Publications /

Policy Brief

This brief argues for a pan-African food security initiative that would: 1). encourage free trade in food products between African countries; 2). promote multi-country regional investments in infrastructure to enhance agricultural productivity and resilience to climate change; 3). support public-private partnerships to establish fertilizer factories across the continent; 4). create an African council responsible for coordinating and encouraging agricultural research and development; and 5). support a facility that would ensure vulnerable African countries can finance food imports in times of crisis.

INTRODUCTION

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has led to a spike in food prices and has heightened concerns about food security. Leaders from a number of countries and organizations met in September 2022 in the margins of the United Nations General Assembly meetings and issued a declaration on global food security. Food security was also a key point of discussion at the World Bank and International Monetary Fund Annual Meetings in October 2022.

Africa has been at the center of the food security discussions. It is, after all, the continent with the highest incidence of undernourishment. Moreover, widespread hunger, and even famine, threatens large numbers of people on the continent, especially in the Horn of Africa. The main recommendations coming out of the international discussions have been that African countries need to strengthen social safety nets, increase investments in research and development, and avoid trade restrictions, while their partners need to provide more resources to humanitarian organizations such as the World Food Program (WFP), and more generally to agricultural development in Africa.

In this brief, I argue for a pan-African food security initiative that would complement country-specific efforts. It is unrealistic to expect each of the 54 African countries to achieve food security individually. However, working together, Africa, with its population of 1.4 billion people and its vast natural resources, should be able to ensure food security for all.

A pan-African food security initiative could be based on five pillars. First, the secretariat of the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) could be given a specific mandate to ensure the free flow of food products between African countries. Second, the African Union (AU) Commission for Agriculture could work with the African Development Bank (AfDB), the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), and the World Bank to identify regional infrastructure projects, especially in irrigation, to support agriculture and help develop African ‘bread baskets’. Third, the private sector arms of the AfDB and the World Bank could work with African fertilizer producers (e.g. OCP in Morocco and Dangote in Nigeria) to establish more fertilizer factories across the continent. Fourth, African leaders could establish an African Council of Agricultural Research with the task of coordinating research and development (R&D) activities across the continent. Fifth, there is a need to build on the work of the AFREXIMBANK, to ensure that sufficient funding is available to finance vulnerable countries’ food imports during crises.

The Food Security Crisis

According to the FAO-WFP Hunger Hotspots Report of October 2022, acute food insecurity is rising globally. The number of people who will need urgent food assistance could reach 222 million over the next few months. This is the largest number ever recorded since the two organizations started producing the ‘Hotspots’ report seven years ago. There are at least four reasons for this increase in food insecurity: economic dislocation and supply chain shocks caused by the pandemic, an increase in extreme weather related to climate change, a continuation (or even intensification) of conflict and insecurity, and the rise in world food prices caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The situation is further complicated by constraints on the availability of financing for humanitarian organizations. In a note on food security in Africa, the IMF estimated that food aid per capita for the region has declined considerably over the last decade—to 30% lower than the previous decade. The situation became more challenging over the past two years. Heavy reliance on deficit spending during the pandemic, rising interest rates, and higher debt are limiting the resources available for humanitarian interventions and development assistance. To make things worse, the war in Ukraine is absorbing donor resources that could have been channeled to the developing world. Moreover, even when resources are available delivering aid to the needy is often hampered by conflict and violence.

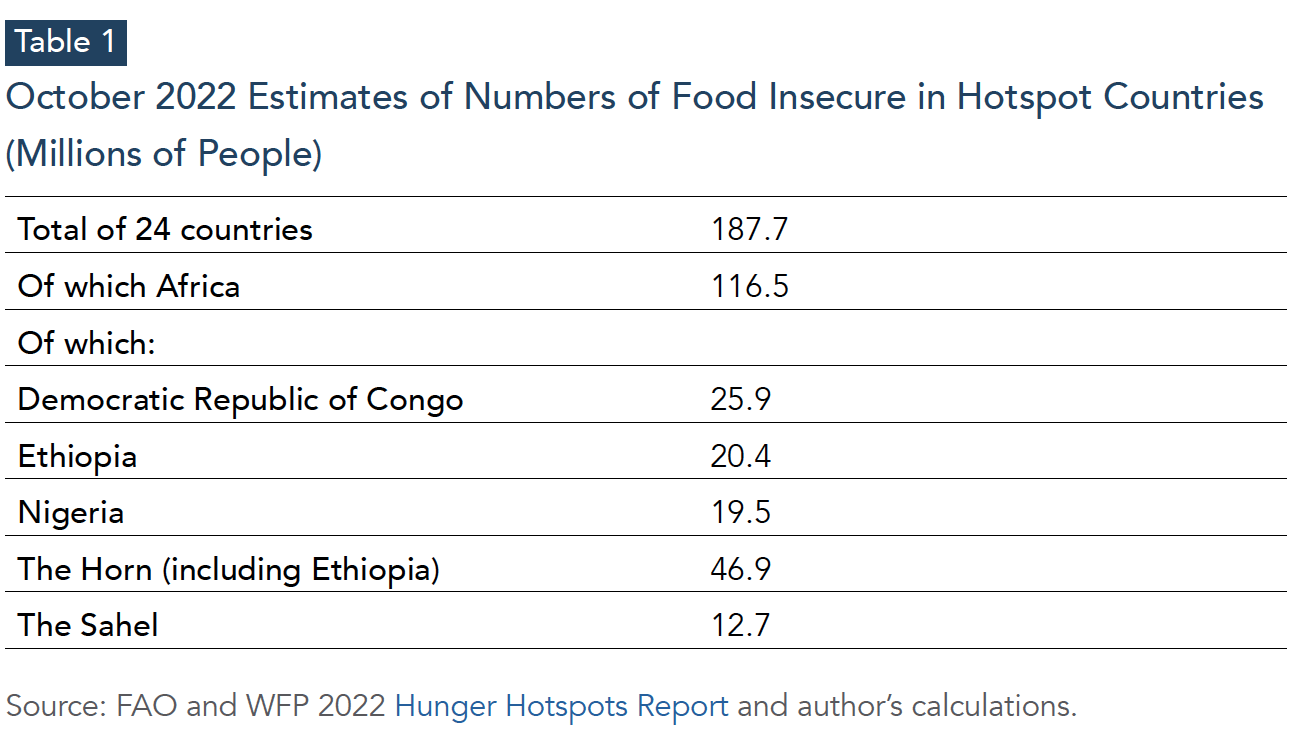

Of the 24 countries classified as hunger hotspots by FAO and WFP in 2022, 16 are in Africa. And Africans make up 62% of the total number of food insecure in hotspot countries (Table 1). Three countries—DRC, Ethiopia, and Nigeria—account for more than 56% of the food insecure in Africa. The three countries share two characteristics: conflict and insecurity in some of their regions, and high vulnerability to climate change.

The number of food insecure has been declining slowly in the DRC. The number of people facing food insecurity there is estimated at 25.9 million, which is slightly lower than the 27.3 million estimated for the same period last year. That occurred in spite of the pandemic and the spike in food prices caused by the war in Ukraine. However, the situation remains concerning. Conflict and instability continue to be serious concerns in the eastern part of the country (especially North and South Kivu and Itouri), and rainfall has been below average for the entire country.

Food insecurity in Northern Ethiopia has increased because of the conflict, particularly in Tigray but also affecting Afar and Amhara. The resumption of hostilities in August 2022 after five months of truce does not augur well for the food-security situation. This is made worse by the most severe drought in recent history, affecting the southern and eastern areas of the country. Ethiopia is also a net food and fuel importer; high international prices have had a negative impact on its balance of payments and have led to a currency depreciation on the parallel market. Food price inflation averaged 40% during the first half of 2022.

Nigeria’s food insecurity has usually been concentrated in the North, especially in Borno, Adamawa, and Yobe states. In 2022, while Northern Nigeria was suffering from drought, Southern Nigeria (like the rest of West Africa) was hit by devastating floods. Conflict and insecurity have been rampant across Northern Nigeria because of attacks by militant groups, increasing incidences of kidnap for ransom, and intercommunal violence. Floods have hit 27 Nigerian states since February 2022, with Anambra, Bayelsa, Cross River, Delta, and Rivers states the most impacted. About 450,000 hectares of farmland have been damaged, and the 2022 harvest has been seriously compromised. Increasing global commodity prices have made matters worse, and food price inflation rose to 30% and is likely to remain high for the remainder of 2022.

The Horn and the Sahel are particularly prone to food insecurity. According to the FAO-WFP report, about 47 million people in the Horn and 13 million people in the Sahel are food insecure. Once more, the regions with high incidence of food insecurity are characterized by conflict and by vulnerability to climate conditions. The Horn has been subject to the worst drought in many years, affecting parts of Kenya, Ethiopia, and Somalia. Flooding has severely impacted agriculture in South Sudan. These climatic shocks coming after the locust infestation of 2019-2020, which affected 1.25 million hectares of land in Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia, have had huge negative consequences for food security in the region. Political instability and conflict in Ethiopia, Sudan, South Sudan, and Somalia have made the situation even worse. The Sahel (Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger) has seen a 50% increase in food insecurity compared to 2021. This is a reflection of the sharp increase in political instability and conflict (Mali, Chad, Burkina Faso), and rising world prices for food, fuel, and fertilizers.

Food Insecurity in Africa is a Long-term Challenge

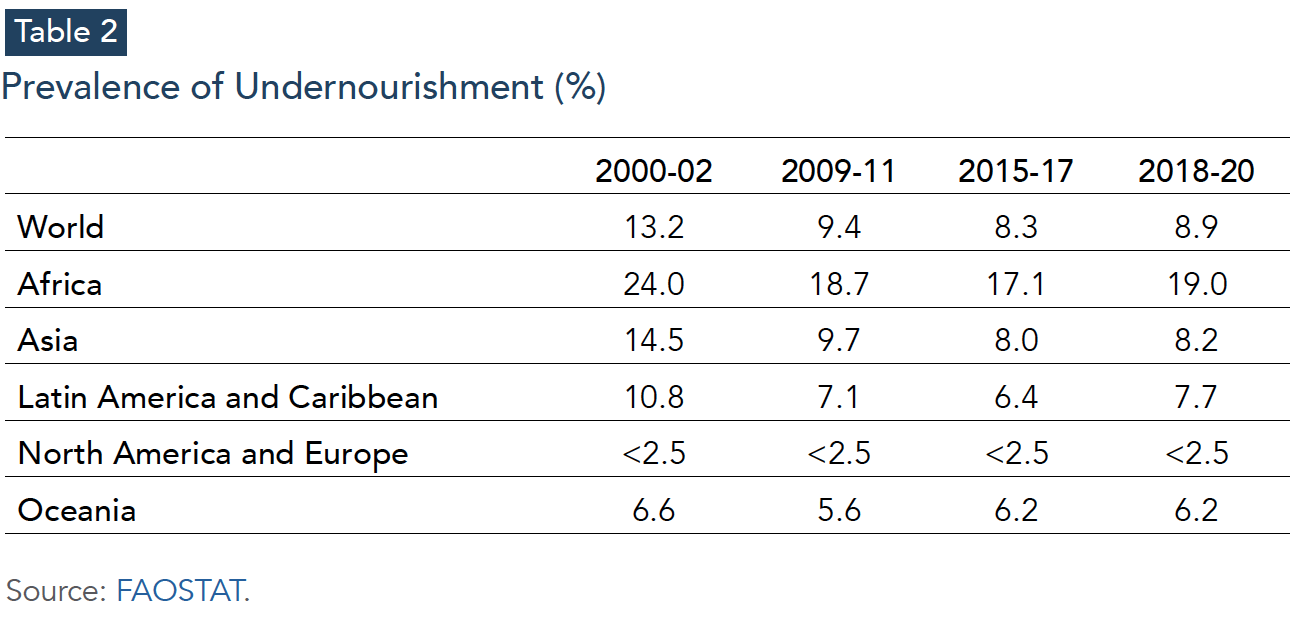

High levels of food insecurity are not new in Africa. The pandemic and the high food prices caused by the war in Ukraine have made things worse, but they are not the root causes of the problem. Food insecurity on the continent will not go away as the pandemic ends and world food prices decline. Table 2 shows that the prevalence of undernourishment in Africa, while it has been declining slowly, has remained about double the world average over the last two decades, and that the problem predates the pandemic and high food prices.

Table 2 shows that about one in every five Africans is undernourished. This is in turn reflected in very high child malnutrition rates. Nearly one-third (31%) of African children under five years old are stunted. This is the highest stunting rate in the world (the second highest is Asia with a rate of 22%). Stunted children do not achieve their full physical and mental growth potential. That is, the futures of those children (and of their continent) are compromised.

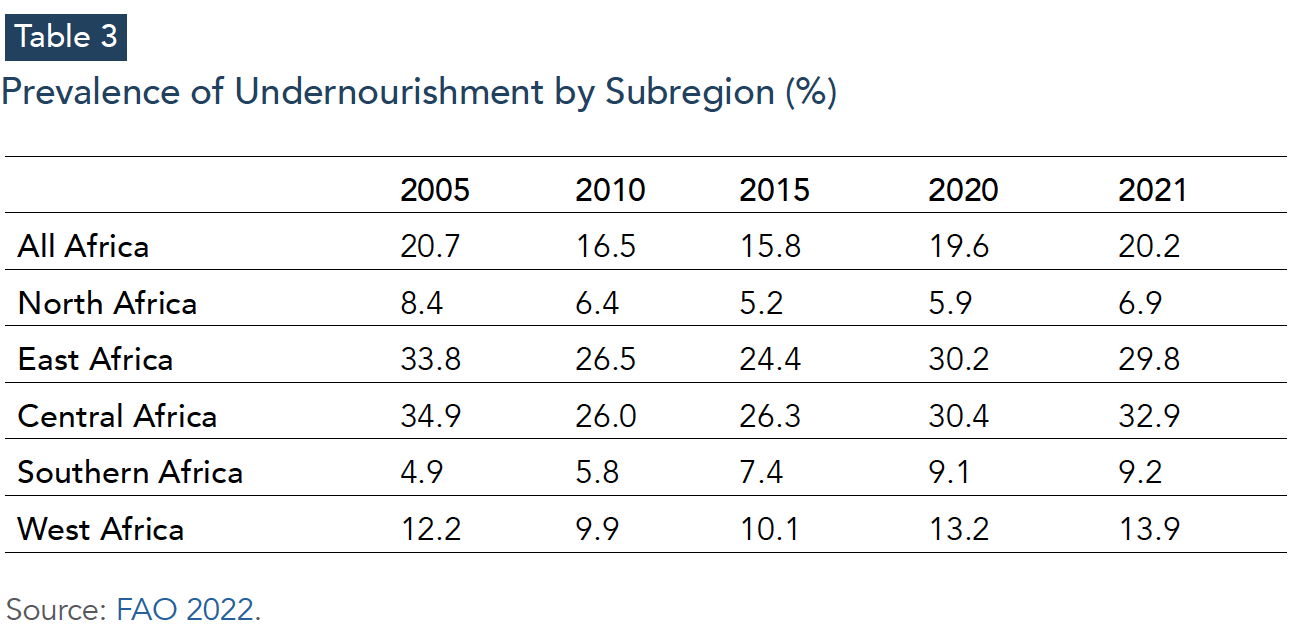

Table 3 reveals two important facts. First, the biggest problem of food insecurity in Africa is in two subregions: East and Central Africa, where the prevalence of undernourishment hovers around 30%. Second, nearly all of the gains in terms of improved food security between 2005 and 2015, when Africa’s prevalence rate fell from 20.7% to 15.8%, were eroded in the five subsequent years as the prevalence rate rose again to more than 20%. This rise in undernourishment started before the pandemic and long before the war in Ukraine. The data indicate that to reduce undernourishment in Africa, it is necessary to tackle the structural drivers of food insecurity, and that special attention needs to be paid to the East and Central Africa subregions.

High incidence of undernourishment is occurring, although Africa spends more than $50 billion/year on food imports. The continent is a large net importer of food, with its cereal import-dependency ratio standing at 31%. Asia has the second highest cereal import- dependency ratio, and it is only 8%. The largest net importers of food on the continent are Egypt ($10.6 billion), Nigeria ($5.3 billion), Angola ($2.3 billion), and Somalia ($1.5 billion).

A clear conclusion from all of this is that Africa is not growing enough food. There is a need to enhance agriculture’s performance to improve food security, and to improve the lives of the millions of smallholder farmers across Africa. The importance of agriculture in Africa cannot be over-stressed. Its share in total employment is around 50% (compared to a world average of 30%), and its share in the continent’s GDP is 20% (compared to a world average of 5%).

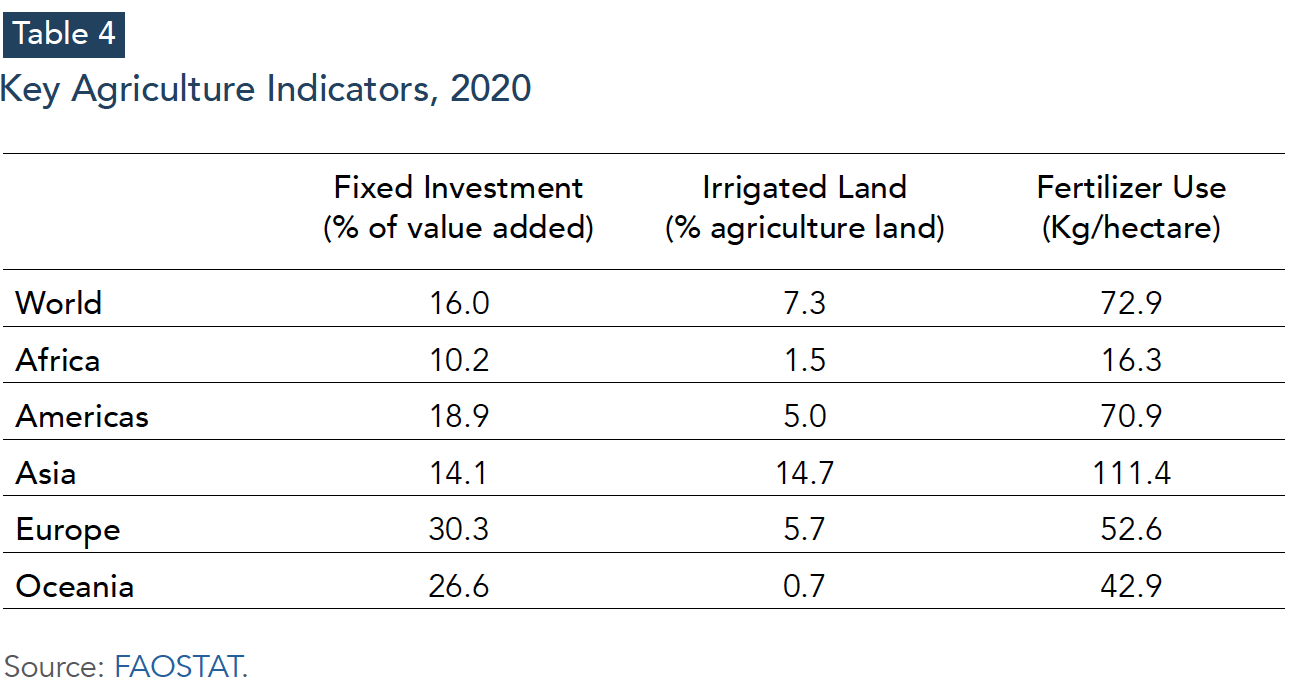

African agriculture is the least productive of all regions of the world. In 2020, the average yield of cereals in Africa was 1.65 tons/hectare, less than half the world average of 4.07 tons/hectare. Moreover, if nothing is done to correct this, those very low African crop yields are projected to decline by an additional 5% to 17% by 2050 because of climate change. The data in Table 4 provide an explanation for this low productivity. Africa lags the rest of the world in agricultural investment, in the share of land under irrigation, and in fertilizer use. Investment in agricultural research and development in Africa averages around $50 per farmer, which is much lower than the rest of the world. For example, Brazil’s spending on research and development averaged $1,200 per farmer in 2000.

Why is Africa under-investing in agriculture, and what in particular can explain African agriculture’s technological stagnation? It is hard to identify a single binding constraint that explains the low productivity of African agriculture. The literature mentions six constraints:

-

First, credit, liquidity, and savings constraints limit the ability of poor smallholder farmers to finance investments, as well as the ability of governments to spend on much needed research and development and rural infrastructure.

-

Second, the lack of developed insurance markets, together with the riskiness inherent in rainfed agriculture in Africa, especially as climate change leads to an increased frequency of severe weather events, is a disincentive for investing, since the return on investment is very uncertain.

-

Third, African farmers have very little access to information about new technologies, or about market opportunities for their products.

-

Fourth, poor quality infrastructure increases transaction costs and limits access to input and output markets. As a result, the cost of inputs in Africa is often higher than in developed countries (60% of fertilizers used in Africa are imported), and farmers get paid less for their products. Moreover, as a result of infrastructure problems, post- harvest losses at the farm level range between 4% and 8%.

-

Fifth, because of the low population density in many of Africa’s rural areas, and labor market imperfections, it is often difficult to find farm workers when they are needed.

-

Sixth, land markets are also imperfect, and property rights especially are not always secure, which discourages long-term planning and investment.

Responding to the Crisis

The issue of global food security, and especially food security in Africa, was high on the agendas of the United Nation’s General Assembly Meetings in September 2022, and the IMF and World Bank Annual Meetings in October 2022. The first decision in all of those meetings was to call for increased financing for food-security operations in developing countries in general, and especially in Africa. The European Commission announced on September 24, 2022, that it is allocating €600 million to finance immediate humanitarian food aid, food production, and resilience of food systems in the most vulnerable countries in Africa, the Caribbean, and the Pacific. Similarly, the World Bank increased its support for social safety nets, and for resilience of agriculture food systems.

Those efforts are obviously laudable and necessary. However, they appear insufficient. The IMF estimates that $5 billion to $7 billion in further spending is needed to assist vulnerable households in 48 countries around the world, and an additional $50 billion is required to end acute food insecurity over the next 12 months. For example, the European Commission allocates €20 million out of its €600 million fund to Somalia. Compare that with Somalia’s net food imports, which amount to about €1.5 billion. Again, it is worth repeating that the efforts by the EU, the World Bank, and others in the international community to support Africa’s food security are commendable. But they need to be further increased. Perhaps more importantly, they need to be supplemented by additional efforts by African countries and African institutions.

In addition to the consensus that the international community should provide more financing for food security, there appears to be general agreement on what African countries themselves must do to achieve food security.

In their papers on food security in Africa, referenced here and discussed at their Annual Meetings, both the IMF and World Bank argue that African governments need to restructure their agricultural spending, and especially to reduce all subsidies, especially those on agricultural inputs. The World Bank’s report notes that in 2006, African governments agreed to spend at least 10% of their budgets on agriculture. Yet more than 15 years have passed and that commitment is still not met—governments spend barely half that amount, on average. In view of the very tight fiscal constraints facing all African governments, it seems pragmatic to suggest, at least in the short term, a reallocation within the agriculture budget, rather than an overall increase in that budget.

Decisions to reduce spending on subsidies (on fertilizers or other inputs) are always controversial. On the other hand, there is no controversy on which spending items need to be increased. Most international organizations and domestic and foreign advisors encourage African governments to significantly increase spending in four areas to enhance food security: social safety nets, infrastructure that supports agriculture, research and development, and digitalization.

African governments, with support from their international partners, rely increasingly on ‘adaptive’ safety nets to help vulnerable families avoid undernourishment. Adaptive safety nets are safety-net programs that can be expanded vertically (provide more assistance to the same recipient), or horizontally (expand the number of recipients), in response to shocks. During the pandemic, most African countries expanded the use of safety-net programs to support people (often in the informal sector) who were impacted by the economic slowdown. Those programs mostly took the form of direct cash transfers, but also sometimes included cash for work or food for work. Those same programs are now being used to help the vulnerable deal with the food crisis. An important feature of many safety-net programs is that they target women, who are usually the most vulnerable to economic slowdowns and food insecurity.

In addition to safety nets, there is consensus that Africa needs to invest more in irrigation and transport infrastructure. The increased frequency of droughts and flooding increases the risks associated with rainfed agriculture. This riskiness could be reduced by more irrigation, which in turn would encourage farmers to invest in better inputs and technologies, thus increasing yields. Investments to increase the share of irrigated land in total agricultural land are considered high priority. Transport infrastructure is also important for agriculture, to help reduce the cost of inputs and to reduce post-harvest losses. Africa needs better roads, rails, and ports to improve food security.

Most observers also argue that African governments also need to spend more on research and development. Since agricultural technology is often region-specific because of differences in the types of soil, temperatures, and water availability, technologies cannot simply be imported and used immediately. At a minimum, they need to be adapted to the regional context—hence the need for African research and development. The problem of lack of new agricultural technologies to be used in Africa can only be solved by increased African investment in research and development.

Finally, Africa needs to invest more in digitalization. This would include digital infrastructure to improve access, the development of public platforms, and digital education. Use of digital technology could help farmers adapt to climate change, increase yields, and better integrate into markets. Remote sensing using drones would support irrigation management, crop spraying, and crop inspection. Satellite imagery and artificial intelligence could be used to fight pests. For example, they were used in 2020 to identify and destroy swarms of locusts in East Africa. Mobile phones could be used to help farmers access mobile banking, early warning systems, market and weather information, peer learning, and agriculture extension services.

Opportunities for Greater African Cooperation

The policy agenda discussed in international fora, and described in the previous section, focusses on country-level efforts to reallocate government spending in order to prioritize safety nets, infrastructure investment to support agriculture and adapt to climate change, research and development, and digitalization. It is an approach that appears to make sense, especially if accompanied by increased support from the international community. However, it is doubtful that on its own this agenda will successfully achieve food security in Africa. Country-level efforts need to be complemented by continent-wide interventions.

Only a small fraction of the 54 African countries can achieve food security on their own. Even Nigeria, Africa’s giant, has problems achieving food security. The challenge facing the smaller countries, especially those that are landlocked, is of course much greater. Country- level interventions need to be supported by Africa-wide initiatives. Working together, African countries can achieve food security for all Africans. This would require: free trade in food among Africans based on the AfCFTA; financing for regional irrigation and transport projects; developing more private-public partnerships for fertilizer production; creating an African Council of Agricultural Research; and supporting and expanding a system for financing food imports in response to shocks that is being developed by the AFREXIMBANK. It is important to stress here that the full benefits from these interventions will only be achieved if there is peace and security across the continent.

The AfCFTA offer a major opportunity for the continent as it connects a growing population of more than 1.4 billion people, and a market of $3.5 trillion. Trade is an important tool for achieving food security. It allows for the flow of food products from surplus to deficit countries. Currently, only about 15% of food imports are intra-African. By allowing for an easier flow of food products, AfCFTA would enhance Africa’s food security. The impact of the war in Ukraine, and the ensuing imposition of 52 food export restrictions by countries around the world, provides an important lesson for Africans: they need to prioritize intra- African trade in food products, and make sure that they do not restrict trade among themselves. Beggar (or in this case starve) thy neighbor policies should not be acceptable in Africa.

The AfCFTA secretariat could be charged with the job of ensuring the free flow of food products. The secretariat, based in Accra, currently has seven directorates, including a directorate for trade in goods. It may be useful to treat food as a special good. That would imply splitting that directorate in two: one directorate responsible for trade in agriculture and food products, and another for other goods. The mission of this directorate would be to ensure the free flow of food products between all African countries; it would be a key contributor to food security on the continent. Its work will need to be complemented by investment in transport and other trade-facilitation infrastructure to ensure that policy decisions on free movement of food are actually implemented.

When Africa becomes a single market for food, investment decisions could be made on purely economic grounds, and should not be influenced by countries’ individual desires to achieve food independence. There are several potential food baskets in Africa (e.g. in Sudan, Tanzania, Nigeria, etc.). Therefore, the African Union commission for ‘agriculture, rural development, blue economy, and sustainable environment’ could be tasked with identifying regional investments, especially in irrigation and other infrastructure, that would develop some of those food baskets with benefits for the whole region. FAO, AfDB, and the World Bank would be important partners to identify and finance those projects.

Fertilizer prices in some African countries are more than double those in the United States, which discourages farmers from using them, and explains the very low rate of fertilizer use on the continent. About 60% of the fertilizers used in Africa are imported. This, together with the large distances and poor transport infrastructure, explains the high fertilizer prices. An obvious option for governments is to subsidize fertilizer prices, which is what many countries have been doing. However, this policy has not succeeded in raising fertilizer use, and is fiscally unsustainable.

A more promising approach would be to increase fertilizer production in Africa, bringing fertilizer plants closer to the farmers to reduce costs. Africa already has two large fertilizer producers. OCP in Morocco is one of the world’s largest phosphate, fertilizer, chemicals, and mineral industrial companies in the world. The Dangote group in Nigeria opened in March 2022 one of the largest ammonia and urea fertilizer plants in the world on the outskirts of Lagos. These two producers, and others, could be encouraged to build new plants across the continent. The private sector arm of the AfDB, and the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation, could be important partners in this work.

It is necessary to increase long-term investments in research and development (R&D) in Africa. R&D expenditures per farmer in Africa today are two orders of magnitude lower than in developed countries. That is, the required increase in R&D expenditures is huge. It may not make sense for each of the 54 African countries to try and build its own world-class R&D center. It is true that differences in soils, water, and climatic conditions require context- specific R&D. However, there are also economies of scale in research.

Africa can learn from India’s experience in agricultural R&D. After all, India’s population is larger than Africa’s, and there is a great deal of heterogeneity among the 28 Indian states. India has sustained an R&D effort since the green revolution. This led to several generations of new varieties, continually increasing yields, and improving nutritional status. Since 1970, India has been producing 20-40 new varieties of rice every year. This work is led by the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR), which was established in 1929 as an autonomous body responsible for coordinating agricultural education and research all over India. ICAR has 14 national research centers.

Africa needs agricultural R&D centers of excellence. A possible approach would be to use the Indian model as an example and to establish an African Council of Agricultural Research, which would be tasked with the coordination of R&D activities across the continent. The objectives of this research would be two-fold: raise yields in Africa to world levels, and support the adaptation of agriculture in the face of climate change. The first project would be to create five R&D centers of excellence in Southern, Central, East, West, and North Africa. The Council could be financed by contributions from African Union member states and by partner funding.

Food-price shocks have significant impacts on countries’ balance of payments, especially since so many African countries rely heavily on food imports. That is why the AFREXIMBANK put in place a Food Emergency Contingent Financing Facility, which is a stand-by facility to finance commercial imports of food staples in times of crisis. The facility offers two products. The first product is a stand-by letter of credit, which is drawn on the basis of certain trigger events affecting the country’s food security. The second product is a food emergency reserve account through which vulnerable countries are encouraged to build reserve funds to be used when a food emergency occurs.

The idea of an African institution putting in place a special financing facility to help vulnerable African countries deal with food security shocks is very attractive and should be supported. It is not clear whether this facility has sufficient funds, and how many countries are opting to use it. An effort to mobilize resources from African countries and the international community may be needed to ensure that the facility has sufficient funding, and is able to offer attractive terms.

Concluding Remarks: the Importance of Peace and Stability

I have argued that a pan-African initiative for food security is needed. Such an initiative, which will complement individual country efforts, would include five elements: free trade in food commodities between African countries; regional investments in irrigation and other infrastructure to create African ‘bread baskets’; public-private partnerships to expand fertilizer production in Africa; creation of African agricultural R&D centers of excellence; and working with the AFREXIMBANK to ensure that vulnerable African countries have access to financing to import food during crises.

The data presented here shows a very high correlation between fragility, conflict, and food insecurity. Conflicts and instability affect many regions of Africa today: the Horn, the Sahel, Libya, Northern Nigeria, and Eastern DRC. The lives of millions of people are impacted, and hunger is rising because of the conflicts. Therefore, the top priority for African leaders should be to work towards resolving those conflicts and establishing the peace and stability that are the preconditions for food security.

References

- AGRA (2022) “Food Security Monitor: July 2022.” Nairobi. AGRA.

- FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO (2022) “The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022: Repurposing Food and Agricultural Policies to Make Healthy Diets More Affordable”. Rome. FAO.

- IMF (2022a) “Regional Economic Outlook, Sub-Saharan Africa: Living on the Edge.” Washington DC. IMF.

- IMF (2022b) “Regional Economic Outlook Analytical Note: Building a More Food-Secure Sub-Saharan Africa.” Washington DC. IMF.

- Suri, T. and C. Udry (2022) “Agricultural Technology in Africa” Journal of Economic Perspectives; Volume 36, Number 1, pp 33-56.

- The World Bank (2022a) “Africa Pulse: Food System Opportunities in a Turbulent Time.” Washington DC. The World Bank.

- The World Bank (2022b) “Food Security Update: October 13, 2022.” Washington DC. The World Bank.

- WFP and FAO (2022) “Hunger Hotspots: FAO-WFP Early Warnings on Acute Food Insecurity, October 2022 to January 2023 Outlook.” Rome. WFP.