Publications /

Opinion

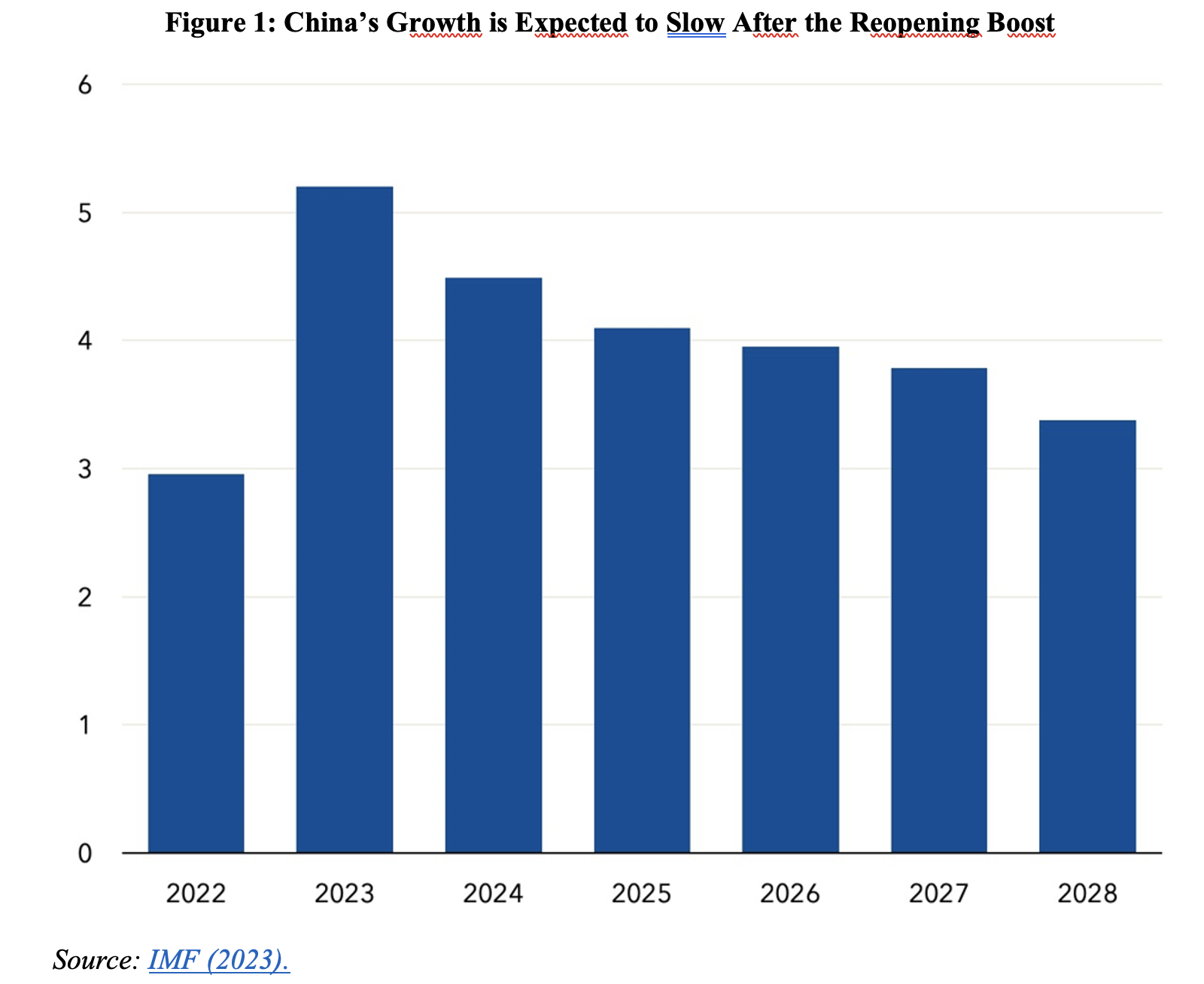

China’s rate of economic growth has slowed. Chinese GDP ended 2022 up 3%, but this was the lowest growth rate in the last 40 years, except for 2020, the first year of the pandemic. In addition to problems in its real-estate sector, China’s severe ‘COVID zero’ confinement policy is one of the causes.

The post-‘COVID zero’ reopening of the Chinese economy has improved its growth outlook. In the International Monetary Fund’s annual report on China, published in early February 2023, 5.2% growth in the country's GDP is projected for 2023, with this annual rate then declining to 3.5% in 2028 (Figure 1).

In addition to the inevitable uncertainty about the evolution of the pandemic, the IMF highlighted the contraction in the real-estate sector and the financial fragility of developers as risks that hang over the baseline scenario for China. It is enough to remember how important the real-estate sector was—along with investments in infrastructure—in smoothing the drop in the pace of growth during the Chinese economic ‘rebalancing’ in the period after the global financial crisis.

The IMF report points to the decline in the workforce and a slower pace of productivity growth as explanatory factors for a ‘new normal’ of slower Chinese growth after the pandemic. The easier growth gains from structural change in the workforce from agriculture to manufacturing, as seen during the decades of double-digit growth, are relatively exhausted, as is the boostobtained from excessive investments in infrastructure and housing in the second decade of the new millennium.

The IMF suggests reforms that would reinforce the weight of domestic consumption in demand, by strengthening the social protection system, for example through unemployment benefits and health insurance. It also notes that a gradual rise in the retirement age could increase the available workforce. Additionally, it mentions the productivity gains that would result from reform of state-owned companies that lag their private counterparts in terms of productivity. This last point about the desirability of a ‘rebalancing’ between the public and private sectors was made by former President Hu Jintao, and heard by myself at a ceremony in December 2011...

What are the implications for the rest of the world? After all, the IMF estimates that one percentage point of expansion in the Chinese economy today has an effect on other countries of 0.3 percentage points. For a large portion of Latin America, the impact is even greater, given the significance of Chinese trade for countries in the region, both directly and indirectly via the effects of Chinese growth on prices and traded quantities of commodities.

Currently, China consumes more than 16% of the world's oil, more than half of the copper, and more than 60% of the iron ore. Chile sends 67% of its copper exports to China, while Brazil sends 70% of its soybean exports there.

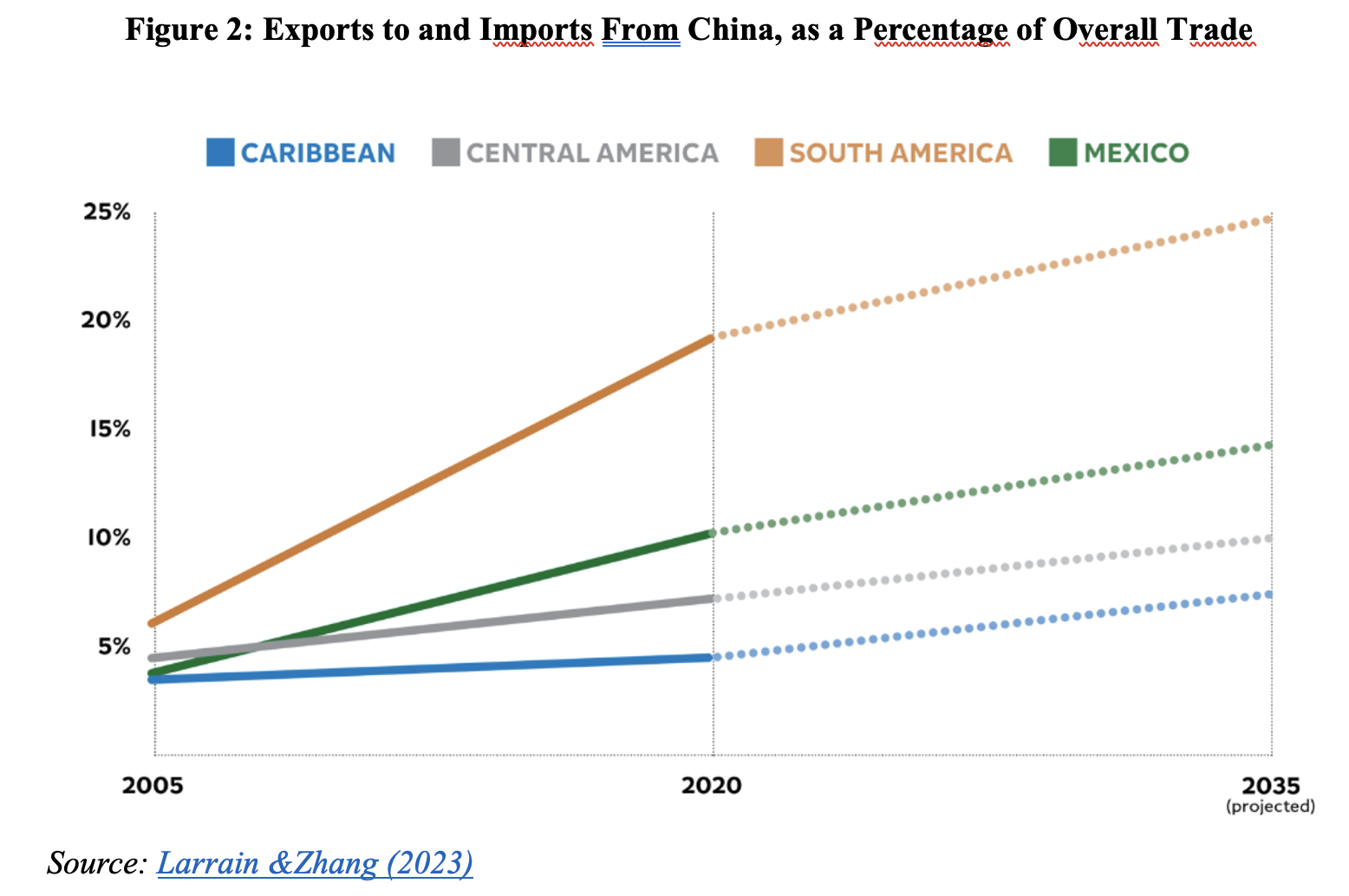

Foreign trade between Latin America and China rose from $12 billion in 2000 to $450 billion in 2021, when China was responsible for 18% of Latin American trade, against 5% in 2005. When Mexico is taken out, the Chinese share in 2021 rises to 24%.

The United States remains the main trading partner for Mexico and Central America, while China has taken over this position for South America. Brazil, Chile, and Peru have trade surpluses with China, with the latter absorbing more than 30% of Brazilian exports and almost 40% of Chilean ones.

Commodity demand driven by Chinese industrialization and the corresponding supercycle of commodity prices, boosted South America’s growth substantially in the decade from 2002 to 2012, with China remaining a major market for the region since. Naturally, the question now arises: will economic reopening and Chinese growth be strong enough to repeat that contribution via exports of food, minerals, and oil?

This time it will be more gradual and in a different direction. Not just in the slower pace of expansion (Figure 2), but in composition. The Chinese ‘rebalancing’ will continue towards services and products higher up the technological scale of value chains, with an emphasis on electric vehicles and renewable energy. Imports and investment priorities abroad will accompany this evolution.

In relative terms, oil will fall, and critical metals and minerals will rise: aluminum, lithium, copper, etc. As elsewhere, China’s energy transition will be reflected in the composition of its imports.

We have witnessed a reconfiguration of China's financial and investment operations in Latin America and the Caribbean. The era of massive loans from official Chinese banks to support the production of raw materials in the region—more than $138 billion between 2005 and 2020—seems to be over. Back in 2019, we already remarked how the speed and intensity of China’s growth-cum-structural-change was to a large extent matched by the profile and volume of its capital flows to Latin America over the previous years. The official lending gap was filled in small part by other banks and private equity funds.

In the beginning, the extractive industry—oil and gas, copper, and iron ore—received the bulk of the resources, while more than half passed to service sectors, to domestic supply in areas such as transport, finance, electricity generation and transmission, information and communication technologies, and to alternative energy supply. With this new configuration, foreign direct investment flows into Latin America and the Caribbean have remained solid at levels above $4.5 billion as an annual average since 2016, according to estimates by Larraín and Zhang (2023).

Hovering over this Chinese presence in local investments, there is what some have already called the “new cold war” between the United States and China. Changes in the geopolitical environment after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the intensification of the United States-China rivalry should have consequences on the relationship between China and Latin America. Meanwhile, the ‘new normal’ in post-pandemic Chinese economic growth will have distinctly different impacts from the previous period.