Publications /

Opinion

“This opinion was prepared within the framework of the Jean Monnet Atlantic Network 2.0. The European Commission's support for the production of this publication does not constitute an endorsement of the contents, which reflect the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.”

As part of the lengthy fight against climate change, the European Union (EU) has introduced a Border Carbon Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), among its "Fit for 55" package, intended to deliver the EU's intermediate target of reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 55% from 1990 levels by 2030. This proposal is deemed "bold, complicated, even controversial." If implemented, it will undoubtedly disrupt trade relations between the EU and its main partners and transform energy dynamics in the Atlantic basin. The CBAM aims to introduce a carbon price to imported products inside the EU equivalent to the carbon price applied to products manufactured by EU producers under the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS). It "would require importers to purchase carbon emissions certificates for imports that the EU determines are not produced under emissions standards similar to those of the EU." While the sentiment behind the CBAM is commendable - several countries have indeed welcomed the proposal - others have expressed concerns about its application, noting several issues that may arise from it.

The Case for the CBAM

Given that climate action is a transboundary challenge, national or local action cannot solve it alone. Through the CBAM, the EU hopes to level the fields on the fight against climate change by incentivizing developing countries to reduce their GHG emissions and providing fair competitive conditions for local firms that develop low-carbon products. As the EU raises its climate ambitions, it is increasingly wary of the risk of carbon leakage, which characterizes a situation where production moves outside the EU to areas with less stringent climate regulations, potentially undermining the EU's climate efforts. Although there is little or no evidence of carbon leakage to date, the EU aims, through the CBAM, to reduce the risk of carbon leakage, thus equalizing the price of carbon between domestic products and imports.

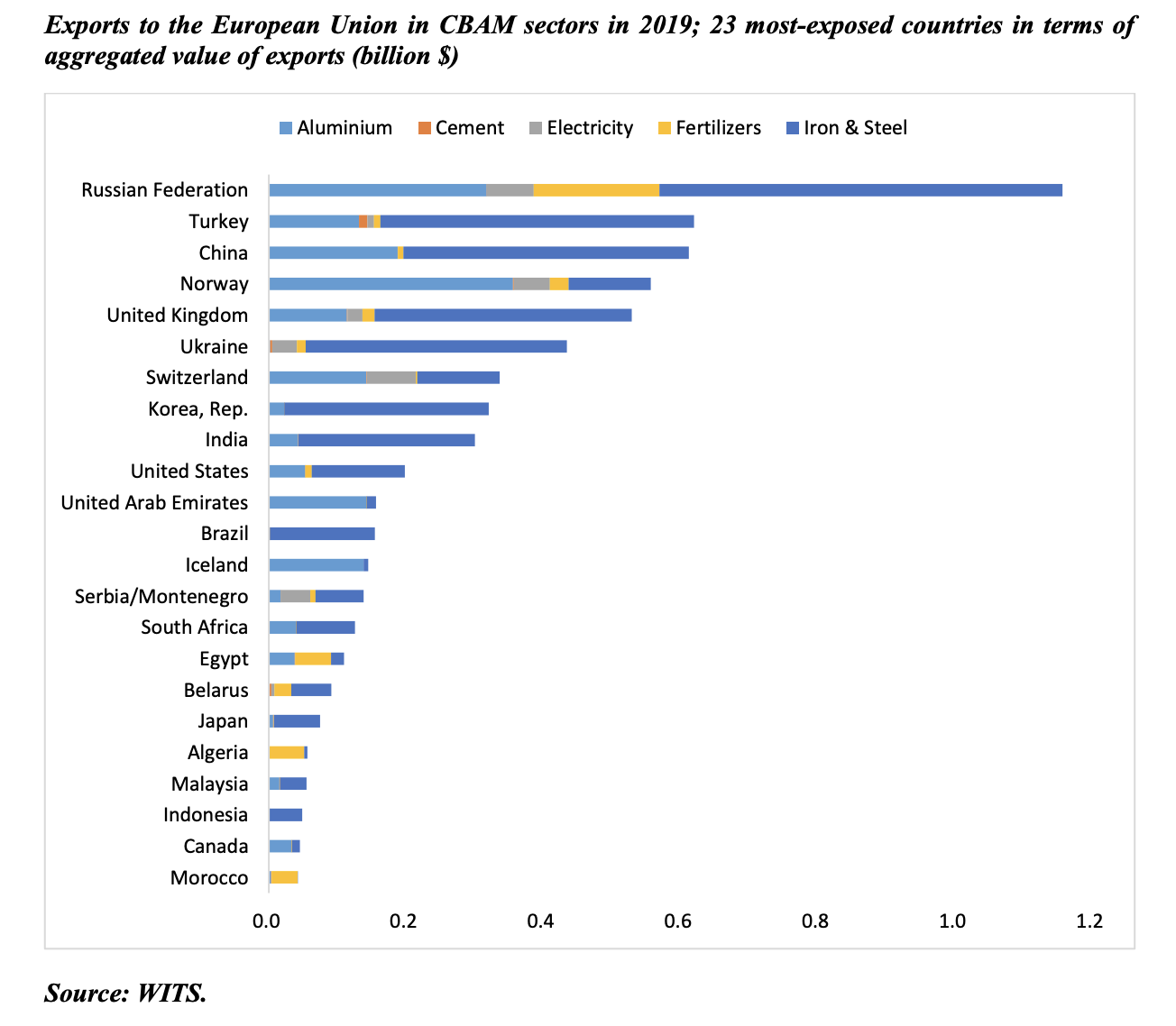

An initial transition period of three years, beginning in 2023, is foreseen to allow companies and trading partners some time to adjust. During this transitional period, the CBAM will initially apply only to selected products from heavy industries deemed as high risk of carbon leakage and highly GHG emissions-intensive. These products are iron and steel, aluminum, cement, fertilizers, and electricity production. By the end of the transition period, importers to the EU will start paying a financial adjustment, and the scope of the CBAM may be extended to a broader list of products and services, including down the value chain. It may also consider indirect emissions, such as those from the electricity used to produce the goods.

According to the official CBAM proposition, this mechanism will apply to all non-EU partners without exemptions for the Least Developed Countries (LDCs). The only exception is for partners who participate in the ETS or have an emission trading system linked to the EU's like the European Economic Area and Switzerland.

The Issues Raised by the CBAM

The CBAM proposal has faced severe scrutiny from many EU partners, who are skeptical about its effectiveness in achieving its stated objectives, its effect on the World Trade Organization (WTO), and its consistency with the Paris agreement.

The first concern relates to the substantial costs that non-EU partners are likely to face due to increased tariffs on CBAM goods imported into the EU. Countries like Russia, Turkey, or China may be among the most impacted in terms of the value of EU imports. But low- and middle-income countries in Africa could also be affected, especially if they are dependent on exports to the EU and if the carbon intensity of their production is relatively high. Examples of countries might include Mozambique for its aluminum exports, Zimbabwe for iron and steel, Morocco, and North African countries for fertilizers. With the price of the EU ETS recently exceeding €50 per metric ton of CO2 equivalent emissions, the additional costs potentially generated by the CBAM are not insignificant.

The second concern pertains to the negative implications of the CBAM for the already fragile global trading system. Admittedly, the CBAM can technically be presented as WTO-compliant as it does not discriminate between EU firms and their trading partners. However, if other countries opt for such systems, the structure of each national scheme will vary, as will the many assumptions needed to calculate the appropriate tax in each case. Thus, carbon border taxes will differ not only by country of destination and product but also by country of origin and company, a practice that would significantly depart from the WTO's most favored nation principle. In addition, the CBAM requires producers to verify the GHG emissions embodied in their products. This can impose a significant technical and administrative burden on LDCs, which already face some of the highest trade barriers in the world, as they may not have the capacity to calculate these emissions and manage this mechanism.

The third concern revolves around the non-compliance of the CBAM with the Paris Agreement. The CBAM can be envisaged as departing from the Common but Differentiated Capacities and Responsibilities Principle under the Paris Agreement. Since there is no exception for the LDCs, this mechanism would penalize countries that are the least responsible for the climate crisis but the most affected by it. Other issues raised by the CBAM pertain to the use of its revenues. The European Commission advocates for the retention of all revenue for the EU budget, thus contributing fractionally to the repayment of the EU's €750 billion new generation debt. Yet, recycling carbon pricing revenues to address equity concerns outside the EU could be a way for the EU to support the energy transition in LDCs.

How did countries react?

Some countries like Canada have signaled their interest in the CBAM. Like the EU, Canada "recognizes the role of carbon pricing as a powerful and efficient way to fight climate change, and has put forward strengthened approaches to pricing carbon while addressing the risk of carbon leakage." Both Canada and the EU have committed to work together on carbon pricing and WTO-compatible border carbon adjustments in the context of the Canada-European Union Summit in June 2021.

In the United States, President Biden has voiced his support for a CBAM for the United States, which could potentially help the US align with the EU and accelerate climate action. But President Biden has not made the issue a priority, given that the CBAM does not yet have majority support in Congress. In the run-up to COP 26, the US and EU reached a deal on their longstanding dispute on aluminum. The two countries agreed on greener production standards for steel and aluminum. They issued a joint statement committing to work together to establish mechanisms that discourage imports whose production and consumption emit high levels of greenhouse gas (GHG). Yet, there were no discussions of this in Glasgow.

On the other hand, the CBAM is viewed as illegitimate by many developing countries. Brazil, China, India, and South Africa formally communicated their strong opposition to the CBAM at the end of their April 2021 BASIC group meeting on climate change. These countries argued that any measures to address climate change must be consistent with multilateral trade rules and must not impose arbitrary restrictions on international trade. Russia has also been outspoken in its criticism towards the CBAM; its economic development minister has suggested the measure will be challenged at the WTO.

While the CBAM is a well-intentioned effort to encourage decarbonization outside its borders and create the necessary political space to adopt stricter carbon targets within them, it introduces enormous complexities. It could exacerbate global trade tensions and undermine the already fragile foundations of the world trading system, and can be perceived as non-compliant with the Paris Agreement by developing countries. At the same time, the CBAM proposal is a wake-up call for all countries that the time is ripe for a more concerted and comprehensive decarbonization effort. Even if the CBAM is not implemented in its proposed form, it is likely the precursor of tighter carbon regulations, standards, and taxes that could take various forms in the future.

The issue of CBAM raises another equally important issue, especially for developing countries, namely that of equity in the transition to a low-carbon economy. The latter undoubtedly presents new challenges related to the reskilling of people working in industries deemed "carbon-intensive" and stranded fossil fuel assets, to name a few. These challenges must be addressed first to gain acceptance from countries and their populations.