Publications /

Opinion

Argentina’s peso tumbled and stocks plunged after last Sunday’s primary elections. The perception of a likely victory of President Macri’s opponents – Alberto Fernandez, and running mate, Christina Fernandez de Kirchner - has sparked a new shift in investor preferences away from peso assets, pressures on the exchange rate, and hikes on sovereign spreads.

Unless fears of a return to policies prevailing before Macri are assuaged, the market rout tends to deepen as a negative feedback loop happens between that preference shift and the underlying debt dynamics in Argentina. Gross financing needs ahead – before elections and next year - are high and, given the large share of public and corporate debt in foreign currency, the combination of asset dumping by investors and exchange rate depreciation has led credit default swaps on Tuesday to price in up to a 75% chance of a default in the next five years, while that likelihood was below 50% last Friday.

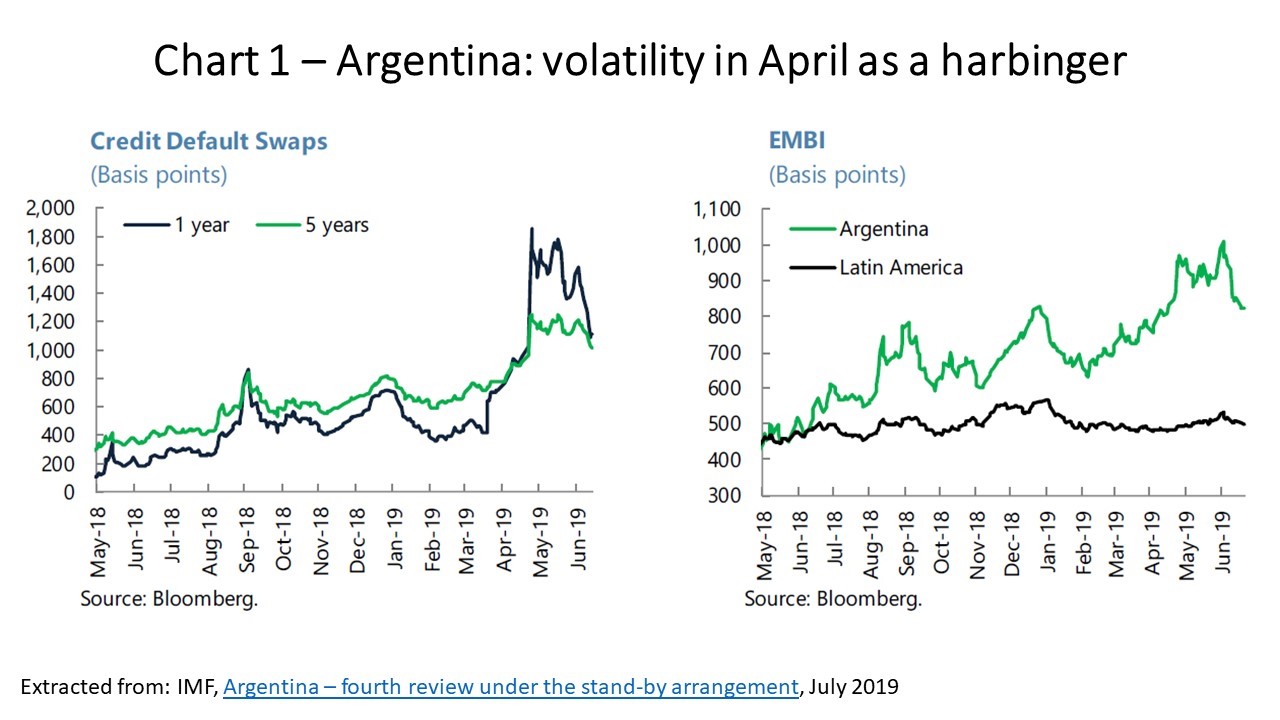

The market volatility and sell-off of Argentine assets in the last week of April was a harbinger. And even though financial markets stabilized in the following months, debt maturities have been shortened afterwards and short-term roll-over needs have soared, while sovereign spreads remained higher than before (Chart 1). Then the worst-case scenario from investors’ standpoint seems to have become the likeliest.

Immediate macroeconomic consequences tend to be harsh. Inflation, already running close to 60% a year, tends to hike as a result of the peso fall. The contraction in economic activity had moderated in the first half of the year, as the performance of agriculture, construction, and manufacturing partially outweighed the decline in services. Now, the inflationary impact downward on household real income, the seizure of bank credit to the private sector, and deteriorating labor market conditions will all take additional tolls on private consumption and growth.

How the current turmoil compares with the May storm of last year? Haven’t Argentina’s financial vulnerabilities diminished as witnessed by a revival of some enthusiasm and bond buying since then, especially after the package agreed with the IMF?

The answer is “not much”. The triggers of the current and last year’s episodes may be different. US interest rate hikes and dollar appreciation in the months prior to May 2018 were the culprits then, whereas domestic political developments have now been the major factor. Nonetheless, there was no fast-enough cure of the singular combination of low reserves adequacy and dollar-denominated debt displayed by Argentina that made it particularly vulnerable to retrenchment in capital flows then and now.

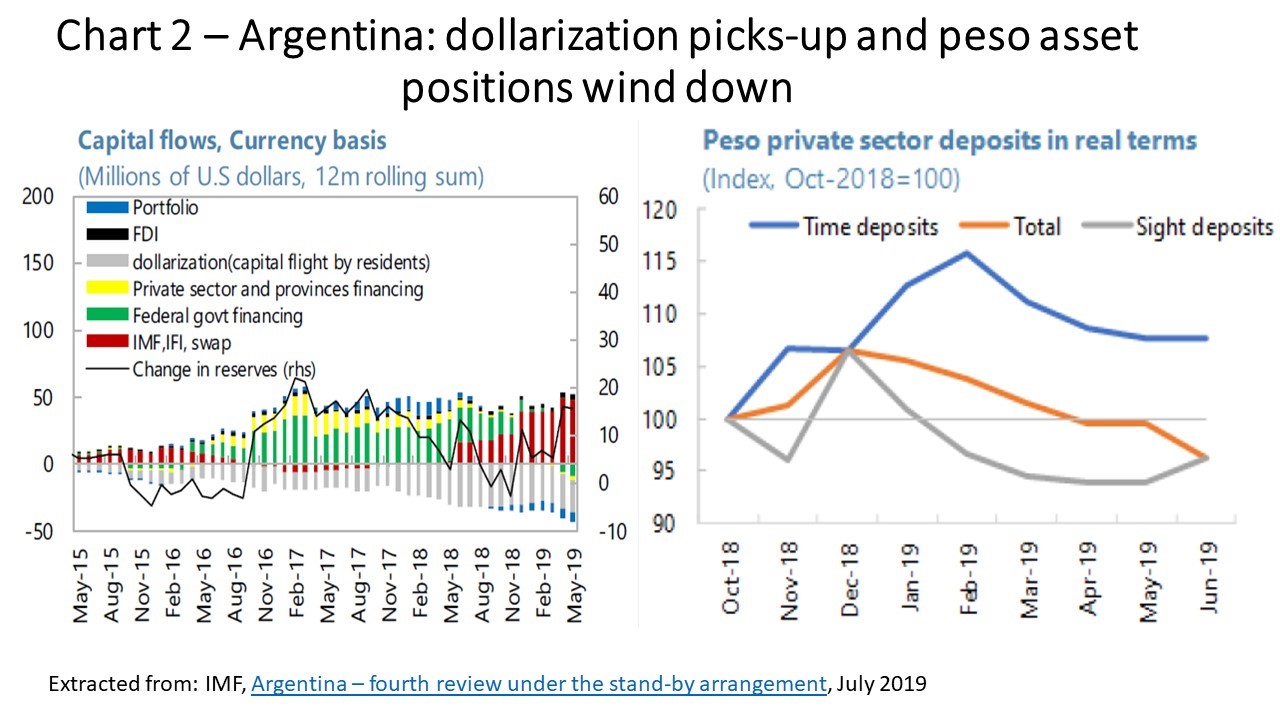

The IMF’s fourth review of its stand-by arrangement with Argentina, released last July, showed some improvement in Argentina’s both external sector and public debt sides, but with way still to go as far as overcoming those fragilities. It is remarkable how dollarization picked up from March onwards and portfolio investors kept on winding down their peso asset positions (Chart 2). Paradoxically, given the surge in capital inflows after the agreement, mostly bond purchases and not foreign direct investment, the new round of outflows may lead to a call for an addition of resources to the prevailing IMF package, the bulk of which will have already been disbursed by election day.

That leads us to the election blame game and what it entails for the future of economic policy in Argentina, as that may affect the unfolding of the current asset market rout. How much responsible should be held the current and previous government policies for where Argentina is now? Can main competitors do something to assuage current fears?

A double attribution of responsibility follows. On the one hand, Argentina’s vulnerabilities are a major legacy from the previous Kirchner era, when ad hoc public interventions, seizure of pension funds, data manipulation, fiscal deficits and rising inflation led to deep economic fragilities. On the other, instead of “neoliberal policies that failed”, President Macri’s “gradualism” in reducing fiscal deficits and inflation, including a leniency with the local currency overvaluation as a substitute to interest rate hikes, did not address those fragilities in time to ring-fence the economy from the global scenario changes of last year. Since then, while implementing the agreement with the IMF, the government has also resorted to unorthodox policy moves such as freezing utility tariffs, interest-free payment plans for consumer goods, discounts and subsidized loans, and others. Fact is that the Gross Domestic Product is lower, and unemployment, inflation, and public debt to GDP are all higher than when Macri took over.

From now until final elections, the primary winners of last Sunday may opt for minimizing risks of jeopardizing their edge, walking through sidelines and not addressing straight the economic issues at stake. President Macri, in turn, this Wednesday announced cuts in income taxes for workers, boosts on subsidies for social services, as well as a freeze on gasoline prices for 90 days.

The peso kept sliding downward after his announcement. Either because investors believe President Macri’s populist moves would be “too little, too late” to reverse the election landscape, because they fear bolder moves ahead, or it does not matter much. The most unlikely scenario is the one that would address market fears in the run-up to elections, namely, one in which both major candidates would state credible commitments with completion of Argentina’s adjustment.