Publications /

Opinion

A slowdown in China and winding down of U.S. stimulus threaten a much-needed regional rebound.

First appeared at Americas Quarterly

The last year has seen some good news for Latin American economies. The region’s recovery has been stronger than expected, and growth forecasts by the World Bank and IMF have improved since six months ago. Vaccination campaigns and fiscal support have sparked an economic rebound since the second half of last year, despite an apparent loss of momentum in the third quarter of this year.

But the future looks uncertain. Latin America is caught between two major global forces that threaten the region’s growth: a potential drop in capital flows from the U.S. as pandemic stimulus tapers off; and decreasing growth in China, where an energy crunch is hitting just as the country’s exhausted property markets begin to go into reverse. To weather the storm, countries in the region will have to target their fiscal support and signal that medium-term frameworks will be followed, while doing what it takes to ensure a private-sector recovery can compensate for policy contraction.

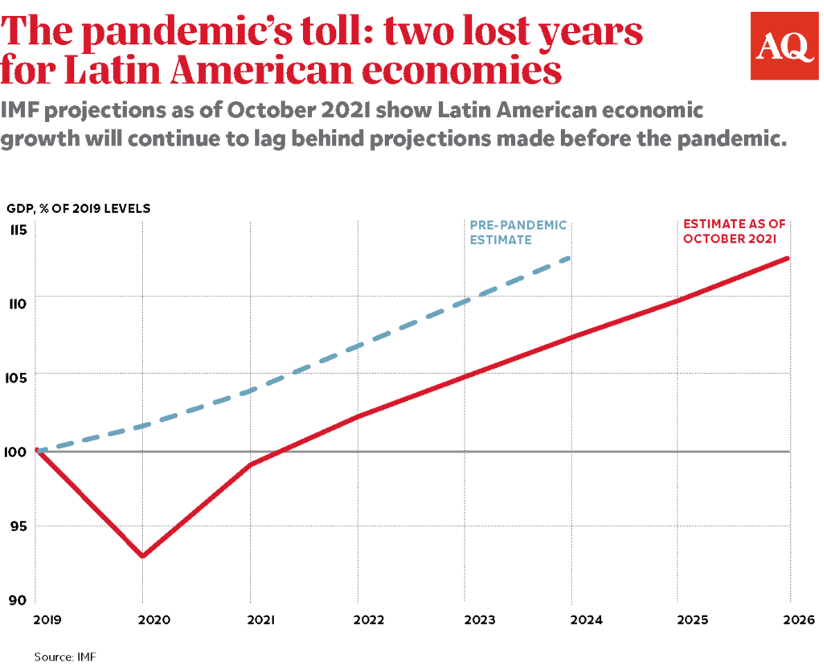

Even up to this point, the region’s recovery has been uneven and partial. This has been due in large part to differences in vaccination rates — 75% of the population fully vaccinated in Uruguay, 5% in Nicaragua — and in ability and willingness to deliver fiscal support. By the end of this year, the GDP of most countries in the region is set to remain below 2019 levels, and no country is likely to reach the GDP levels forecasted for 2022 prior to the pandemic.

The recovery has been thanks in part to the strength of GDP growth in the region’s biggest trading partners — the U.S., China, and Europe — as global financial conditions remained positive despite occasional hiccups. A commodities resurgence has recently cooled, as prices of some commodity groups have fallen or held steady, but terms of trade have improved overall for commodity-dependent countries in the region. According to the tracking by the Institute of International Finance (IIF), capital flows to Latin America rebounded this year, slowing down in the second half.

But the global landscape looks set to become more hostile, as trends in both the U.S. and China are set to make things difficult for Latin American economies. A global uptick in inflation, reflecting supply restrictions and labor constraints unlikely to resolve in the immediate future, makes interest rates hikes and an end to monetary stimulus likely for next year. Since late September, investor concerns about U.S. inflationary pressures have pushed up yields, reversing a decline in market interest rates.

Some fear that changing monetary policy in the U.S. could spark a rerun of the 2013 Taper Tantrum, when capital fled emerging markets. But capital flows to the region have not been as intense in the last few years. For most countries, favorable terms of trade and depressed domestic demand have led to reasonably comfortable external accounts. A repeat of 2013 seems unlikely, but domestic investment could drop if financial conditions worsen.

Meanwhile, China — top buyer for much of Latin America’s exports — is facing growth deceleration as its property markets’ GDP-boosting activity stalls, in a rerun of its economic rebalancing after the financial crisis of 2008. The direct impact of the collapse of Evergrande, a heavily indebted Chinese real-estate company, and other property firms may remain mostly domestically confined, but the resulting macroeconomic slowdown has already appeared in the latest figures. China’s new growth pace may exact a toll both on exports and commodity terms of trade for the region.

Latin American countries can do little to alter these global trends. How can they best navigate them? The best option may be simply to concentrate on the domestic front. The pandemic’s legacy of higher public debt means fiscal and financial support must become more selective, focusing on the most vulnerable firms and workers. Countries in the region that typically face narrow fiscal space (Brazil, Colombia, and to some degree Mexico) will shun new spending. Those still in a more favorable territory, such as Chile and Peru, must still anticipate tighter external financial conditions ahead.

Limited policy space and social pressures exacerbate political risks, but rolling back spending means relying heavily on the private sector to drive recovery. The recent experiences of Mexico and Peru have illustrated how policy uncertainty may restrain private investment. The region will have to rely on higher efficiency, spending less while making sure money goes to help the segments of the population most negatively impacted by the pandemic crisis.

On a longer-term horizon, attention needs to be paid to the fact that incomplete economic recovery has generated weak labor markets, rife with scarring and “shadow” unemployment. Hence the relevance of implementing policies of retraining and reskilling workers. As Carlos Felipe Jaramillo, Pepe Zhang, and I have recently discussed, Latin America has already partly reached high-income status — but a substantial part of its population faces high vulnerability to economic shocks and natural disasters. The pandemic has made it painfully clear that the region badly needs a vulnerability-based approach to understanding and tackling poverty.

The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author.