionalism could, in theory, moderate and partially offset the economic and political influence of the Northern Atlantic.

Regardless of the evolving motives and shifting postures of second-generation regionalisms, the proliferation of RTAs introduced overlapping rules and additional requirements that complicated trade. This complexity diluted the effectiveness of the multilateral trade regime, increasing the likelihood of disputes, and raised transactions costs. The resulting uncertainty over the WTO’s future became a motivating force behind the continued proliferation of RTAs.

By the end of the 1990s, efforts to deepen global integration through the WTO (which requires unanimity) had become mired in gridlock, driven by competing interests between Europe and the US on one side, and between the Northern Atlantic and various emerging markets on the other. The WTO’s 1999 Ministerial Meeting intended to launch the Millennial Round—its first formal round of multilateral trade negotiations—was overshadowed by the ‘Battle of Seattle’ protests by a diverse coalition of ‘anti-globalization’ activists. However, the talks themselves collapsed early due to unresolved transatlantic and North-South divides, leading to a failure to agree on an agenda for the new round.

After the failure at Seattle, the ongoing proliferation of RTAs and the rising uncertainty in trade policy came to reinforce one another. This dynamic became especially pronounced as the Doha Round—intended to revive the WTO’s stalled multilateral trade agenda—languished for years without substantial progress. In this uncertain environment, pursuing RTAs served as a hedge against potential futures for the WTO. If the WTO continued to stagnate, or if the reliability of its rules eroded, the value of existing PTAs/RTAs would increase significantly. In such a scenario, RTAs became both a hedging strategy and a viable second-best alternative to multilateral progress.

Regional Trade Agreements: Stumbling Blocks, Stepping Stones or Second-Bests?

As noted earlier in this policy brief, classical or traditional liberals often view the proliferation of RTAs as a ‘stumbling block’ to the consolidation of the global trade regime, rather than a catalytic stepping stone or complementary building block.[18]

Today, there are over 350 PTAs and RTAs in force, yet, collectively, they only offer about 1% relative trade advantage, on a weighted basis, over the existing multilateral MFN treatment.[19] This small marginal advantage raises questions about whether the additional resources and costs are justified. Moreover, the risks that RTAs pose to the multilateral trade regime and liberal goals more broadly exacerbate these concerns, which is why traditional liberals often express frustration over their proliferation.

This more traditional branch of liberalism tends to view regional economic accords and global economic governance as fundamentally incompatible. Regional agreements are seen as diverting attention, resources, and strategic priority away from efforts to expand and enhance the liberal multilateral trade order. Participation in such regional pacts places additional administrative burdens on already overstretched national officials and representatives, further draining the state’s skilled human resources—particularly in developing economies. According to this traditional view, the cumulative effect of regional agreements is to weaken the effectiveness of, and overall compliance with, the global multilateral trade regime.

In addition, RTAs can lead to ‘trade deflection’, particularly in shallower forms like PTAs and FTAs that do not enforce a common external tariff. This distortion arises because, in the absence of a unified external tariff, goods from outside the FTA can enter through the member country with the lowest tariff, regardless of their final destinations within the trade area. The resulting trade arbitrage effectively creates a de facto common external tariff, informally set by the member with the lowest tariff, which can undermine the intended trade policies of other member countries.

Therefore, ‘rules of origin’ (RoO) provisions, now standard in FTAs, were designed to prevent trade distortion.[20] Unfortunately, RoO administrative requirements impose additional transaction costs that diminish the trade creation effects, particularly in developing countries. In some PTAs, ‘preference utilization rates’ are as low as 66%, indicating significant untapped trade creation potential, largely hindered by the burdens of RoOs.[21] Moreover, evidence suggests that trade deflection is rarely profitable, as most tariffs are already low, tariff differences between members tend to be minor, and transportation costs typically more than outweigh any residual arbitrage profits. This renders RoOs superfluous in many cases,[22] leading to their characterization as ‘unsavory sauce’ in Bhagwati's metaphorical spaghetti bowl[23] of preferential, bilateral and regional trade agreements.

More importantly, however, liberal economists are often concerned about the possibility that trade regions might destroy as much income and welfare as they create, if not more, through a dynamic known as ‘trade diversion’. This occurs when preferential trade conditions reorganize production and exchange among partners in a way that is less efficient in global terms compared to when their economic actors were guided primarily by comparative advantage within the larger global market under the multilateral regime.

The long-standing liberal perspective, following the logic of Jacob Viner, holds that RTAs, by lowering tariffs between members, stimulate new trade within the region (trade creation). However, this preferential treatment also increases the level of trade policy discrimination faced by firms in non-member countries. As a result, members may substitute imports previously sourced from more efficient non-members with products from less efficient producers within the bloc. This process leads to a reduction in non-member exports, thereby causing trade diversion, which undermines global efficiency.[24]

The net welfare impact of any RTA is ambiguous,[25] as it depends on whether trade creation or trade diversion predominates. This is ultimately an empirical question, influenced significantly by the specific contents of the agreements. An RTA becomes protectionist if it diverts more trade from non-members than it creates among members, leading to net welfare destruction and a beggar-thy-neighbor effect similar to tariffs. Globally, this would result in an unnecessary loss of output and income that the current multilateral regime could have maintained, or that a more effective global trade order might have even expanded.[26] In such cases, an RTA becomes a barrier to the liberal goal of freer global trade and a stumbling block to consolidating the universal jurisdiction of the multilateral trade regime.

‘Deep’ Free Trade Agreements

Over time, RTAs have evolved to become deeper and broader in their reach than the earlier generations of preferential trade agreements, which focused primarily on tariffs and often lacked a common external tariff. Deeper forms of economic integration, such as customs unions (CUs), are argued by proponents to potentially divert less trade due to their common external tariff. In the case of common markets (CMs) like the European Community (EC), the integration extends further with a unified trade policy, a single market with free movement of goods, services, labor, and capital, and shared regulatory standards and acquis. Despite these advancements, less than 10% of all trade agreements signed since 1945 have been CUs, and even fewer have been CMs.[27]

Since the global financial crisis (2008-2012) and marking the emergence of a ‘third generation’ of agreements, FTAs have increasingly become ‘deeper’ without necessarily adopting a common tariff, customs union, or common market. These more recent FTAs focus on addressing ‘behind-the-border’ barriers, such as competition policy, subsidies, and regulatory standards. They also often include ‘WTO-plus’ provisions, which extend or deepen WTO rules in areas like services or intellectual property, and ‘WTO-extra’ measures, which cover issues beyond current WTO mandates, such as environmental and labor-related concerns.

Proponents of deep FTAs argue that these agreements can generate greater trade creation while minimizing trade diversion compared to shallower RTAs. Unlike preferential tariffs, the ‘behind the border’ provisions in deep FTAs are often non-discriminatory and can reduce trade costs and discrimination against outsiders. This creates a positive spillover effect, countering the potential negative impacts of trade diversion.[28] Large and deep FTAs, such as those involving the EU ‘acquis’, are seen as converting trade diversion from non-members into trade creation with them, particularly if the agreements remain ‘open’ to non-member participation and those new members adapt their domestic policy and legislation to comply with the more comprehensive and deeper rules.

Deep RTAs have the potential to create new ‘extra-regional trade’ in addition to increasing ‘intra-regional trade’, surpassing the achievements of earlier generations of shallower RTAs and even CUs. This capability allows deep RTAs to transcend the limitations of Vinerian theory, avoiding the trade diversion issues associated with shallower agreements and positioning themselves as effective stepping stones toward global free trade and greater world prosperity.[29] However, the net welfare benefits of deep RTAs remain an empirical question, influenced by the structural realities (geography and political economy) of both member and non-member countries, their responsive policies, and the specific details of the agreements themselves.

A Third Generation of Strategic and Deep Mega-Regionalisms

As the first decade of the 21st century concluded, the global financial crisis and a series of shocks began to challenge the stability of unipolar hegemony.[30] In this context, a third generation of regionalisms emerged, characterized by two potentially competitive or cooperative branches of development.

The first branch evolved from the more defensive regionalisms of the second generation, notably in Eurasia and the Southern Atlantic. These new South-South regionalisms adopted a strategic dimension, aiming to enhance their economic development and political leverage, and seeking greater autonomy and leverage with respect to the global (or regional) hegemon. In Latin America and the Caribbean, this third-generation regionalism included:

- ALBA (ALBA-TCP, the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America—Peoples’ Trade Treaty)

- CELAC (the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States)

- UNASUR (the Union of South American Nations).

These ‘post-hegemonic regionalisms’[31] adopted a competitive or oppositional stance towards a hegemon pursuing both the global jurisdiction of the multilateral trading regime (WTO) and its own regional (NAFTA) and bilateral (Chile, Peru, CAFTA-DR) preferential agreements.

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), which began taking shape in the early 2000s, also emerged in response to the competitive dynamics of globalization. It acts as a liberal counterforce in Africa against the spread of isolationism and protectionism in a strategically competitive global environment.

In Eurasia, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), originally a security-focused group but now incorporating infrastructure and economic cooperation, and the Eurasian Economic Union have been designed to enhance regional competitiveness and deepen intra-regional dependencies. These initiatives also contribute to a partial strategic decoupling from the Northern Atlantic.

Alongside Southern Atlantic regionalism (e.g., ZOPACAS) and interregionalism (e.g. ASA, the Africa-South America Summit) discussed in Policy Brief 4,[32] these agreements reflect a trend of innovative South-South third generation regionalism. This trend has culminated in initiatives such as China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and BRICS Plus.

At the same time, a second strand of third generation RTAs—those ‘deep’ agreements mentioned earlier—was promoted by the United States during the second Obama administration (2013-17), in collaboration with its Western partners in both the northern Atlantic and broad Pacific Basin. These include the initially proposed and now abandoned Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) and the former Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), which was orphaned by the subsequent US withdrawal in 2017, and is now known as the Comprehensive Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP).[33]

These ‘deep’ RTAs continue the trends of previous generations but, as noted, they go further. While tariff reductions remain on their agendas, the main focus has shifted due to already low tariff levels in the US, EU, and Asia. These agreements now emphasize improving regulatory coherence across the trade region and addressing a range of non-tariff barriers (NTBs) with new ‘behind-the-border’ rules designed to harmonize or align national policies, legislations, and standards affecting trade.

Some measures in these agreements extend or deepen WTO rules (WTO-plus), introducing new regulations on areas such as e-commerce, competition policies, financial services, state-owned enterprises, subsidies, government procurement, SMEs, intellectual property, and technical, sanitary and phytosanitary standards. They also address complex regional and global supply chains. Other measures introduce rules in areas not yet covered by the multilateral trade regime (WTO-extra), including trade-related aspects of the environment, climate change, labor, investment, food security, animal welfare, privacy standards and consumer protection.

The most ambitious goal of this generation of deep regionalism, especially from the perspective of a global hegemon facing the challenge of emerging multipolarity, was to establish a more comprehensive and enforceable rules-based trading system. This system aimed to facilitate the development of 21st-century global value chains. It sought to either complement the WTO regime—accelerating progress in liberalizing global trade—or largely supersede it in much of the world.

Unlike earlier generations of RTAs, which deepened into customs unions, single markets, and monetary unions, these deep agreements nevertheless also create a framework which serves a function to that of the EU’s acquis communitaire. In trade-related terms, this involves a matrix of harmonized or consistent national regulatory frameworks, rules, and standards affecting a broad range of goods, services, economic sectors and national policy areas across the scope of the megaregional accord.

In this context, the TTIP and TPP, as originally proposed by the US, were not only deep but also clearly megaregional and trans-oceanic, and designed by their proponents in the Northern Atlantic to be strategic. Daniel S. Hamilton of the Center for Transatlantic Relations (JHU-SAIS) highlighted this at the height of the TTIP negotiations in 2014, stating, “As Europe’s own history has demonstrated, economic integration can usefully serve as the leading edge of political cooperation”. A transatlantic pact that offers a benchmark for global standards can also spur other trade groupings to advance liberalization. Such “competitive regionalism” was a factor in the 1990s as trade groupings from Europe, South America, North America, and the Asia-Pacific all made significant steps forward. With global liberalization stalled for the foreseeable future, regional pacts may well again play a vanguard role”.[34]

If the TTIP and TPP had been as successful as originally envisioned, the US and its partners in the Northern Atlantic Plus would have achieved substantial liberalization of trade and investment across both the Northern Atlantic and much of the Pacific Basin. As the only party initially involved in both negotiations, this gave the US “a distinct advantage in leveraging issues in one forum to advance its interests in the other, while potentially reinvigorating U.S. global leadership”.[35]

Deep RTAs like the TTIP and the TPP could, however, create uncertainty for other trade partners. First, the rules they establish could potentially be incompatible with the WTO, as they might selectively include and exclude aspects of WTO regulations within these preferential treatment schemes. Given the economic weight of the members involved, these megaregional agreements could exert significant gravitational effects on international trade, potentially causing notable trade diversion or compelling non-members to undertake substantial domestic reforms. To continue trading with members of these blocs, non-members might need to align their economic models and legislation with the new set of ‘behind-the-border’, WTO-plus, and WTO-extra rules, which are likely to apply to all goods and services traded within the territories of the member countries, regardless of their origin.[36]

While the fate of the TTIP negotiations swayed in the balance, Vera Thorstensen and Lucas Ferraz analyzed the potential effects on Brazil, a key BRICS member and an essential player in any true pan-Atlantic cooperation. In 2014, they wrote “Brazilian products are likely to face technical and sanitary standards negotiated within the TTIP, or enhanced intellectual property protection in patents registered in any of the TPP partners, which may also damage Brazilian exports”. Their simulations suggested that a TTIP agreement, including full U.S.-EU tariff elimination and a 50% reduction of U.S.-EU non-tariff barriers (NTB), which they deemed the most probable outcome of a successfully concluded TTIP agreement, would reduce Brazilian exports to the US and EU by 5%, while imports from these partners would decline by 4%. They predicted that agribusiness sectors would experience GDP declines of 1%-3%, and industrial sectors would contract by 1%-2%. The trade balance would deteriorate in two-thirds of agribusiness sectors and over one-third of industrial sectors.[37]

On the other hand, had Brazil been able to participate in a successfully negotiated TTIP, it would have experienced significant gains in trade and GDP. Agriculture would have seen improvements in trade balance and GDP ranging from 3% to more than 4% in most agribusiness sectors. However, nearly all industrial sectors would have contracted by 1% to 2%, with over a third of sectors facing deteriorated trade balance, depending on the assumptions of the scenarios considered.[38]

Indeed, any pan-Atlantic trade agreement, especially one that included more countries in the Atlantic Basin beyond the US and EU, would pose a significant challenge to Brazil, particularly if it maintained its long-standing focus on the multilateral regime and did not participate. “Not only will Brazil lose international markets”, the authors wrote, “it will be left behind in the negotiations of international trade rules. It will lose its present role as relevant global rule-maker and assume a secondary role as passive rule-taker. In a time of global value chains, Brazil’s integration with these two major economies is fundamental to the survival of Brazilian industry”.[39]

In the end, the issue became moot when the Atlantic TTIP negotiations collapsed due to internal contradictions between the technological, corporate and environmental interests on both sides of the Northern Atlantic, particularly in the financial, tech and agricultural sectors, and their respective conflicting political economies. Protectionist and strategically competitive sentiments in both the US and the EU, combined with conflicts between multinational corporations and environmental interests, led to a deadlock in the negotiations by the end of Obama’s second term, before the Trump administration suspended them.

Perhaps even more tragically, the promoters and critics of the TTIP largely overlooked the missed opportunity to engage with the Southern Atlantic in a meaningful way. For instance, the agreement could have been designed to allow staged participation from other Atlantic Basin countries or used as a platform to harmonize or mutually recognize US and EU preferential trade schemes with developing and least developed countries (LDCs), especially in Africa (a possibility that remains).[40] Even pragmatic liberals failed to recognize the rising strategic significance of the Atlantic Basin—particularly the Southern Atlantic—as a coherent region. The original BRICS nations, however, began to sense this shift around that time.

The TPP, for its part, was recognized from the start as a strategic instrument of US foreign policy and a key component of President Obama’s ‘pivot to Asia’. Its geopolitical and geoeconomic nature was evident from China’s exclusion from the Pacific Basin agreement, as the de facto conditions for membership required reforms aligning national political and economic models with ‘liberal market democracy’.

The question of whether the TPP was an attempt by the US to contain a rising China or to provoke it into faster liberal reforms remains a topic of debate, especially given its abrupt and unexpected demise. Curiously, the TPP faced an early end when its major sponsor, the United States, withdrew under President Trump, despite his competitive and adversarial stance toward China.[41]

In a rational, self-interested response, China promoted its own parallel regional cooperative scheme: the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), much like the USSR once created COMECON in opposition to Bretton Woods. RCEP, which came into effect in 2023, embraced both East and Southeast Asia, including many of the TPP’s members. Initially, India was also part of the negotiations, although it has since withdrawn from the agreement.

The ‘rump TPP’ (the remaining 11 partners, without the US) continued the process, eventually signed the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) after loosening some of the rules previously insisted on by the US. However, the Biden Administration has not sought to rejoin the CPTPP. Instead, the US has pursued direct and intensifying geoeconomic competition with China, particularly in the realm of industrial and trade policy.

Paradoxically, this dynamic has set the stage for a potential de facto fusion of the RCEP and CPTPP. China applied for CPTPP membership in 2021, and if accepted—possibly with further relaxation of certain rules—China could essentially replace the US as the dominant economic force within the CPTPP’s geography. In response, the US established the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF); but unlike the CPTPP, the IPEF is not a free trade agreement or a full preference scheme, focusing instead on critical infrastructure and including only Asian and Australian members, with none from the Americas. Meanwhile, the UK applied for CPTPP membership just before China and was formally accepted in 2023, leading many to believe that China’s membership is now highly unlikely.

Continued reticence and inaction from the current US administration regarding broader Pacific Basin initiatives should serve as a clear signal to pragmatic liberals in the Atlantic world: the growing necessity of uniting the entire Atlantic Basin around a cohesive agenda of pan-Atlantic cooperation. This initiative should be pursued regardless of how it starts, even if framed with the initially shallow strategic language used to frame the recently launched Partnership for Atlantic Cooperation (PAC).

Conclusionary Remarks and Implications for the Atlantic Basin

The Structure of International Power and the Liberal Development of Regionalism

As demonstrated throughout this analysis, regionalism can emerge as a geoeconomic and geopolitical strategy—especially during periods of international rivalry and conflict. Under the Cold War’s bipolar system, the ‘first generation regionalisms’, such as the EC and Bretton Woods institutions, were liberal ‘second-best’ solutions. These were framed within a defensive realist outlook, as articulated by figures like George Kennan. They were confined to the ‘free world’ of the West (today’s Northern Atlantic Plus) due to the intense strategic competition with the socialist and communist blocs, which precluded any path toward a truly global economic cooperation framework.

During the post-Cold War unipolarity period, ‘second generation’ regional trade agreements, such as NAFTA, acted as liberal-internationalist accelerators of global trade, investment, and economic integration. These agreements complemented the newly established global jurisdiction of the WTO, aligning liberal hegemony—perhaps fatefully—with an offensive neo-con realism that dominated Northern Atlantic foreign policy at the height of the unipolar moment.

During the period of eroding unipolar hegemony and emerging multipolarity following the global financial crisis, ‘deep’ megaregional trade pacts promoted by liberals in the Northern Atlantic Plus—such as the ill-fated TTIP or the TPP—were designed to revitalize the faltering liberal international order (and with it, unipolarity hegemony). These agreements aimed to spread ‘behind-the-border’ regulations and related accords that either extended or deepened WTO rules (WTO-plus) or introduced provisions governing areas beyond current WTO mandates (WTO-extra). As such, these ‘deep’ regional trade agreements represented an effort by many progressive liberal internationalists in the Northern Atlantic to accelerate the expansion of a particular form of ‘rules-based free trade’ and to establish a ‘stepping stone’ pathway towards a more reliable and stable future trade regime—one that extended the influence of US and EU domestic regulatory frameworks, standards, and commercial rules.

In part, such behind-the-border, WTO-plus, and WTO-extra agreements were viewed by many liberals as necessary at the global level to modernize traditional multilateral trade cooperation and align it with one of the key structural features of post-Cold War globalization: the rise of extensive, intricate global supply and value chains. However, this liberal drive to maximize the efficiency of globalization also revealed a strategic alignment with an ‘offensive’ realist perspective. These ‘deep’ agreements held the potential to play a crucial role in restoring full unipolar hegemony by economically containing, through exclusion, emerging multipolar powers, particularly China, as explicitly reflected in the US ‘pivot to Asia’ strategy.

It should come as no surprise, then, that during this same period of eroding unipolarity and emerging multipolarity—when the deep megaregional agreements of the Northern Atlantic Plus were being promoted and developed—alternative branches of trade and economic regionalism also began to take shape in Eurasia-Pacific and the Southern Atlantic. These efforts culminated in the expansion of the BRICS-Plus framework, which now includes a growing number of countries in the BRICS sphere as new ‘partners’, rather than full members.

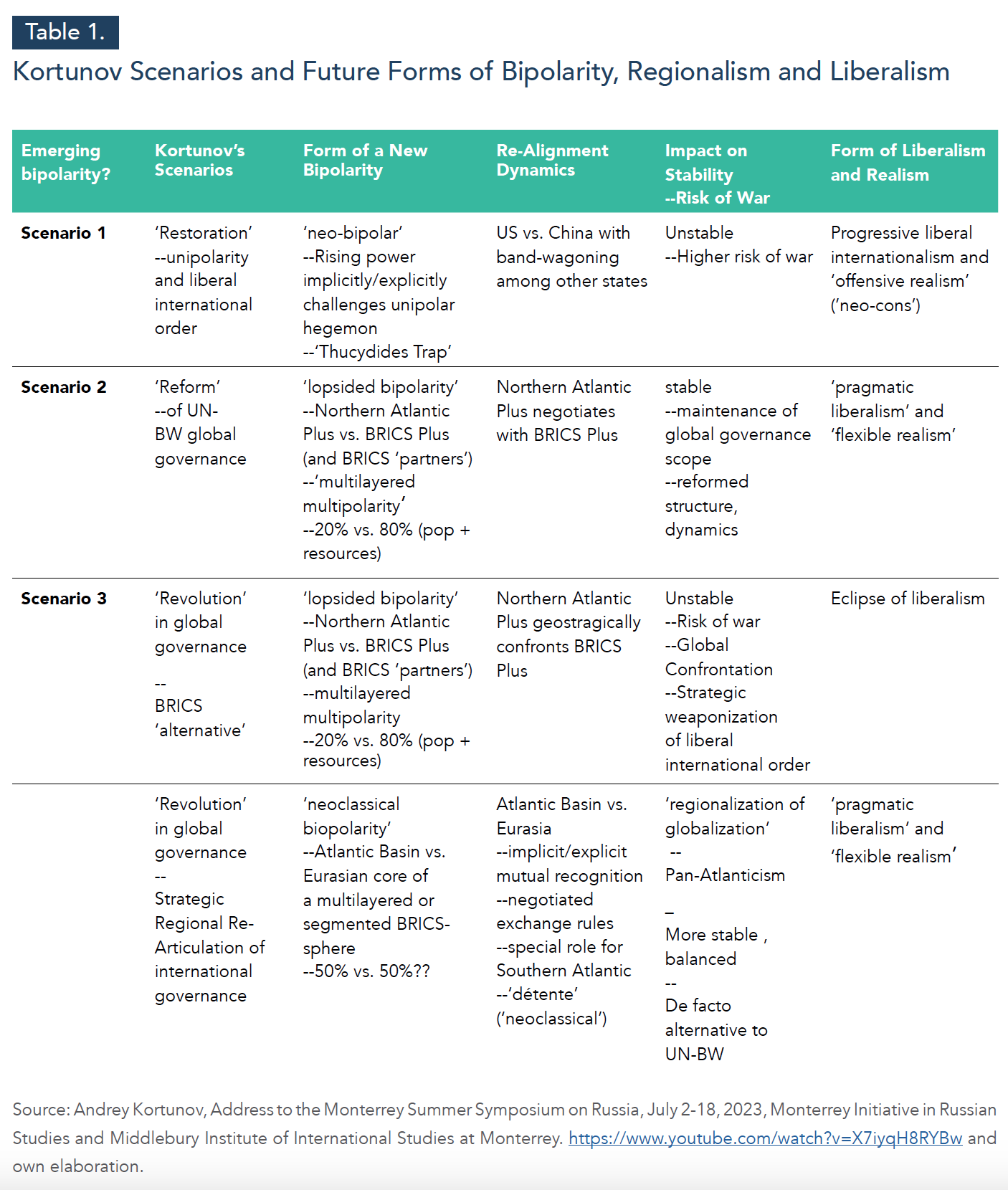

Quo Vadis? Strategic Implications for Regionalism, Liberalism, and the Atlantic Basin

It is true that there is currently little appetite—or policy attention bandwidth—in the Northern Atlantic, particularly in the US, for any new trade agreements in the near future.[42] While several third-generation ‘comprehensive and deep’ trade agreements remain under negotiation, most are bilateral, with discussions often dragging on for years. This includes negotiations for “a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA) between the European Union and Morocco, which were launched March 1, 2013, and are still ongoing”.[43] In the new context of heightened strategic competition between the Northern Atlantic Plus, China, Russia and the BRICS Plus, the US-EU Trade and Technology Council (TTC) was established in the Northern Atlantic in 2021[44] as a ‘second-best’ mechanism following the failure of the TTIP talks and the ongoing absence of a transatlantic trade agreement. However, the TTC’s impact has been marginal so far, driven as much by geostrategic concerns[45] as by liberal universal goals and values. There is considerable skepticism about its ultimate potential.[46] For now, the TTC appears to be another Northern Atlantic Plus mechanism aimed at helping the US reestablish full-spectrum dominance and complete unipolar hegemony at both geoeconomic and geopolitical levels—a strategic bid to pursue Kortunov’s first potential global scenario: restoration (see Policy Briefs 2 and 5 in this series, and Table 1 below).

Protectionism in trade and investment, sanctions, strategic technological decoupling, and international and regional infrastructure projects designed to rival China’s BRI or other BRICS Plus initiatives have been key geoeconomic policies adopted by Northern Atlantic Plus states in their attempt to restore unipolar hegemony and rejuvenate the liberal international order. Conversely, the revival of NATO, its attempts to expand into Ukraine and Georgia, its support for Ukraine against Russia in the ongoing conflict, its recent geostrategic focus on the Indo-Pacific, and its expansion into Asia, along with new strategic coalitions such as the Quad and AUKUS, are central features of a parallel geopolitical strategy aimed at containing China and Russia and further constraining the emergence of multipolarity. However, these persistent geostrategic pressures to restore unipolar hegemony, having pushed Russia and China closer together, now risk tipping the emerging multipolarity into a new type of bipolarity—a ‘lopsided bipolarity’—by unifying large parts of the Rest behind the BRICS Plus and the expanding BRICS-sphere of formal and informal partners.

The debate over whether the strategy of restoring complete unipolar hegemony will succeed or not is likely to continue until its outcome is clear. If the restoration does not succeed, and if a hard conflict over the reform or transformation of global governance can be avoided—avoiding the Thucydides Trap of what we have termed a ‘neo-bipolarity’—geoeconomic logic could pave the way for a new ‘fourth generation’ of regionalism. This would align with the alternative sub-outcome of Kortunov’s third scenario, known as the ‘regionalization of globalization’ (see Table 1 below).

In other words, the evolving structure of the international power system—shifting towards multipolarity and potentially a new form of bipolarity—is pushing the global system either towards conflict, with all its unpredictable consequences, or towards a new trend of regionalization. These dynamics create an opportunity for the concept of pan-Atlantic cooperation and could generate strategic gravity for an Atlantic Basin regional framework for international relations.

Source: Andrey Kortunov, Address to the Monterrey Summer Symposium on Russia, July 2-18, 2023, Monterrey Initiative in Russian Studies and Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterrey. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X7iyqH8RYBw and own elaboration.

Without the development of some form of pan-Atlantic cooperation encompassing both Northern and Southern Atlantic states, or progress towards Atlantic Basin regionalism, the current reconfiguration of international power and the emergence of multipolarity are likely to lead to a drift towards a ‘lopsided bipolarity’—where the Northern Atlantic Plus faces off against the ‘Rest’ of Eurasia-Pacific and the Southern Atlantic (see Table 1). This scenario could exacerbate the potential for conflict, reminiscent of the Thucydides Trap, rather than fostering a peaceful reform of the global system. The BRICS-sphere, with its growing diplomatic pressure, could potentially drive such reform. However, without strategic cohesion in the Atlantic Basin, the risk of potential conflict remains high.

Short of a successful, globally-agreed reform of global governance, only pan-Atlantic cooperation and Atlantic Basin regionalism can stabilize an increasingly unstable global system. Such measures would help avoid the drift towards ‘lopsided bipolarity’—which carries a heightened risk of triggering the Thucydides Trap and potential conflict—and harness the dynamics of globalization within a context where global governance is at an impasse. By fostering a new ocean-basin regionalism, pan-Atlanticism could offer a framework for a balanced Atlantic Basin-Eurasia bipolar power structure, potentially leading to a more stable and interdependent ‘détente’. This form of bipolarity, which we term ‘neoclassical’, would be more balanced than the ‘lopsided bipolarity’ and more stable than the emerging ‘neo-bipolarity’ shaped by US-China rivalry.[47] As argued in Policy Brief No. 4, the Southern Atlantic states will play a crucial role in the development of multilayered multipolarity and influence any eventual international power structure.[48]

In a context many in the Northern Atlantic are referring to as the New Cold War—regardless of the evolving polarity—both realists and liberals might start to envision a new Atlantic Basin regionalism. Although trade agreements may be currently out of favor in the Northern Atlantic, liberal economic cooperation could be rethought, reimagined, and made more appealing across the entire Atlantic Basin. This would be particularly relevant given the ongoing shift from unipolarity to multipolarity and the escalating geostrategic competition with China, Russia and the BRICS Plus.

Reimagining Pan-Atlantic Cooperation from the Liberal Perspective: A Glance Ahead

To advance pan-Atlantic cooperation, it will be necessary to envision a new type of second-best strategy: an ocean basin region, specifically the Atlantic Basin region. Properly conceived, pan-Atlantic cooperation could transform the Atlantic world into an integrated ocean-basin economic and sustainable development space. This cooperation should be based not only on the liberal principles of the GATT, which should serve as benchmarks rather than strict touchstones, but also on a pragmatic design that recognizes both:

- the current realist necessity of corporate and strategic nearshoring (especially for the Northern Atlantic but also possibly benefitting the Southern Atlantic);

- the urgent need for action on climate change and decarbonization, emphasizing increased international climate finance, sustainable development and Atlantic ocean-focused cooperation (involving both the Southern and Northern Atlantic). [ukm1] [PI2]

These complementary imperatives present a significant opportunity to overcome the lingering North-South divide in the Atlantic through a regional initiative for pan-Atlantic cooperation.

A strategic conception of pan-Atlantic economic cooperation—explored further in the next policy brief—could empower Southern Atlantic societies by fostering increased intra-Atlantic investment and trade (driven by strategically-negotiated Western nearshoring and friendshoring in Africa and Latin America), bolstering climate change mitigation and adaptation capacities, and enhancing national autonomy and strategic hedging capabilities.

[1] Liberalism clashes with realism in this regard in the case of both traditional and ‘defensive’ realism but not in the case of ‘offensive’ realism.

[2] See, for example, Bhagwati, Jagdish N., "US Trade Policy: The Infatuation with FTAs", Columbia University, Discussion Paper Series No. 726, April 1995 (https://academiccommons.columbia.edu/doi/10.7916/D8CN7BFM).

[3] The tension is complicated further by the environmentalist imperative to cooperate—at both the global and regional levels—on the challenges in the global commons and their concrete manifestations in the ocean basins.

[4] See C. O’Neal Taylor, “Regionalism: The Seond Best Option?” Saint Louis University Public Law Review, vol. 28., no. 1, 2008.

[5] The US Cold War policy of containment was the result of Kennan’s adaptation of Halford Mackinder’s Heartland theory which he integrates into Nicholas Spykman’s focus on controlling or influencing the rimlands of Eurasia. Given that the Soviet Union, at that time the second most powerful state in the world and on the verge of becoming a fully-fledged nuclear superpower, already completely and securely occupied the Great Eurasian Heartland (control over which was the key to ruling the world for Mackinder), Kennan also considered Spykman’s insistence on the rising strategic priority of the rimlands, given the new post-war prominence of US sea power and the heavily landlocked status of the Soviet Union at the time.

[6] Note on the categories and terminology for different types of economic regionalism and regional cooperation as used in this series of briefs: Generally speaking, we use the term ‘regional trade agreement’ (RTA) to broadly refer to all forms of preferential trade agreements, including bilateral agreements. However, in specific contexts, we refer to them more precisely as free trade associations (FTAs) or PTAs, particularly when they do not encompass an entire region or are not strictly regional in nature.

[7] However, some regionalisms emerged as geopolitical defence mechanisms within Latin America, the Caribbean and Africa. A notable example is ZOPACAS (the South Atlantic Zone of Peace and Cooperation), which, although initially focused on peace, has significantly broadened its scope of cooperation in subsequent ‘generations’ of regionalism, also adopting many of the ocean-based focuses of the PAC’s pan-Atlantic cooperation.

[8] See Glania and Matthes, op. cit., pp. 1-4.

[9] Uri Dadush and Enzo Dominguez Prost, “Preferential Trade Agreements, Geopolitics, and the Fragmentation of World Trade”, published online by Cambridge University Press: 14 April 2023 (https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/world-trade-review/article/preferential-trade-agreements-geopolitics-and-the-fragmentation-of-world-trade/788BA2CB330A716DC130B75CDB2016E8)

[10] Figures from the WTO Secretariat, presented in Vera Thorstensen and Lucas Ferraz, “The Impact of TTIP on Brazil”, Chapter 10 inThe Geopolitics of TTIP: Repositioning the Transatlantic Relationship for a Changing World, Daniel S. Hamilton, ed., Center for Transatlantic Relations, Johns Hopkins University-SAIS, 2014, p. 139.https://archive.transatlanticrelations.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Complete_book.pdf

[11] Uri Dadush and Enzo Dominguez Prost, op. cit.

[12] WTO Secretariat, Number of preferential trade agreements in force by country group, 1950-2010 – Figure B1 in WTO Trade Report (2011).

[13] The Southern African Development Community (SADC) and the EU emerged as new organisations, representing important changes from their predecessors − the Southern African Development Coordination Conference (SADCC) and the European Communities (EC)”. Andréas Litsegård and Frank Mattheis, ‘The Atlantic Space – A Region in the Making’, Chapter 1 in Frank Mattheis and Adreas Litseard, eds., Interregionalism across the Atlantic Space, Springer International Publishing, 2018, p. 6 (https://archive.transatlanticrelations.org/wp-content/ uploads/2016/08/Interregionalism-across-the-Atlantic-Space.pdf)

[14] Ibid.

[15] Glania and Matthes, op. cit., pp 38-42.

[16] Andréas Litsegård and Frank Mattheis, op. cit. p. 6.

[17] During the apogee of the unipolar moment, the influence of Francis Fukuyama’s essay and book on The End of History eclipsed that of Sun Tzu, Clausewitz and Morgenthau in both the Northern Atlantic Plus and the Rest, at least for a time.

[18] See the discussion on regionalism and the WTO in Guido Glania and Jurgen Matthes, “Multilateralism or Regionalism? Trade Policy Options for the European Union,” Brussels: Center for European Policy Studies, 2005, pp. 38-51.

[19] Uri Dadush and Enzo Dominguez Prost, op. cit.

[20] Gabriel Felbermayr, Feodora Teti, and Erdal Yalcin, “Rules of origin and the profitability of trade deflection”, Journal of International Economics, Volume 121, November 2019, 103248 (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0022199619300662)

[21] Ibid.

[22] “FTAs or GSP arrangements should not require proof of origin by default, except for those few products where differences in external tariffs are larger than some threshold level (determined by the additional transportation costs that would arise if firms attempt to exploit tariff differences)”. Gabriel Felbermayr, Feodora Teti, and Erdal Yalcin, “Rules of origin and the profitability of trade deflection”, op. cit.

[23] Bhagwati, Jagdish N., op. cit.

[24] Woori Lee, Alen Mulabdic, and Michele Ruta, “Third-Country Effects of Regional Trade Agreements: A Firm-Level Analysis”, Policy Research Working Paper 9064, World Bank Group, Macroeconomics, Trade and Investment Global Practice, November 2019. (https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/110561574281995016/pdf/Third-Country-Effects-of-Regional-Trade-Agreements-A-Firm-Level-Analysis.pdf)

[25] Aaditya Mattoo, Alen Mulabdic, and Michele Ruta, “Trade Creation and Trade Diversion in Deep Agreements”, Policy Research Working Paper 8206, World Bank Group, Development Research Group Trade and International Integration Team & Trade and Competitiveness Global Practice Group, September 2017. (https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/208101506520778449/pdf/WPS8206.pdf).

[26] Although different contexts have different initial catalysts, this is essentially the same dynamic that results from economic sanctions, a turn to economic autarky, global economic fragmentation or a decoupling of the global economy—a loss of efficiency and global welfare.

[27] In part, this is because creating and maintaining a customs union, let alone a true single market, is a complex and challenging process. However, the US has historically refrained from encouraging the formation of CUs or SMs. This is partly because such frameworks often pave the way toward deeper economic integration, including eventual monetary union and the adoption of a single currency. Such monetary integration could complicate or even directly threaten US dollar monetary hegemony. By contrast ‘deep preferential and free trade agreements’ do not carry the same risk of monetary integration and thus serve as geoeconomic tools that reinforce US hegemony without posing challenges to it.

[28] Aaditya Mattoo, Alen Mulabdic, and Michele Ruta, “Trade Creation and Trade Diversion in Deep Agreements”, op, cit.

[29] This is the argument of the EU, which has essentially become a fusion of a CU/single market with a deep and broad RTA.

[30] See Policy Briefs No. 2 and 3 in this series: Paul Isbell, “The Strategic Significance of Pan-Atlanticism for the West”, Policy Center for the New South, December 19, 2023, PB-45/23 (https://www.policycenter.ma/publications/strategic-significance-pan-atlanticism-west?page=1) and “The Strategic Significance of Pan-Atlanticism for the Rest”, Policy Center for the New South, December 28, 2023, PB-48/23 (https://www.policycenter.ma/publications/atlantic-basin-realism-and-geostrategy-ii-strategic-significance-pan-atlanticism-rest)

[31] See PíaRiggirozzi and Diana Tussie, “Post-Hegemonic Regionalism”, International Studies, International Studies Association and Oxford University Press, Published online: 29 November 2021 (https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190846626.013.657) (https://oxfordre.com/internationalstudies/internationalstudies/abstract/10.1093/acrefore/9780190846626.001.0001/acrefore-9780190846626-e-657)

[32] See Paul Isbell, “The Strategic Significance of Pan-Atlanticism for the Southern Atlantic”, Policy Center for the New South, January 3, 2024, PB-01/24 (https://www.policycenter.ma/publications/strategic-significance-atlantic-basin-and-pan-atlanticism-southern-atlantic)

[33] Along with the USMCA (US-Mexico-Canada Agreement), which served as an update and partial renegotiation of the previous NAFTA.

[34] Daniel S. Hamilton, “TTIP’s Geostrategic Implications,” Summary Chapter in The Geopolitics of TTIP: Repositioning the Transatlantic Relationship for a Changing World, Daniel S. Hamilton, ed., Center for Transatlantic Relations, Johns Hopkins University-SAIS, 2014, p. xv. (https://archive.transatlanticrelations.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Complete_book.pdf)

[35] Ibid.

[36] Vera Thorstensen and Lucas Ferraz, “The Impact of TTIP on Brazil”, Chapter 10 inThe Geopolitics of TTIP: Repositioning the Transatlantic Relationship for a Changing World, Daniel S. Hamilton, ed., op. cit. p. 138.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Daniel S. Hamilton, “TTIP’s Geostrategic Implications,” Summary Chapter in The Geopolitics of TTIP: Repositioning the Transatlantic Relationship for a Changing World, Daniel S. Hamilton, ed., Center for Transatlantic Relations, Johns Hopkins University-SAIS, 2014, p. vii.https://archive.transatlanticrelations.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Complete_book.pdf

[41] However, Trump, like Nixon and Kissinger before him, at least in formal terms, is something of a ‘neo-realist’—not so interested in regional economic cooperation and certainly not averse to turning up unexpected pressure on his allies as well, especially if they are economic competitors or recipients of US assistance. This Kissingerian ‘discipline-the-allies-too’ approach was apparent in Trump’s steel and aluminium tariffs on European countries in 2017-18, and in his threats to withdraw from NATO if the European members did not cover more of the burden for military expenditure and deployment.

[42] See, for example, Adam Behsudi, “‘We’re not going back’: The U.S. and Europe are entering a new trade era”, Politico, June 3, 2023 (https://www .politico.com/news/2023/06/03/us-europe-china-trade-00099954).

[43] As of January 1, 2024, Morocco has PTAs with 62 countries. Chief among these are: (1) the EU-Morocco Association Agreement, which entered into force on March 1, 2000,covering industrial goods and some agricultural products; (2) the US-Morocco Free Trade Agreement (USMFTA), the only US FTA in Africa, which entered into force in 2006, is ‘comprehensive’ and includes chapters detailing commitments on intellectual property rights, labor, and environmental protection; (3) the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), which came into effect on January 1, 2021, but which Morocco has not yet formally ratified, despite the fact that on February 22, 2019, the Moroccan government council adopted a bill to ratify the agreement. Morocco also has ongoing negotiations for FTAs with Canada and many West African countries, having applied to join the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) in 2017). Later that same year, Morocco began talks with Mercosur. In November 2017, Morocco began negotiations with the South American trading bloc Mercosur to establish a free trade area. See: International Trade Administration (US ITA), “Trade Agreements”, Morocco – Country Commercial Guide, (https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/morocco-trade-agreements). The logic for this cooperative economic outreach is reinforced by the interregional trade agreements between Mercosur and Southern Africa (the South African Customs Union, SACU, and the SADC; see Policy Brief No. 4 in this series). Regardless, Morocco has yet to secure entry into any other trade bloc in the Atlantic Basin.

[44] See the European Commission: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/stronger-europe-world/eu-us-trade-and-technology-council_en

[45] See the White House Briefing Room release: https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2024/04/05/u-s-eu-joint-statement-of-the-trade-and-technology-council-3/

[46] Adam Behsudi, op. cit.

[47] For more on my concepts of ‘neo-bipolarity’, ‘lopsided bipolarity’ and ‘neoclassical bipolarity’, see Policy Paper No. 2 in this series: Paul Isbell, “The Strategic Significance of Pan-Atlanticism for the West”, Policy Center for the New South, December 19, 2023, PB-45/23 (https://www.policycenter.ma/publications/strategic-significance-pan-atlanticism-west?page=1)

[48] Paul Isbell, “The Strategic Significance of Pan-Atlanticism for the Southern Atlantic”, Policy Center for the New South, January 3, 2024, PB-01/24 (https://www.policycenter.ma/publications/strategic-significance-atlantic-basin-and-pan-atlanticism-southern-atlantic).

[ukm1]I have had a formatting issue here and been unable to insert the second bullet point.

[PI2]Me too