Publications /

Policy Brief

Since its inception, the African Union (AU) financial structure has been heavily reliant on funding from international partners, which many believe has weakened its autonomy and ability to act independently towards pursuing its own agenda 2063 to promote unity, peace and sustainable development across the continent in a manner that truly reflects the priorities of its 55 member states. In 2024, the reality is still not different despite recent momentum as the union’s approved budget shows that 62% will be financed by external donors.

The paper briefly looks at the history of the AU’s self-financing efforts and progress made since the adoption of the financial reforms in 2017, also known as the Kigali decision, that saw an introduction of the 0.2% import levy. These reforms, if implemented effectively, aim to address the challenge of member states’ inconsistent compliance in payment of annual contributions, the lack of diversified revenue sources and inefficient financial management practices. By 2018, 25 countries out of the 55 member states were at various stages of implementing the Kigali decision, with 16 of these countries already collecting the levy by 2020 and 31 members (over 50%) having paid their full annual contributions to the union by 2023.

The reforms present both challenges and opportunities that the paper highlights including lessons that can be drawn from regional bodies such as the Economic Commission of West African States (ECOWAS) which has demonstrated that with the right leadership, financial autonomy using a similar levy is possible for the AU. It concludes by emphasizing that strong political will and joint efforts from member states, partners and internally within the AU is crucial for the reforms to be effective to realize the AU’s vision to become an independent organization capable of driving its own development agenda.

Introduction

In 2017, the African Union (AU) embarked on an ambitious self-financing mission for its operations, stemming from a historic decision adopted by Heads of State and Government (HSG) the previous year, during a ‘Retreat on Financing of the Union’ at the 27th AU Summit in Kigali, Rwanda. The decision responded to mounting calls for financial reform within the institution, which were starting to grow louder, and the increasing criticism of its lack of financial transparency and accountability, which had undermined trust in the organization.

This decision was not the first attempt at self-financing for the AU. According to Mehari Maru the AU began its search for alternative financing in 2005 through a high-level panel led by former President of Senegal Abdoulaye Wade. The panel recommended a 20% levy on imports coming from outside the AU member states, but it was not approved because of a need for further studies and research. In 2011, in a second attempt, the AU established a high-level panel led by former president of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, Olusegun Obasanjo. Its findings (African Union, 2013)were presented to the AU in 2013, proposing a $2 hospitality levy per hotel stay and a $10 airfare levy on tickets for flights originating from Africa or with destinations in Africa. The collection of revenues from the latter was to be effected in collaboration with the International Air Transport Association (IATA) and relevant transport agencies, while the former was to be collected in close collaboration with the ministries in charge of tourism in respective member states. A separate account of resources collected from the two taxes was to be opened at member-state central banks. Although this proposal was tabled and adopted, it was not implemented and was eventually discarded after concerns were raised by member states with economies heavily reliant on tourism.

By 2017, 2 subsequent events had brought about a new momentum that revitalized the self-financing efforts: 1) The appointment of Dr. Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma to the position of Chairperson for the African Union Commission (AUC) in 2012; her outspoken ambition was to increase member states’ contributions to reduce the high degree of dependency on donors (Pharatlhatlhe & Vanheukelom, 2019); 2) the 2015 financial crisis that hit the AU, resulting from a myriad of circumstances including insufficient and delayed member-state contributions, a temporary halting of donor funding resulting from the findings of a critical external audit of the AUC’s finance management systems, and a shifting of aid to other funding priorities (African Union, 2015). Against the backdrop of these developments, the AU HSG convened in Johannesburg, South Africa, where they decided on a set of financing reforms to revise and scale-up assessment of member-states’ contributions, and explore alternative sources of funding from member states.

As the then newly-elected Chairperson of the AU (2018), President Paul Kagame hit the ground running in an effort to accelerate the implementation of the Kigali Decision by setting up a 9-member pan-African advisory committee, led by Dr. Donald Kaberuka, to come up with an actionable proposal for the AUs ongoing institutional reforms towards self-reliance and autonomy, recognizing the need for financial sustainability. The proposal, which was adopted by member states, introduced a 0.2% levy on all eligible imported goods into the continent. The contributions would be sufficient to cover 100% of the AU’s operational budget, with 75% going to the program budget and 25% towards peace support operations.

The newly adopted financial reforms were intended to achieve: a) timely, adequate, reliable, and predictable payments from both member states and partners; b) financial autonomy and reduced dependence on external sources; c) equitable burden-sharing of the AU’s budget and reduced dependence on a few countries; d) improved budget, financial oversight, and governance to achieve high fiduciary standards, value for money and probity; e) predictable and sustainable financing of the AU’s peace operations through the revitalization of the AU Peace Fund (APF) and the pursuit of strategic partnerships. In 2024, Nana Akufo-Addo, the President of the Republic of Ghana was appointed as the AU champion for the reforms, taking over from Kagame to complete what was started in 2017 (African Union, 2024).

This paper seeks to start a conversation by arguing that only through financial sovereignty can the AU be autonomous and fully realize the aspirations of its founding fathers through its continental Agenda 2063, towards an integrated, prosperous, and peaceful Africa. It examines the historical background to these efforts (partly explored in part 1, introduction), the current financial situation, proposed reforms and their implications. The paper is therefore organized as follows: section 2 provides an overview of the current financial situation of the AU. Section 3 covers some of the challenges and opportunities the reforms present, touching on similar undertakings to draw lessons. Section 4 looks at some implications to consider and then concludes.

Overview of Current Financial Situation

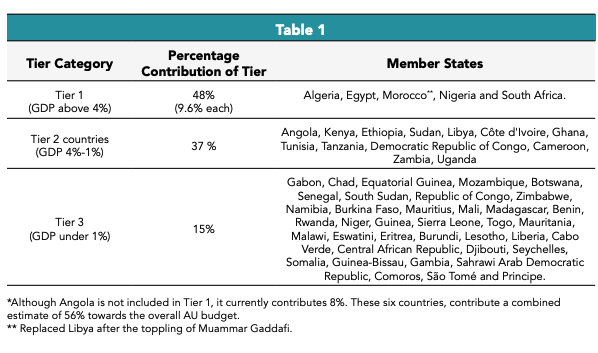

The AU’s financial budget is made up of contributions from member states (briefly explained below) and funding from international partners (external donors). Member states contributions are categorized based on a 3-tier assessment system according to a country’s share of continental GDP (i.e. the biggest economies contribute larger shares to the budget).

According to the Institute for Security Studies, the total approved budget for 2021 was $623,836,163, of which $203,500,000 (32%) was to be financed by member-state contributions, and $406,194,344 (65%) by external partners. A total of $605,756,610 has been approved for the 2024 AU budget, of which $370,080,331 (62%) is to be financed by external donors, and $200,000,000 (33%) is to be financed by member states.

Based on these numbers (both previous and current) over half of the budget is still being financed by international partners, which some critics have said comes with strings attached as some external donors often earmark their contributions for specific programs or projects (Pharatlhatlhe & Vanheukelom, 2019), imposing conditionalities and priorities that may not align with the AU's own objectives might place the organization in a position where in order to receive such funds, it has to comply and tailor its objectives to align with those of donors. In this case, it can be argued that, it is the international partners that drive the agenda of the AU, which may not always and necessarily be in the interests of Africa and Africans. To address this criticism, it is important to highlight that, as of 2010, a core group of about 10 donors found some common ground with the AUC to partner in joint programming and joint financing to harmonize their aid funding and align it with AUC priorities and management systems. These efforts are part of a partnerships framework that attempts to seek ‘action-oriented partnerships’ so as not to accept just ‘any’ money, but money that can allow for meaningful engagement with donors on the AU’s priorities, taking into account member-state interests (Apiko, 2021)

To reinforce implementation of the financial reforms including the 0.2% levy, a few complementary actions were taken;

- A committee of 10 finance ministers (F10) was established, later expanded to 15 (F15). The committee was given the mandate of providing overall budget oversight.

- In 2018, 9 ‘Golden Rules’ were adopted and put into place for proper management of the AU’s finances, 8 of which are currently fully operational.

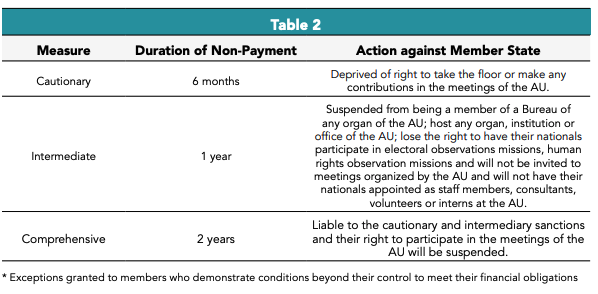

- A strengthened sanctions regime for non-payment of contributions was adopted to encourage compliance to address the long-standing criticism of failure to take disciplinary action against member states that default on payments. The measures put in place are as follows:

Milestones Achieved

- As of December 2018, 25 countries, representing about 45% of AU member states, were at various stages of implementing the Kigali Decision on Financing the Union. Of the 25 member states, 16 countries are collecting the levy on eligible imports (African Union, 2020).

- The sanctions regime for non-payment of assessed contributions has so far yielded some positive results. 3 out of 4 countries that had previously been put on payment plans due to failure to pay on time, hadcleared their arrears by February 2022.

- The following member states have been put under sanctions;

- Cautionary sanctions: Sao Tome and Principe, Guinea, and Congo.

- Intermediate sanctions: South Sudan.

- The AU Peace Fund (APF) governance structures are fully operational, and $384 million has been raised—96% of the initial target of $400 million—entirely from AU member states (Kinkoh, 2024).

- To address the issue of skills/capacity gap of the AUC, a merit-based recruitment system was introduced, and all departments underwent a skills audit and competency assessment.

- The AU has also introduced budget ceilings for departments to make the organization leaner through budget execution, ultimately ensuring expenditure is linked to results. The ceiling also aligns the budget of the Union with the capacity of member states to pay.

It is important to note however, that some member states, mainly the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) bloc of countries, took a political stance against the 0.2% levy (Chekol, 2020), but nevertheless committed to honor the principle of ‘obligation to pay’ through alternative means, in line with the spirit of the financing of the Union. This is based on the flexibility embedded in the Kigali Decision for member states to determine the appropriate form and means they will use to meet their financial obligations, with some opting to implement the levy and others expressing their intention to continue paying using the current annual assessment arrangement (African Union, 2020).

Challenges and Opportunities

According to the AU, annually, over half of its member states fail to pay their financial contributions towards the yearly budget on time, hampering the planning, implementation and execution of programs and activities. The following highlights both the challenges to be overcome and the opportunities to be seized to ensure successful implementation of the financial reforms.

Opportunities

- Increased Ownership and Autonomy

The 0.2% import levy offers an alternative source of revenue for member states to meet financial obligations, as highlighted above with success stories of countries that have managed clear their arrears with the AU. This a great opportunity for the AU to assert greater ownership and autonomy over its agenda, free from dependence, pressure, and conditionalities, and ultimately to enhance the organization's credibility and legitimacy.

- Enhanced Efficiency and Effectiveness

The 0.2% levy mechanism is easy to implement as it is not subject to time-consuming budgetary procedures and parliamentary approval by member states. This allows for efficient streamlining of administrative processes and overall improvement of financial management practices.

- Diversification of Revenue Sources

Because the 0.2% levy gives discretion to member states to use excess revenue collected to meet either their domestic or international commitments, it opens up new opportunities for financial sustainability and resource mobilization. This will allow for leveraging partnerships with regional financial institutions, development banks, and the private sector, to unlock further additional funding for AU initiatives.

- Strengthened Regional Integration

Some critics have previously argued that the AU is a little too far from home for many African countries to see the benefits of membership, compared to their own regional economic communities (RECs), which generally have greater success in collecting members states’ dues (Fabricius, 2015). These RECs - ECOWAS, CEMAC, and EAC have successfully implemented similar levies to fund their activities, respectively at 0.5%, 0.05%, and 1.5%. Further, On January 1, 2021, trading commenced under the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). 54 member states of the AU agreed to establish the free-trade zone, theoretically the largest in the world (International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2021). The AfCFTA aims to create a single market for goods and services across Africa, promoting regional integration and economic growth. It is projected to contribute about $450 billion to Africa’s overall GDP by 2025. Further unlocking additional revenue sources for member states (as they trade easily with each other across borders) will allow them to honor their commitments to make contributions, and bring the member states closer to the AU.

Strong Global Advocacy and Influence

More financial independence and autonomy will enable the AU to advocate more effectively for African interests on the global stage and to assert its influence and credibility by demonstrating fiscal responsibility and self-reliance. The financial reforms are complemented by the recent launch of the Alliance of African Multilateral Financial Institutions (AAMFI) -also known as the Africa Club’ - as a strategic platform for coordination, engagement, and advocacy with a view to increasing Africa’s power in the global financial system, by bringing member institutions together to find solutions to financing challenges for member states on the continent. This move seeks to introduce innovative financial instruments and provide an avenue for the major concern of debt management for African countries. The AU being admitted as a full member of the G21 - previously G20, has also raised its prominence and visibility, which many, including the United Nations (UN) have applauded as a reflection of Africa’s growing influence and importance on the global stage.

Challenges

- Member State Compliance

As of October 2023, only 31 out of 55 members had paid all of their annual contributions, leaving a gap of $56.3 million and diminishing ownership of AU programs and its financial autonomy (Kinkoh, 2024). Currently, only 16 member states are collecting revenue from the levy, and although funds are being collected, they are not always remitted in full (African Union, 2019), as the current enforcement mechanism is not strong enough to ensure that the money collected is actually transmitted.

Because of national, economic, and legal constraints, and international commitments, some countries are not able to implement the 0.2% levy. Countries such as Seychelles and Mauritius have undertaken a zero-tariff commitment at the World Trade Organization (WTO) on almost 95% of their imports, hence imposing the 0.2% levy on the remaining goods would yield less than what is required to pay to AU. Similarly, doing so would be in breach of GATT Article II on schedules of commitments. Other member states, such as the Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic, do not have a tangible productive industry or export sector. Their imports, mostly for humanitarian purposes are for sustaining their refugee status, they are constrained by legal limits under their obligations to the WTO, especially in respect of the most-favored nation (MFN) principle. These financial obligations pose a significant challenge for the said member states.

- Political Will

Securing political buy-in and commitment from AU member states for financial reforms may be challenging because of competing political priorities and interests. For example, a number of small island states (SIS) have raised concerns that their economies are too small and undiversified, depending mainly on tourism. These countries have indicated that an increase in the tariffs on the small quantity of imports they receive could potentially weaken their economies.

The lack of political will of member states to implement adopted decisions has been a weakness of the AU for a long time - an issue reiterated by H.E. Moussa Faki Mahamat during the last summit, as he serves his final year as the AUC chairperson. In a stern speech, he noted the tendency of HSG to make decisions without real political will to implement them, highlighting that over the last 3 years, 93% of decisions have not been implemented. This challenge is grounded in the fact that the AU still remains largely an intergovernmental organization, compared to a supranational body like the European Union (EU), which has binding powers over its member states.

- Debt Financing

According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), African countries’ total debt stands at over $1.8 trillion, and more than half of these countries are currently spending a significant amount of their national budgets on servicing their external debts than funding critical sectors such as healthcare, education and infrastructure. The debts amounted to $85billion in 2023. In December 2023, Ethiopia became the third African country after Zambia and Ghana to default on servicing its debt. Such severe debt distress means these countries are having difficulties in meeting their obligations. This has triggered calls to find solutions to payment difficulties experienced by African debtor countries.

- Dependency on External Funding & Bureaucracy

Given the AU's historical reliance on international partners, ensuring a smooth transition to self-reliance while mitigating potential funding gaps will require careful planning and strategic coordination. This will require capacity building to close any skills gaps, and to challenge any resistance that may stem from entrenched longstanding interests or bureaucracy, in order to ensure effective financial management and independence of the AU.

Addressing these challenges and seizing the opportunities presented by financial reform will require collective joint efforts from the AU, its member states, and external partners to realize its vision of autonomy. Realizing this, in his first act as the newly elected AU chairperson, President Nana Akufo-Addo proposed that an Annual Economic Summit should be convened as a platform to review and accelerate actions towards financial independence, further calling on member states to ratify instruments supporting the establishment of the AU financial institutions (African Union, 2024). These reforms should propel Africa to take steps towards greater impact in financing itself as a continental institution.

Lessons to be Learned From ECOWAS

As (Osula, 2017) argues, self-financing is not new to Africa, and the AU could learn a lot from one of its RECs - ECOWAS. This has already successfully implemented a similar import levy of 0.5% (previously mentioned) to finance its commission, which shows that it can be done (Louw-Vaudran, 2016). ECOWAS has often been praised as a good example of a well-functioning regional body, not just in terms of ensuring financial compliance by member states, but in its inclusive approach that promotes the engagement of a wide range of actors within the region, having demonstrated strong political leadership and will in its conflict prevention and peacebuilding efforts (Osula, 2017).

Implications and Conclusions

As discussed throughout this paper, the AU's current over-dependence on external funding poses significant implications for its autonomy, and sovereignty over its own agenda. It undermines the organization's ability to pursue its own strategic objectives and assert its authority on the global stage. By relying on partners to finance its operations, the AU risks compromising its integrity, credibility, and legitimacy as a continental institution.

While member states have committed to make annual assessed contributions to the AU budget, their compliance has varied in the past, leading to inconsistencies and gaps in funding, with consequences for the efficient running of the union. Such delays in payments and arrears hinder its ability to plan and implement programs effectively. The AU’s financial management practices have also been marred by a lack of transparency and accountability, exacerbating concerns about mismanagement and skills capacity. Although successfully implementing the financial reforms presents opportunities to enhance sustainable revenue generation, improve financial management practices, strengthen regional integration, and reduce dependency on donors, it also poses certain challenges stemming from entrenched bureaucracy, lack of political will in certain instances, and lack of enforcement mechanisms to ensure member states’ compliance.

The 0.2% levy presents an alternative avenue for a more reliable and consistent source of funding from member states. By reducing dependence on external donor funds and pursuing action-oriented partnerships through joint programming and joint financing that harmonizes partner funding, to align with the priorities and management systems of the AUC, the AU will demonstrate fiscal responsibility and be better positioned to pursue an independent agenda that reflects the interests and priorities of its member states and people, with the support of external donors.

The importance of political will cannot be emphasized enough as it is crucial for success. Lessons can be learned from ECOWAS on how strong political will and leadership, as well as self-financing efforts through the similar undertaking of implementing an import levy, can yield positive results towards promoting timely payment by members of their contributions. Additionally, imposing strict penalties on non-complying member states will allow for greater accountability and successful implementation of the reforms. Finally, a strengthened internal audit and oversight mechanisms through the committee of 15 finance ministers (F15) could go a long way in ensuring compliance to realize the ultimate vision of African self-reliance and autonomy.

References

- African Union. (2013). Report of H.E. Mr. Olusegun Obasanjo, Former President of Nigeria, Chairperson of the High-Level Panel on Alternative Sources of funding the African Union. Retrieved April 27, 2024

- African Union. (2015). Decisions, Declaratiion and Resolutions. Retrieved May 1, 2024

- African Union. (2019). Status and Proress Report on Financing of the Union. Retrieved April 29, 2024

- African Union. (2020). Financing the Union Status Report - An Update. Retrieved April 27, 2024

- African Union. (2024). Africa seeks a new financial landscape to address debt, risk ratings and cost of capital. Retrieved April 25, 2014, from https://au.int/en/pressreleases/20240217/africa-seeks-new-financial-landscape-address-debt-risk-ratings-and-cost

- Apiko, P. (2021). Getting partnerships right: The case for an AU strategy.

- Augustine, C. (2024). African Continental Free Trade Area. Retrieved May 1, 2024, from South African Government GCIS: https://www.gov.za/blog/african-continental-free-trade-area-0

- Chekol, Y. G. (2020). African Union Institutional Reform: Rationales, Challenges and Prospects. Sage, 39-40. Retrieved May 2, 2024

- Fabricius, P. (2015). The AU starts to put its money (closer to) where its mouth is. Retrieved April 25, 2024, from Institute for Security Studies: https://issafrica.org/iss-today/the-au-starts-to-put-its-money-closer-to-where-its-mouth-is

- Good Governance Africa. (2017). The AU’s funding woes continue. Retrieved from https://gga.org/the-aus-funding-woes-continue/

- Institute for Security Studies. (2021). AU financial independence: still a long way to go. Retrieved April 26, 2024, from https://issafrica.org/pscreport/psc-insights/au-financial-independence-still-a-long-way-to-go

- International Institute for Strategic Studies. (2021). The launch of the African Continental Free Trade Area. Retrieved May 1, 2024, from https://www.iiss.org/sv/publications/strategic-comments/2021/the-launch-of-the-african-continental--free-trade-area/

- Kinkoh, H. (2024). A new champion could drive home African Union reforms. Retrieved May 2, 2024, from Instituute for Security Studies: https://issafrica.org/iss-today/a-new-champion-could-drive-home-african-union-reforms

- Louw-Vaudran, L. (2016). A new financing model for the AU: will it work? Retrieved May 5, 2024, from https://issafrica.org/author/liesl-louw-vaudran

- Osula, M. (2017). The African Union’s road to financial independence: Pragmatic or ideological? Retrieved May 5, 2024, from Uppsala University: https://www.sipri.org/commentary/blog/2017/african-unions-road-financial-independence-pragmatic-or-ideological

- Pharatlhatlhe, K., & Vanheukelom, J. (2019). Financing the African Union - On mindsets and money. Retrieved April 26, 2024

- Staeger, U. (2022). Analysis of African Union decisions from February 2022: Wicked challenges in AU funding and reform, but an increasing commitment to paying up on time. Retrieved May 7, 2024, from https://uelistaeger.wordpress.com/