Publications /

Policy Brief

Greater female participation in the labor market and in international trade have been recognized as important drivers for economic growth and essential targets in the context of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). However, achieving both targets simultaneously will be difficult, if not impossible, in most Middle East and North African (MENA) countries without additional policies to eliminate the remarkably high levels of gender inequality in the labor market.

In such countries, women are either excluded from the gains from trade or bear most of the burden of adjustment to greater integration in the global economy. Policymakers should recognize the impacts of greater integration into global trade on women’s labor-market outcomes, and should implement resolute policy measures to alleviate (if not eliminate) these impacts.

THE MENA GENDER-EQUALITY PARADOX

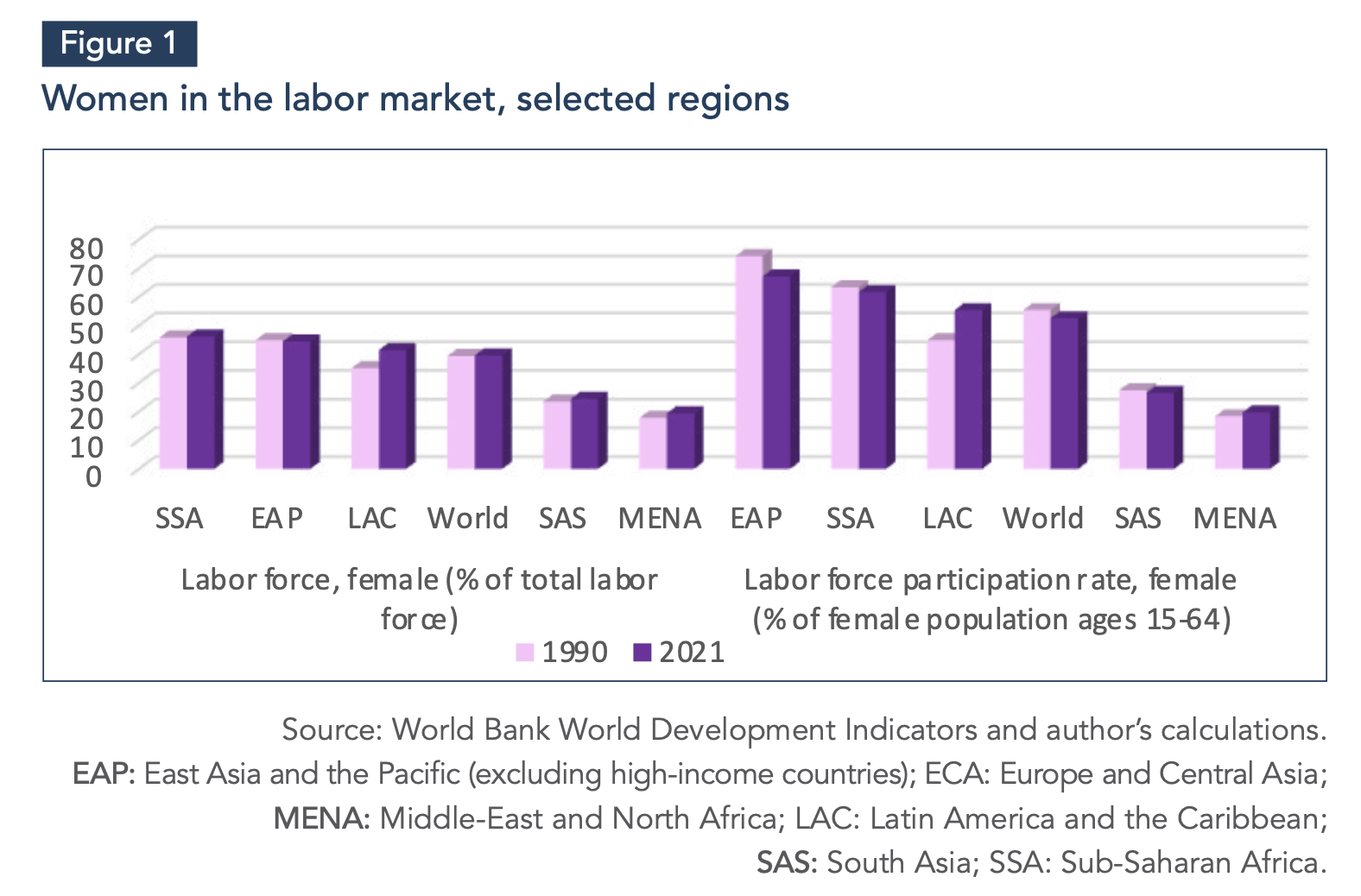

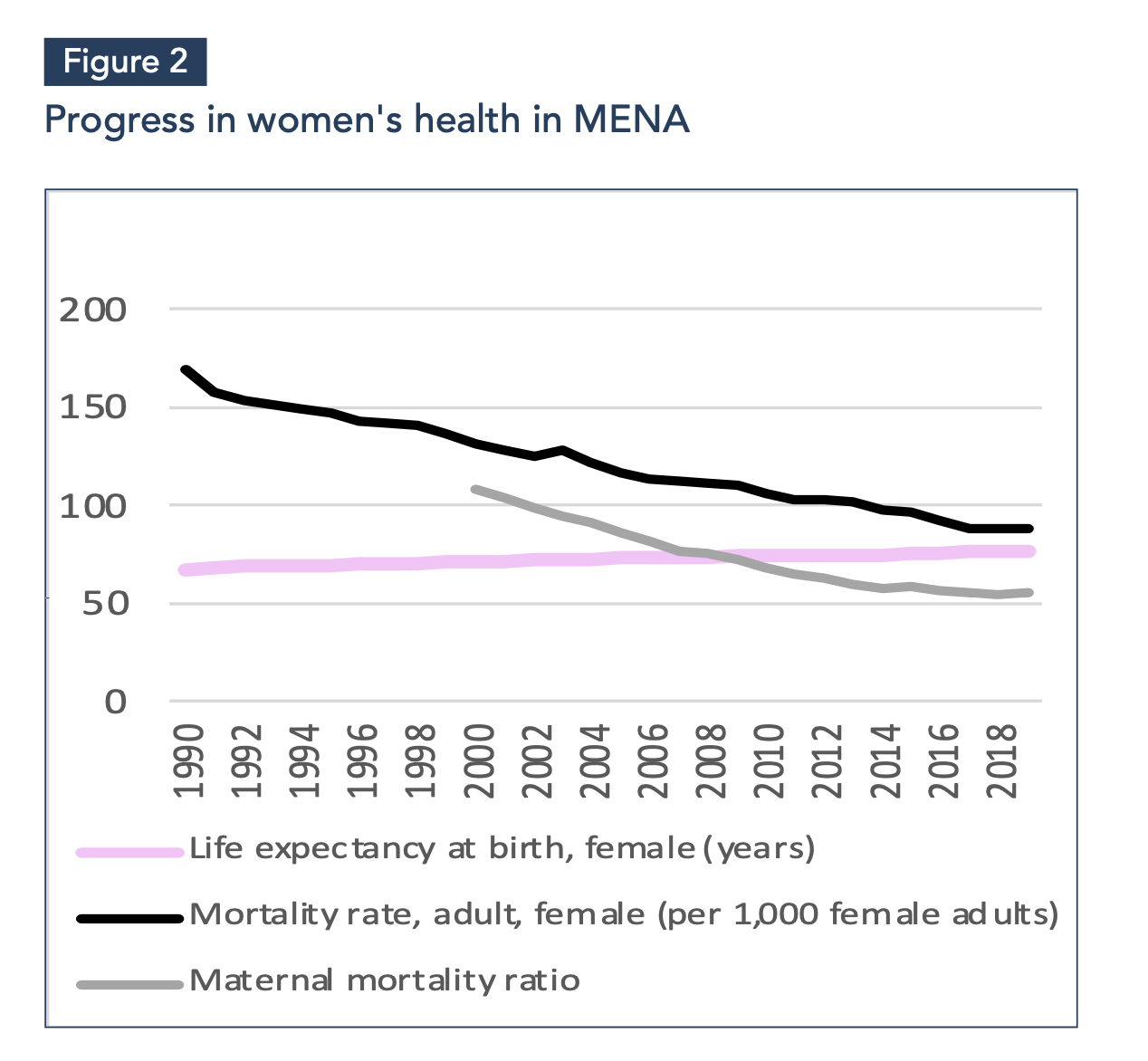

The MENA region has one of the lowest female labor-participation rates in the world, and the lowest share of women in the total labor force (Figure 1), despite significant progress in reducing gender inequality in health and education (Figure 2). This situation has contributed to the so-called “MENA gender-equality paradox” (World Bank, 2013).

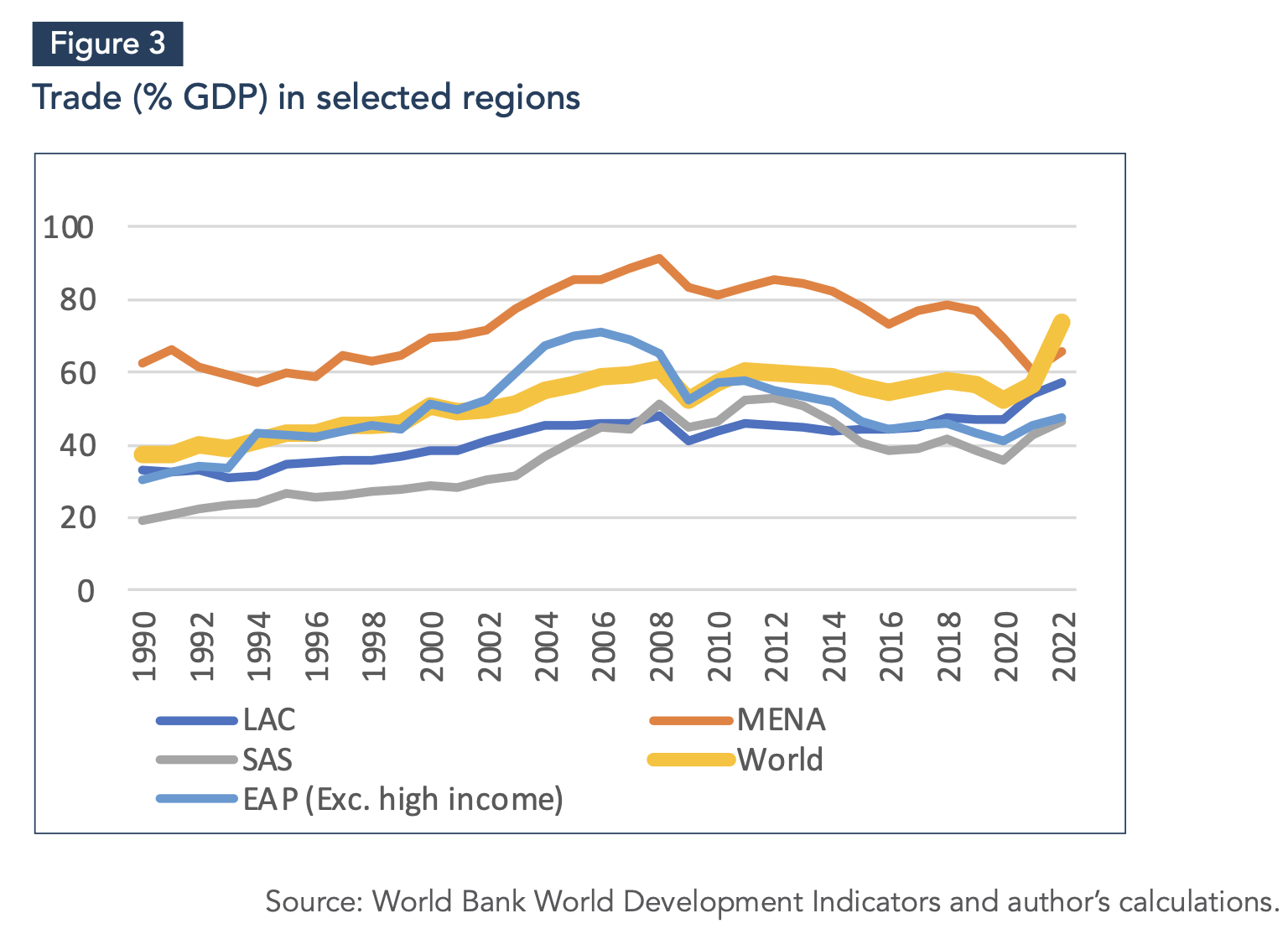

At the same time, trade openness in the region (Figures 3) is much higher than the world average and other regions, such as Latin America and East Asia and the Pacific, where female labor-force participation is substantially higher than in the MENA region. The significant trade expansion from 1990 to 2019 was mainly due to a reduction in tariffs and the signing of several regional trade agreements (RTAs) by some of MENA countries. For example, Egypt, Morocco, and Tunisia signed 19 RTAs over this period (Lopez-Acevedo and Robertson, 2023) and, consequently, experienced significant expansions in international trade.

It is important to determine whether increased trade openness has (or has not) contributed to the persistence of the ‘gender equality paradox’ in the MENA region. Even when trade is shown to benefit women in specific firms or industries, it still needs to be determined whether these gains from trade are sufficiently large and widely distributed to attract more women into the labor market and to increase women’s wage employment. Thus, a key question is: how does trade openness affect women’s participation in the labor force and wage employment at the macro level?

TRADE AND WOMEN IN THE LABOR MARKET

Integration into global trade has undoubtedly benefited many countries around the world. International trade has generally produced positive effects and has confirmed the predictions of the standard trade theory: that a country’s increased trade openness improves its national welfare. The benefits of trade for women, in particular, can be substantial. Trade can considerably improve women’s livelihoods, create new and better-paid jobs, and increase women’s bargaining power in society. However, the gains from trade are not automatic and, as research has noted, “women’s relationship with trade is complex, as it can also lead to job losses and a concentration of work in lower-skilled jobs” (World Bank and World Trade Organization, 2020).

International trade theory recognizes that the gains from trade are not distributed evenly between and within countries, and that some groups may experience losses, rather than gains, from trade liberalization. The effects of trade may depend on an individual’s skills, age, or gender, as well as the industry or firm the individual works in (export or import- competing industry). Therefore, we should expect to see different effects of trade openness on different groups in society, in which case, policymakers should implement appropriate policy measures so that adversely-affected groups do not bear most of the cost of an economy’s adjustment to greater integration into global trade.

Empirical studies show that firms that are integrated into global trade (by exporting, importing, or involvement in global value chains) have higher shares of women in their workforces, and pay higher wages relative to firms that are not integrated into global trade (World Bank and World Trade Organization, 2020). Studies, for the most part, have shown that trade expansion has had a positive impact on female employment in developing countries, but this was largely concentrated in unskilled manufacturing. However, “the bulk of the evidence suggests a widening gender wage gap as a result of freer trade” (Papyrakis et al, 2012).

Recent experiences of North African countries suggest that expanding trade has led to either lower female labor-force participation or lower wages, or both. The 2023 World Bank Middle-East and North Africa Development Report (Lopez and Robertson, 2023) found that increased exposure to exports reduced informality and female labor-force participation in Morocco and Tunisia. The report stated that estimates for Tunisia indicated that a “US$1 billion increase in export exposure leads to an average decrease of 6.8 percentage points in the female-to-male employment ratio.” In Morocco there was a shift from labor-intensive to capital-intensive industries, hence the decline in informality and in female labor-force participation. In Egypt, on the other hand, expanding exports has led to higher employment but lower real wages, with no significant effect on informality or female labor-force participation.

This is in line with the results we obtained in three studies published by the Policy Center for the New South (PCNS) in 2020-2022. We found that while trade openness increased women’s wage employment in most regions of the world, it had the opposite effect in MENA countries: increased trade openness caused a reduction in women’s share (percentage of total non-agricultural employment) of wage employment in the non-agricultural sector (Baliamoune-Lutz, 2020, 2021a). We also showed that in most developing regions, trade openness increased the share of women in the labor force after those regions had reached a certain level of trade openness (threshold effect). In MENA countries, however, the overall effect has been negative: increased openness to trade, in the first two decades of the twenty-first century, has reduced the share of women (relative to men) in the labor force in MENA countries. In contrast, for Latin America we consistently found a positive impact of trade openness on women’s share of the labor force (Baliamoune-Lutz, 2021b).

YOUNG PEOPLE IN THE LABOR MARKET: THE MENA PARADOX LIVES ON

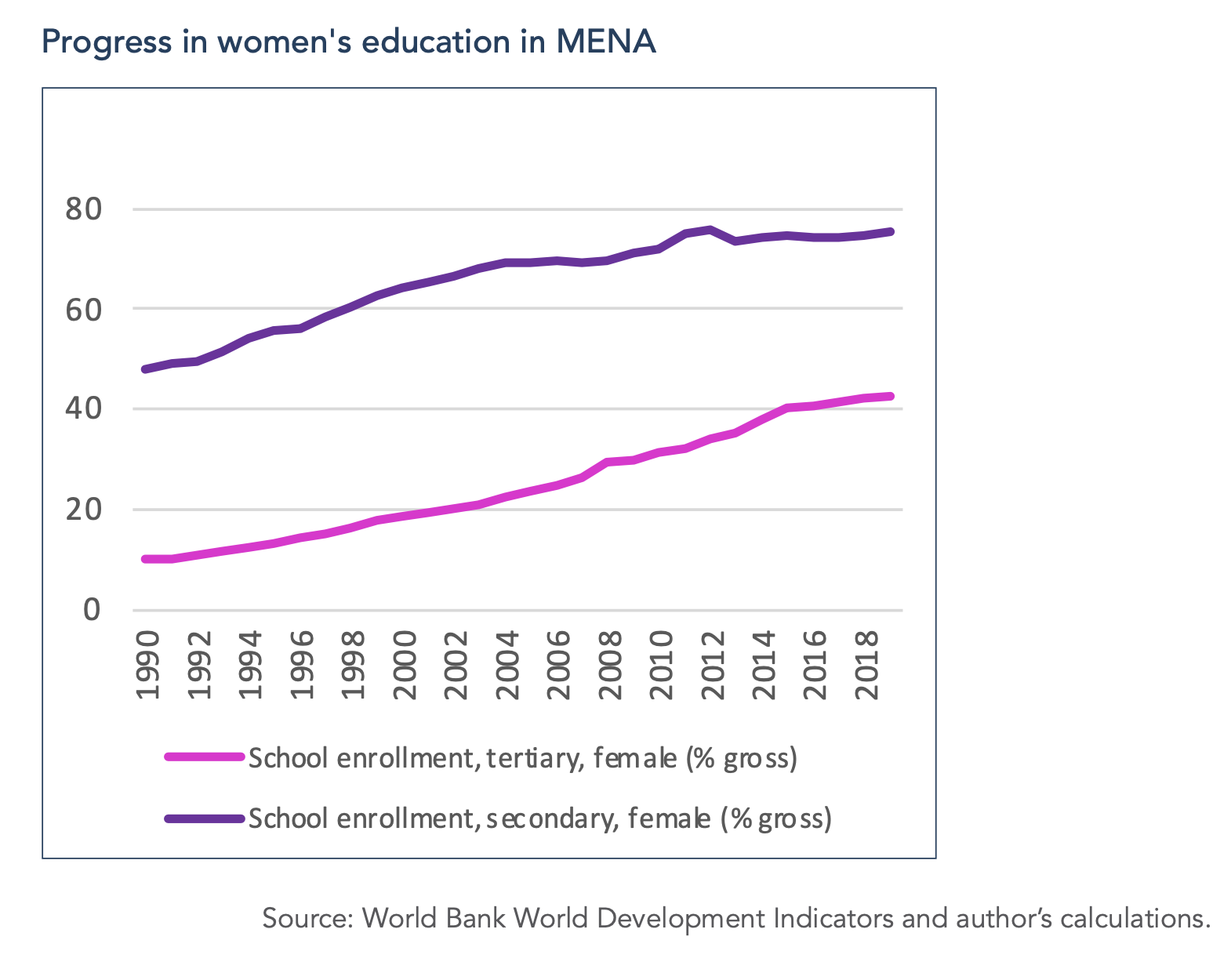

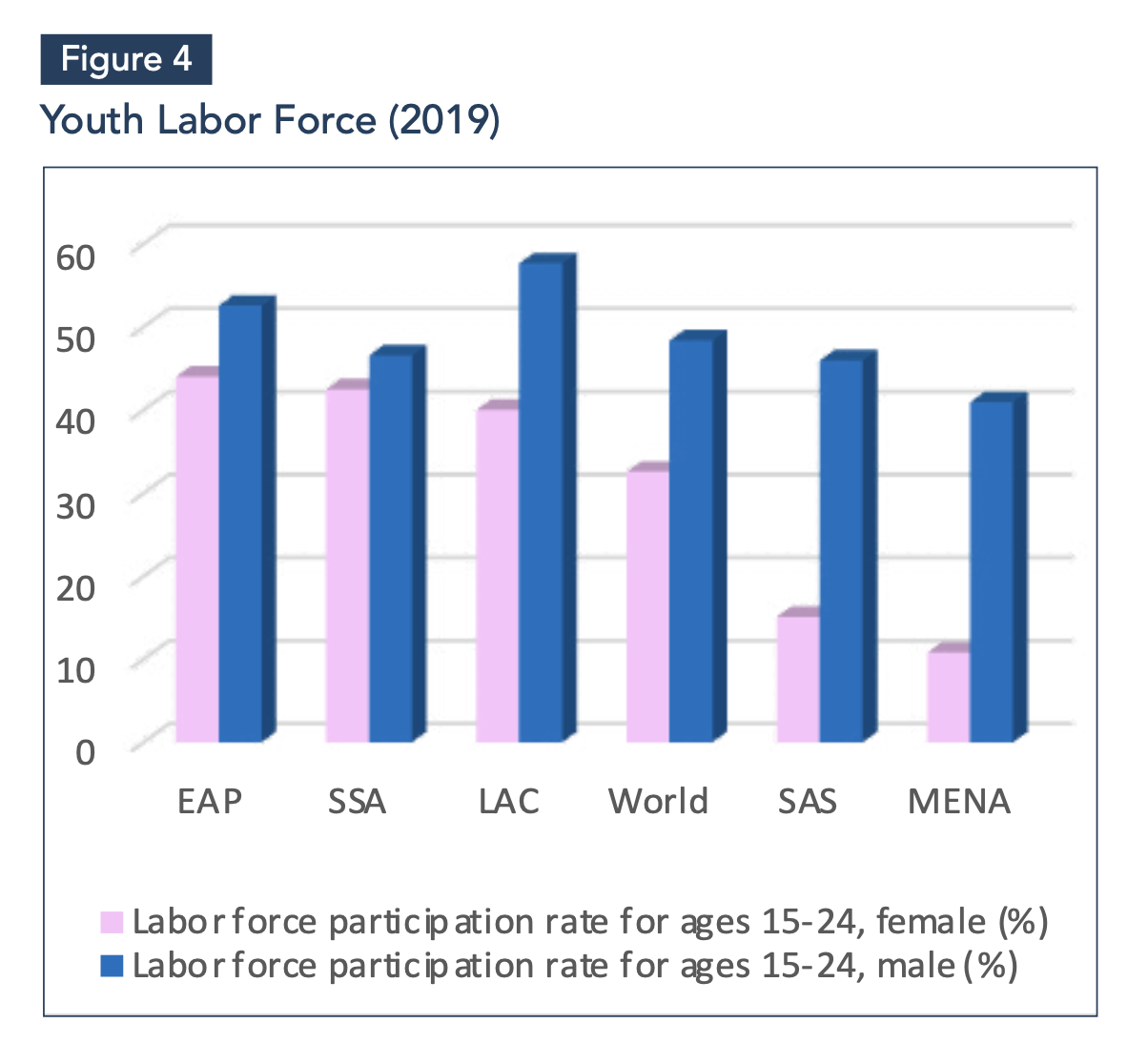

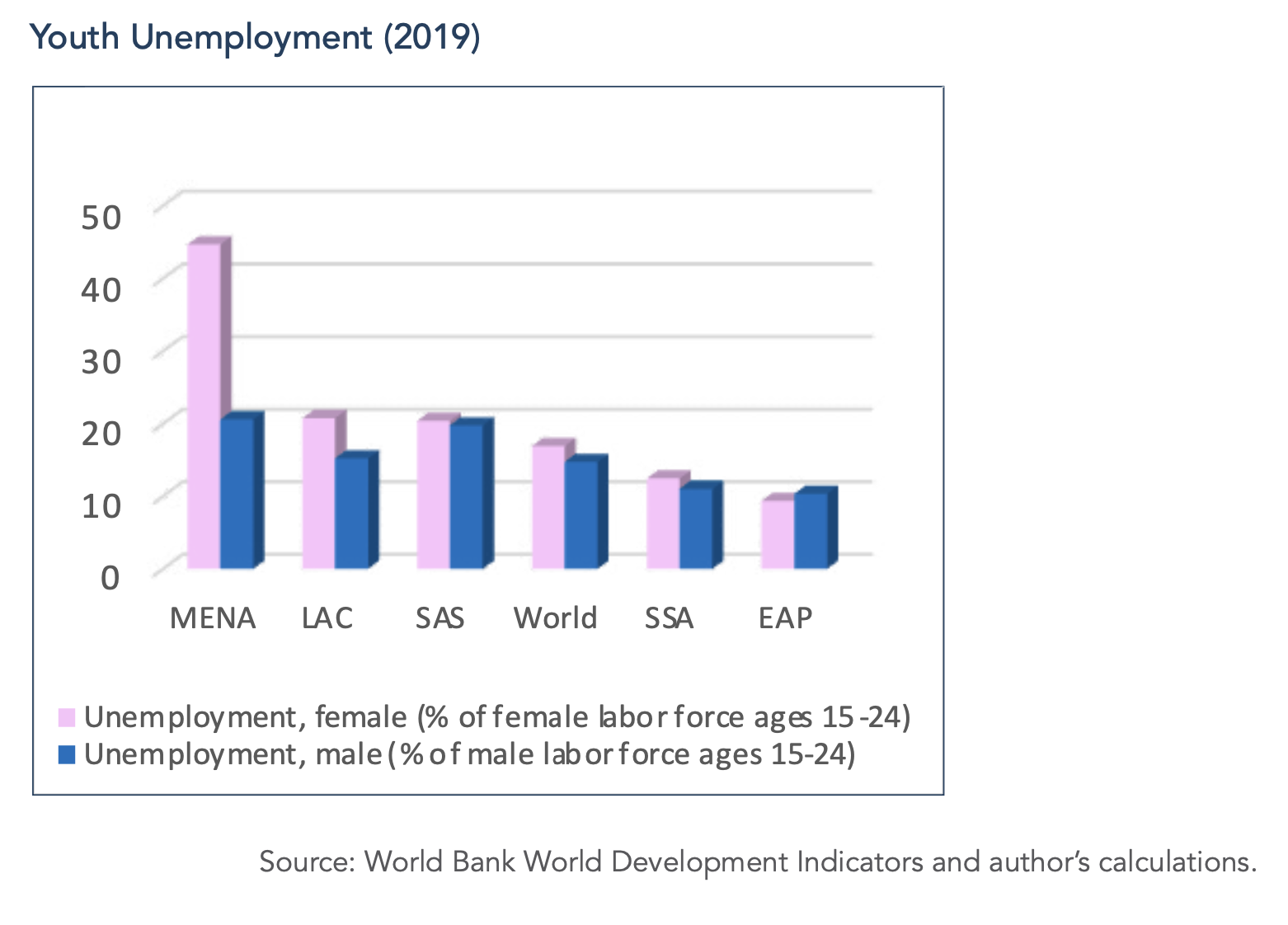

Given the significant progress in female health and education in the last three decades, it is reasonable to expect that trade would benefit younger female workers, and we should expect to see a significantly lower gender gap in the youth labor force in MENA countries, relative to the gender gap in the total labor force. Clearly, this is not the case (Figure 4). The gender gap is also reflected in the employment gap: unemployment rates for young women are significantly higher than those for young men.

HAS TRADE HELPED YOUNG PEOPLE IN THE LABOR MARKET AND MODERATED THE PARADOX?

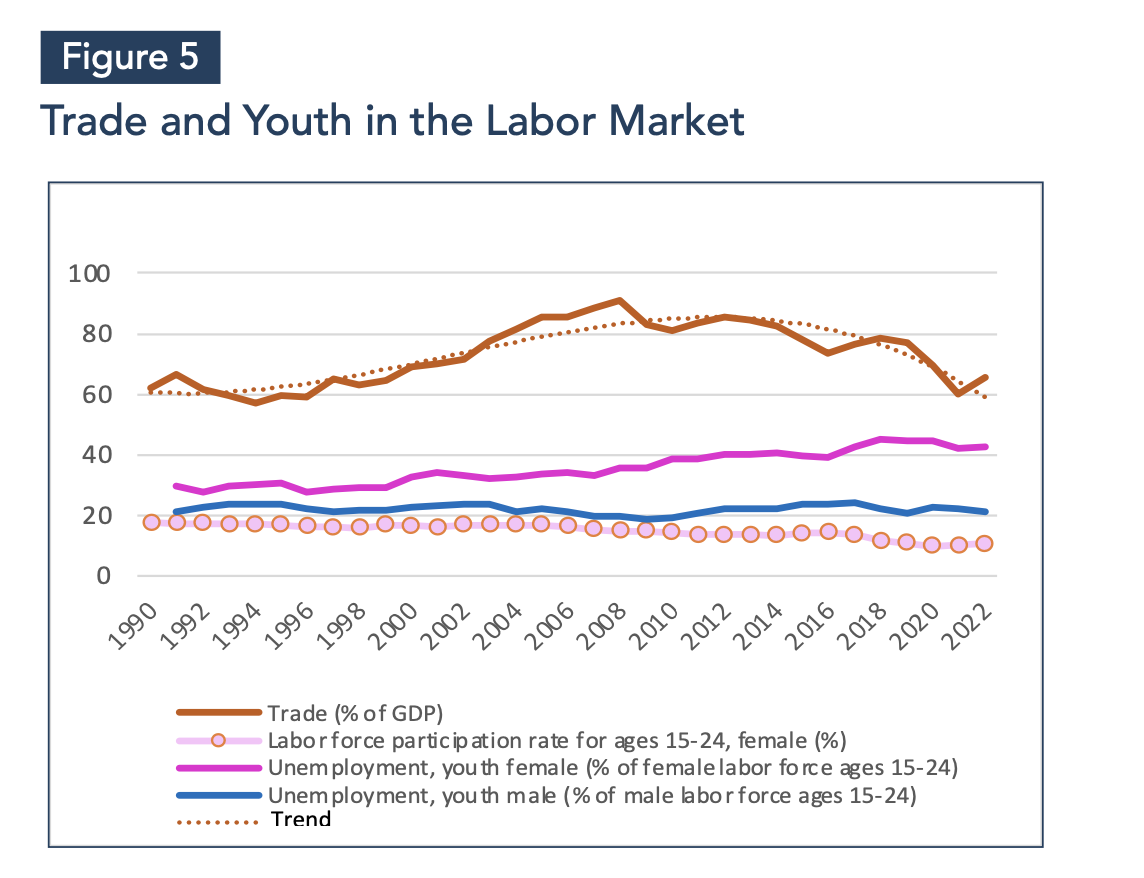

Trade has not been able to reduce youth unemployment in the region in the last three decades, despite significantly better educational outcomes and improved access to information communication technologies (ICTs). Interestingly, greater integration into global trade has exacerbated the MENA Gender Paradox. Figure 5 shows that the significant expansion in international trade that started in the late 1990s has been, in fact, associated with a substantial widening of the gender gap in employment, with female youth unemployment rates rising, and those for young males falling slightly.

Trade expansion also seems to be associated with a large decline in female youth labor- force participation, from about 15.8% in 1998 to 10.4% in 2022 (which is almost the same as the rate prevailing right before the pandemic, which was 10.8% in 2019). Figure 5 shows that the widening in the gender gap started around the same time that trade embarked on its expansionary trajectory.

This decrease in the labor-force participation rate is not mainly due to girls staying in school and out of the labor market. Data (see for example, World Bank World Development Indicators) show that MENA countries have much higher shares of young females not in employment, education, or training (NEET), relative to the shares of young males. For example, in Algeria the NEET share was 31.69% for young females and 10.94% for young males in 2017 (the latest year for which these data are available). In 2019, in Egypt, Jordan, and Lebanon, the share of young female NEETs was 40.35%, 43.78%, and 28.89%, respectively, while the male youth shares were 16.45%, 29.32%, and 17.91%, respectively.

A recent study (Baliamoune-Lutz, 2024 [forthcoming]) reports empirical findings that are consistent with the observed situation in MENA countries: greater integration in global trade reduces male unemployment but not female unemployment, thereby increasing the gender gap in unemployment, while in Latin America, for example, trade reduced both female and male youth unemployment. Similarly, research published by PCNS (Baliamoune- Lutz, 2022) confirmed this and also found evidence that trade reduces young women’s participation in the labor force.

ECONOMIC SECTORS AND THE PERSISTENCE OF THE MENA PARADOX

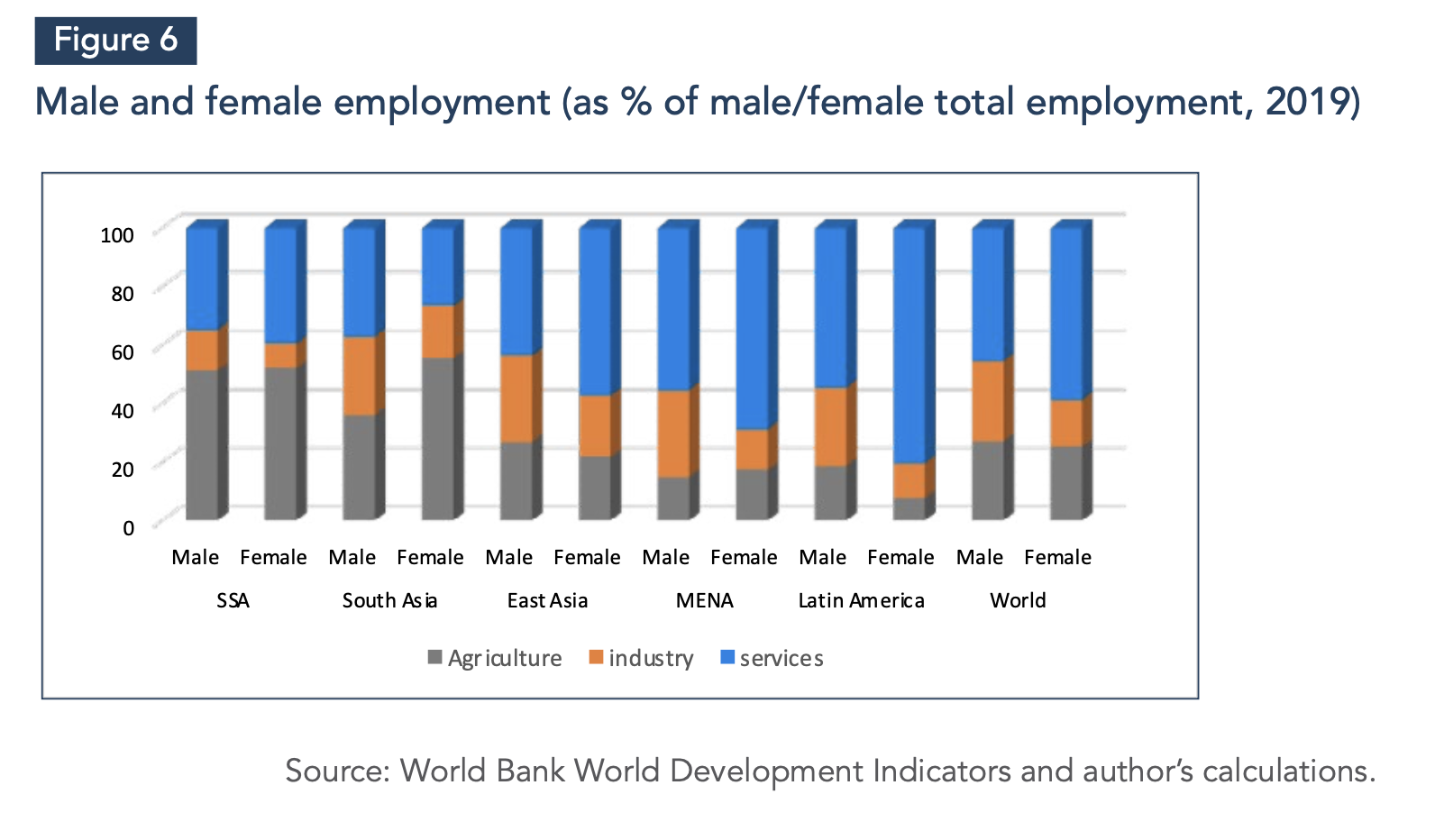

The sectoral composition of a country’s economy can also contribute to the persistence of gender inequality as the country’s trade expands. Countries with exports concentrated in capital-intensive industries do not generally experience significant positive impacts on women in the labor market, since these industries typically favor men. More than two- thirds of female employment in MENA is in services (Figure 6) and only 14% of employed women are in the industrial sector, while the share of men employed in the industrial sector is nearly 30%. Women tend to work more in less-traded sectors, and these sectors tend to face higher input tariffs (the so-called pink tariffs) compared to export sectors, limiting opportunities for wage increases and employment growth.

MENA’S PARADOX IS NOT MENO’S PARADOX1: WE KNOW WHY THE PARADOX PERSISTS AND RESOLUTE POLICY ACTIONS CAN GO A LONG WAY TOWARDS ELIMINATING IT

Many factors contribute to gender inequality in the labor market, including individual preferences, gender bias, cultural and social norms, discrimination against women in the workplace, safety issues in public spaces, and access to finance. While cultural and social norms might be difficult to influence, other factors can, and should, be addressed with determined policy and enforcement of women-friendly laws and regulations.

Policymakers should recognize that policies may not necessarily lead to the expected outcome if other factors are not taken into account. For example, Saudi Arabia has improved women’s rights in the last few years and witnessed a dramatic increase in women’s labor-force participation (from 20% in 2018 to 33% in 2020). On the other hand, Morocco, which already had greater women’s rights relative to Saudi Arabia, has further increased its recognition of women’s right in the last few years, but this has not yet been translated into increases in female labor-force participation. Further inquiry is necessary into why specific policy actions have not led to the target outcomes.

Since trade can create sectoral shifts and may lead to relocation of firms and workers, infrastructure plays an important role in improving worker mobility. Policies that target the appropriate types of infrastructure and skills can enable more mobility, especially for female workers in the MENA region. Additionally, labor-market rigidities may prevent the creation of trade-induced employment for women and young people. Policymakers should investigate the impacts of such rigidities and ease them if necessary, while mainstreaming gender in trade agreements and policy, such as by reducing or eliminating the so-called pink tariffs.

The negative impacts of trade on young women’s participation in the labor force are particularly disconcerting. They reflect chronic gender inequality in the region’s labor market and underscore the urgent need for policy actions that can deliver measurable and sustainable outcomes. The MENA paradox is not MENO’s paradox: understanding how to eliminate it is necessary and possible. We know what the problem is and why we should tackle it urgently, and we need to study further why some policies have not worked so far, and what other measures need to be put in place. Resolute polices can translate the significant increases in female health and education into a substantial rise in female labor- force participation and employment. Women in MENA countries should not have to wait 153 years to close the gender gap2.

REFERENCES

- Baliamoune-Lutz, M. (2020). Trade and Women’s Wage Employment. PCNS Research Paper no. 20/01, Rabat: Policy Center for the New South.

- (2021a). Trade and Labor Market Outcomes: Does Export Sophistication Affect Women’s Wage Employment? PCNS Policy Paper no. 15/21, Rabat: Policy Center for the New South.

- (2021b). Trade, Infrastructure, and Female Participation in Labor Markets. PCNS Research Paper no. 03/21, Rabat: Policy Center for the New South.

- (2022). Trade and Youth Labor Market Outcomes: Empirical Evidence and Policy Implications Middle East and North Africa. PCNS Policy Paper no. 02/22, Rabat: Policy Center for the New South.

- (2024) [forthcoming]. Does Trade Openness Affect Youth Unemployment? New Evidence from Developing and Emerging Economies. Economics Bulletin.

- Lopez-Acevedo, Gladys, and Raymond Robertson, eds. (2023). Exports to Improve Labor Markets in the Middle East and North Africa. Middle East and North Africa Development Report. Washington, DC: World Bank. doi:10.1596/978-1-4648-1972-8.

- Papyrakis, E., Covarriubias, A., and Verschoor, A. (2012). Gender and Trade Aspects of Labor Markets. Journal of Development Studies, 48(1): 81–98.

- World Bank. (2013). Opening Doors: Gender Equality and Development in the Middle East and North Africa. Washington DC: World Bank.

- World Bank and World Trade Organization. (2020). Women and Trade: The Role of Trade in Promoting Gender Equality. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- World Economic Forum (2023, June). “WEF Global Gender Gap Report 2023.” https:// www.weforum.org/publications/global-gender-gap-report-2023/

-------------------------------------------------------

1. I created this statement to affirm that research into how to eliminate the MENA gender equality Paradox is necessary and possible, in contrast to the idea that inquiry is either impossible or unnecessary in Meno’s argument to Socrates (and its reformulation by Socrates as a dilemma): “And how will you search for something, Socrates, if you don’t know at all what it is? What sort of thing from among those you don’t know will you make the target of your search? Or even if you were to hit upon it with complete success, how will you know that this is the thing you didn’t know?” This argument, dubbed Meno’s paradox, has often been reformulated as: “If you don’t know what you’re looking for, inquiry is impossible. If you know what you’re looking for, inquiry is unnecessary”.

2. See the World Economic Forum (2023).