Publications /

Policy Brief

- Brazil’s latest tax reform will replace five taxes on consumption with one single VAT to promote greater efficiency and sectoral isonomy.

- Forecasts produced by a detailed ICGE model point to sizeable gains in GDP exceeding 4% in the long run, even if spatially unequal.

- Exceptions to the rules reduce potential benefits in efficiency terms.

- Policies meant to promote regional development and close the gap deepened by the reform partially achieve their goal at the expense of efficiency gains.

- Lessons for the current tax reform in Morocco are drawn.

Main takeaways

- Reforming consumption taxation is an utmost priority in the Brazilian case, but further (and complementary) advancements can be made by overhauling income and property taxation, especially from a regional standpoint.

- Great effort is needed to battle private interests and detrimental lobbies that seek to claim exemptions from the headline VAT rate. This includes inhibiting further changes to the already extensive list of sectors receiving preferential treatment.

- Compensatory regional government spending in poorer states does not seem to be efficient from a macroeconomic perspective and could be revamped if income transfer schemes are to produce gains in comparison to richer states.

1- Introduction

The comprehensive tax reform enacted by the Brazilian Congress at the end of 2023 is the first step towards meaningful modernization of the country’s tax system and introduces a series of innovations aligned with international best practices.

Set to be replaced are the current five taxes on consumption that had been gradually created since the introduction of the current Constitution and that in 2019 raised BRL 918 billion, or 12.43% of the GDP, in revenue. Each with a different tax base and specific rules, these five duties have hampered economic activity through three main phenomena. First, inefficient allocational incentives caused by arbitrary differences in effective rates for different products and regions. Second, loss of competitiveness in global trade due to residual taxation embedded in exports. Third, increased costs to comply with extensive paperwork requirements.

An effort dating back to the 1990s, the actual promulgation of a tax reform is a major political achievement considering the variety of private interests linked to tax matters. Consumption taxation is particularly relevant due to Brazil’s above-average reliance on it. While OECD countries get on average 34% of their total tax receipts from taxes on goods and services, the percentage for Brazil reached 45% in 2019. Although positive at first glance, changes to rules so influential for production decisions have the potential to cause unforeseen effects due to their second-order nature, as they occur only as a delayed response to initial shocks. These necessitate special treatment in terms of forecasting for its potential to anticipate policy needs.

At NEREUS, the Regional and Urban Economics Lab at the University of São Paulo, we developed two technical reports to study the long-run effects of the tax reform. The first one was published in August 2023 and focuses on the process of replacing old taxes with a new VAT, while the second, published in October 2023, concentrates on the National Fund for Regional Development. This policy brief is a summary of the reform and our main findings.

2. Reform basics

The five old taxes on consumption will be substituted for two quasi-identical twin VATs named IBS (federal government) and CBS (states and cities). They share the exact same rules, differing only on the destination of their proceedings. The tax base, final consumption, is also the same for both. This constitutes a significant departure from the selective and cumulative nature of the old taxes when each had a specific tax base (e.g., manufactured goods vs. services) and oftentimes would integrate the tax base of one another. These features try to tackle the last two aforementioned phenomena. Exports are truly exempt as taxes paid on inputs can be reimbursed, and harmonized tax codes eliminate the regional and sectoral compliance efforts necessary under the previous system.

A final feature of the tax reform tackles the first phenomenon. The headline rate will be applicable to all consumption (with a small but substantial list of exceptions) and will be collected where it occurs, not where the good or service was sourced from. The idea is to end spatial or sectoral differentiation, eliminating distortions caused by years of lobbying. This is especially relevant as goods deemed to be non-tradable enjoy a lower effective rate on average than tradables (4.7% vs. 10.8% of the gross output in 2019), and tax breaks are a pervasive tool for regional development in Brazil.

3. Adjustments

Although the ideal reform would closely follow the principles described above, the political process meant some adjustments had to be made to appeal to lawmakers worried about losses in their respective constituencies. Perhaps the most controversial modification was the extensive list of sectors favored with a 60% lower rate, going against the ideal of isonomy. Other amendments include a federal fund to honor previously granted tax breaks until 2033 and the maintenance of special tax status for goods produced within the Manaus free trade zone.

4. The headline rate

The tax reform explicitly determines that the VAT headline rate must be calculated to conserve the average tax revenue generated by the five replaced taxes in the 2012-2021 period as a proportion of the GDP. Thus, a simple division yields the necessary rate to fulfill these demands when considering the sectors exempted. The combined rate would be 29.88% – 18.77% for regional governments through the IBS and 11.11% for the federal government through the CBS. If implemented, this VAT would be the highest in the world, almost three percentage points above Hungary, today’s highest rate.

However, the potential of the reform to increase GDP, and consumption even more, means we need to consider the tax base growth relative to GDP growth to obtain the correct rate. Using the forecasts explained in the following section, the final rate would be 25.61% (16.09% for IBS and 9.52% for CBS).

5. Forecasted effects

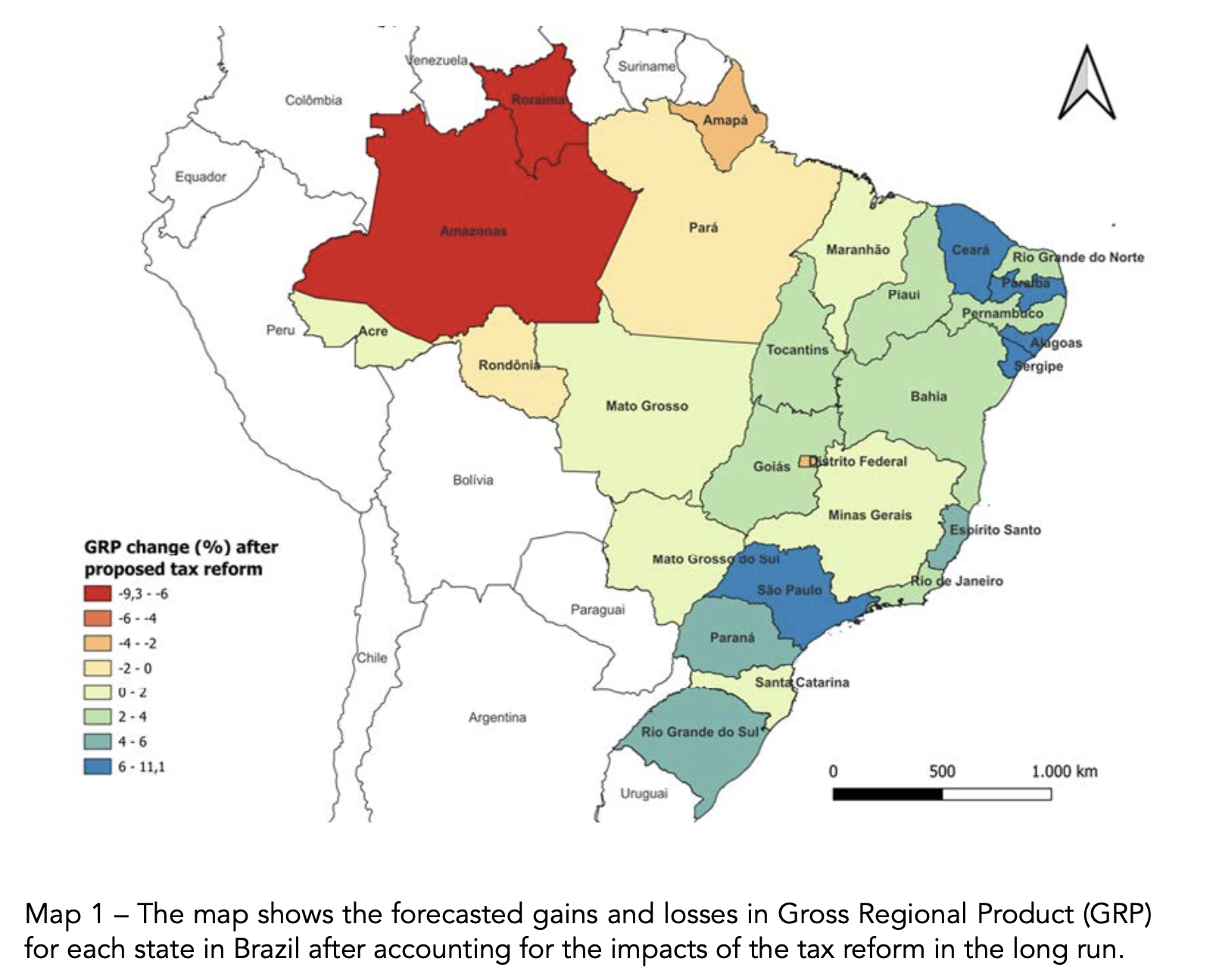

Using a detailed Interregional Computable General Equilibrium (ICGE) model of Brazil calibrated with 2019 data we simulated how the Brazilian economy would react to the new rules in the long run. The methodology supplies us with insights on trajectories and spatial distributions of production and employment. Findings corroborate some of the optimistic claims about the reform: GDP shows to be around 4.5% higher than the benchmark in the long run, with 3.6% attributable to gains derived from factor reallocation and 0.9% from other sources of productivity gains. However, regional distribution of these gains is far from balanced (see Map 1).

In fact, rich states tend to benefit greatly from the reform, with only a subset of the poorer regions to see gains. The historically disadvantaged but populated states of the Northeast all witness sizeable increases to their GRP, while the less populated but equally poor states of the North all suffer decreases. A detailed look at the macroeconomic aggregates for each state reveal that migration occurs out of the Northern states and into some of the states of the Northeast and Southern regions. This partly explains the losses found, but another condition plays an important role in determining the GRP outcomes. The shift from origin to destination when collecting taxes significantly decreases revenue for states that concentrate production. Amazonas, for example, hosts the Manaus free trade zone, a manufacturing hub with nationwide relevance. Bahia and Pernambuco are also important regional players. It is possible to note that these states have a poorer performance than comparable peers, which could be attributable to losses stemming from decreased tax revenue and thus governmental spending.

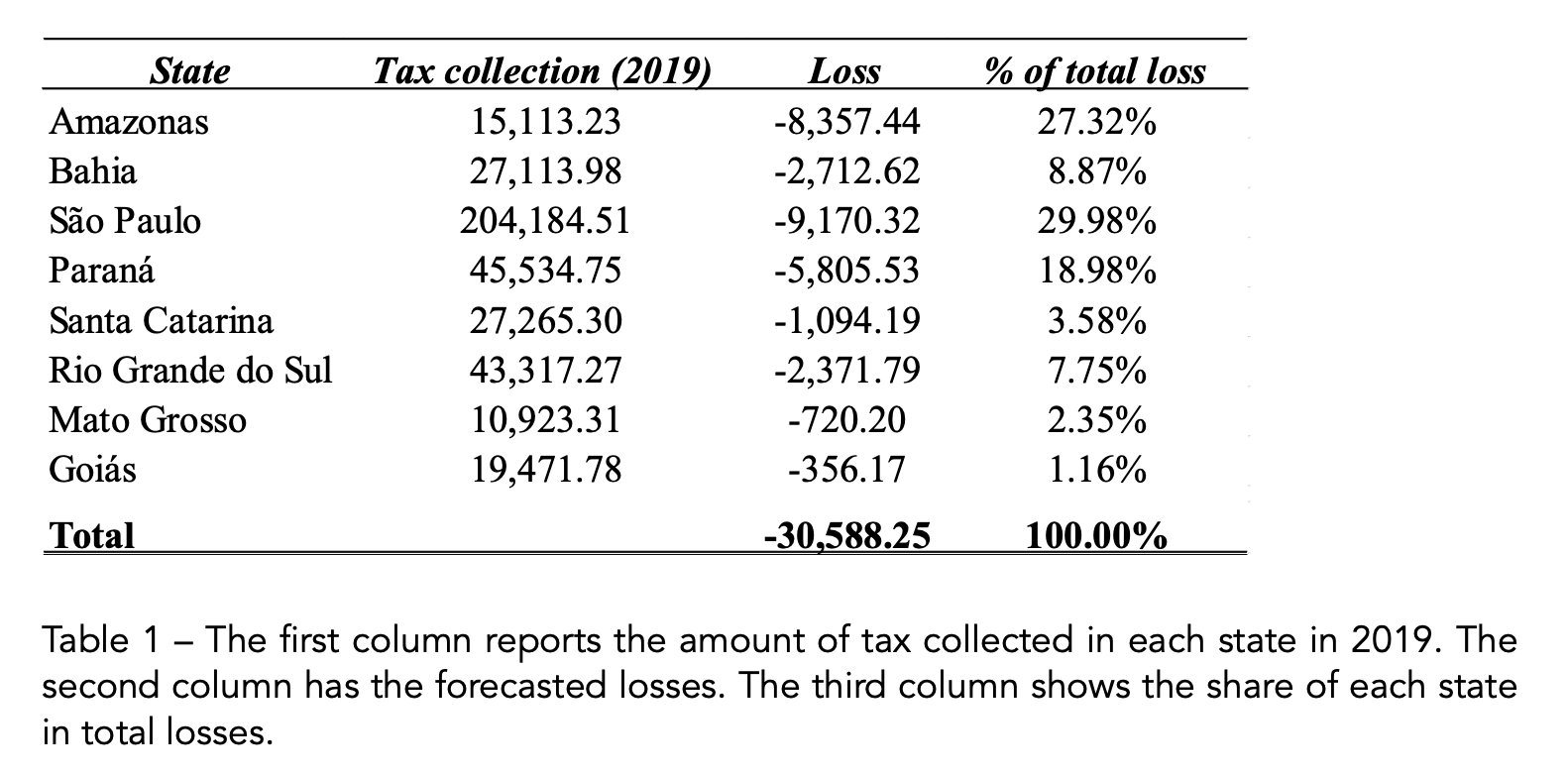

To quell protests stemming from representatives of these states, the federal government has guaranteed that tax receipts for states and municipalities will not fall below the average recorded between 2022-26. Thus, we create an alternative scenario where states that are forecasted to witness losses in their tax collection (Table 1) are compensated to sustain their 2019 revenue. The effects, nonetheless, go against what would be expected from such an initiative. While Amazonas goes from a net loss to a net gain in GDP, almost all other losing states deepen their costs, with a small number of winning states expanding their gains. Other states just have their impacts attenuated.

6. Dealing with regional inequality

Anticipating unequal effects across states, representatives lobbied for the inclusion of an income transfer scheme meant to promote regional development and reduce spatial inequality. The National Fund for Regional Development (FNDR) will have resources injected yearly by the federal government and distribute 0.6% of the GDP (2022 proportion) to states according to population and income per-capita measures. The latter is aligned with the overall goal of reducing inequality by adopting a distributional pattern that favors relatively poorer states on a per-capita basis and will account for 70% of the fund’s money. The former is responsible for the other 30% and uses population weights, a request from richer and more populous states that would receive close to nothing under the first allocation rule.

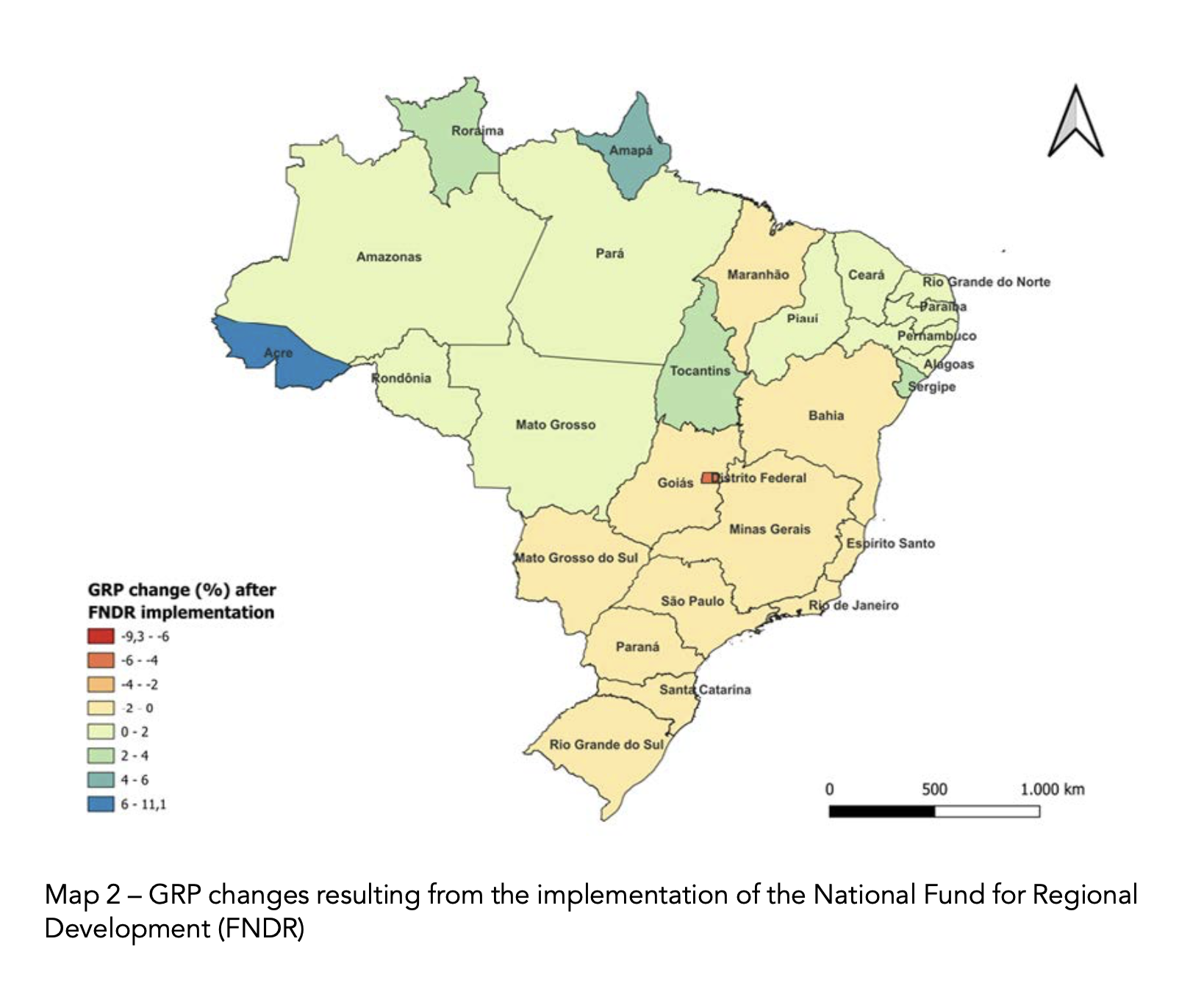

When incorporated into our model, the FNDR achieved its goal of spurring growth in poorer states as seen in Map 2. Compared with the effects of the tax reform we can note significant complementarity. While the previous changes were detrimental to the Northern and some Northeastern states, the FNDR is primarily positive for these same areas. Nevertheless, the aggregate results paint a concerning picture – although isolated regional effects can be positive, nationwide GDP would decrease by about 0.21%. The gains from a tax reform would more than cover these losses but still showcase a clear trade-off between efficiency and equity.

States in the Amazon area pushed even further and successfully claimed the creation of another fund maintained by the federal government to further finance development programs in their territories. Details about this new scheme are all set to be defined in a later bill, so no precise forecast could be made for its effects.

7. Conclusion

The tax reform is a significant step forward in modernizing the Brazilian tax framework and has the potential to unlock sizeable gains just by harmonizing rates and rules. Although watered down by the inclusion of exceptions and coming short of eliminating all special treatments, the reform aligns Brazil with the global taxation status quo. Our forecasted gains in GDP, however, are not as big as other studies have achieved, and their spatial distribution is significantly unequal. Policies to deal with these unwanted consequences are thus warranted, but current proposals all merit further refinement as they adversely impact the efficiency gains promoted by the tax reform.

While the external validity of the results for Brazil requires caution, given other economies’ differences in their economic structures, their levels of development, and their institutional frameworks, there may be common trends that could be of importance to shed light into specific issues. In the case of Morocco, the current tax reform, despite being less extensive than the Brazilian one, will also generate important changes in relative prices by reducing the range of VAT rates partially eliminating some of the existing distortions across sectors. The 2024 VAT reform in Morocco is centered around four main points: (i) extension of VAT exemption to encompass almost all essential consumer goods (of extensive consumption); (ii) shift towards two consolidated rates – the current four rates of 7%, 10%, 14%, and 20% will converge, by 2026, towards rates of 10% and 20% exclusively; (iii) expansion of the VAT’s tax base, particularly through the imposition of VAT on remote digital service provisions; and (iv) establishment of a novel withholding tax system as a means of streamlining VAT collection. Essentially, the tax reform will change the rules by which VAT collection is determined.

According to the Ministry of Finance, the anticipated fiscal impact of the proposed reform would generate additional VAT revenue of around 1 billion MAD by 2026. It will be important to understand how economic agents will adapt to the new set of rules. These aforementioned, first-order (direct), fiscal impacts are important, no doubt, but can only reveal a fraction of the long-run impacts of the reform. Second-order effects impact the size of the tax base because of shifting incentives that alter the allocation of capital, labor, consumption, and investments across sectors and regions. It is particularly important to estimate second-order effects to assess the true ramifications of a tax reform since many if not all the potential benefits of a reform affect the economy through improvements to efficiency. Reducing artificial barriers and incentives that influence allocation and hamper compliance can spur growth, which in turn increases tax receipts by expanding the tax base. Given that the Moroccan economy is not homogenous internally, remarkable differences across sectors, income groups, and regions may emerge from the current reform.

Finally, concerning the implementation of a tax reform, as witnessed in Brazil, given unwanted distributional consequences, potential losses are a hard political pillow to swallow. Stakeholders, which may now have an over-sized influence on the reform’s terms, are careful not to weaken their power and potential gains. The political resistance is not unforeseen; in fact, one could argue most attempts at enacting changes fall short of being approved because they cannot appease the multitude of interests deeply concerned with changes to tax rules everywhere.