Publications /

Policy Brief

Pan-Atlantic cooperation is inspired by the opportunity to foster rising, widespread, and sustainable prosperity across Atlantic Basin societies, particularly in Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC). The key to unlocking this potential lies in deepening the Atlantic Basin’s already high level of intra-regional economic interdependence (when viewed as a single regional entity) and leveraging the untapped complementary opportunities within and across the Southern Atlantic. Furthermore, currently unfolding dynamics of economic and strategic decoupling also point to the potential for pan-Atlantic cooperation to channel some of the ‘x-shoring’ (i.e., ‘reshoring’, ‘friendshoring’ and ‘nearshoring’) of Northern Atlantic Plus supply chains into the Southern Atlantic.

Recap

In Policy Brief 5[1] in this series (Pan-Atlanticism: The Atlantic Basin in a Multipolar-Transnational World), we explored the conceptual comparison of realism and liberalism with respect to the evolution of the international power structure and their respective perspectives on the widespread contemporary phenomenon of asymmetric interdependencies.

A central thesis of Policy Brief 6[2] was that this evolving structure of international power—from the erosion of unipolarity to the emergence of multilayered multipolarity -- is giving rise to various material and ideological factors that are steering global dynamics toward a new ‘regionalization of globalization’. Such developments could push liberals to pursue economic regionalism in innovative ways. Global economic fragmentation, triggered partly by the failures of the liberal international order, may lead liberals—along with realists—to reconsider regionalism as a strategic alternative to attempting to restore the fraying global jurisdictions of the Bretton Woods institutions. The Atlantic Basin could serve as a second-best option.

Roadmap

In this Policy Brief, we argue that both realism and liberalism within the Atlantic Basin could pragmatically converge to support pan-Atlantic cooperation and Atlantic Basin regionalism as a second-best strategy for pursuing a range of diverse yet interlocking strategic objectives among Atlantic Basin actors. This is revealed by an exploration of some of the economic drivers of pan-Atlanticism, including the existing levels of intra-Atlantic Basin trade and the growing potential for the rearticulation of global supply chains into the Atlantic Basin through the process of Northern Atlantic nearshoring into the Southern Atlantic.

Liberalism and Pan-Atlanticism (III): Liberalism and Pan-Atlantic Regionalism

Potential Liberal Drivers of Pan-Atlantic Cooperation

In our previous Policy Briefs in this series, we identified at least two potential drivers of pan-Atlantic cooperation that align with liberal perspectives:

- The Atlantic Ocean as a driver: This highlights the diverse maritime and marine challenges and opportunities inherent to the Atlantic Ocean.[3]

- The regionalization of globalization as a driver: This refers to the foreign policy-driven reconfiguration of global economic supply chains into collaborative economic frameworks, a defining characteristic of the shifting multipolar world order.[4]

Both these drivers will be explored in greater depth in this and subsequent Policy Briefs in the series. It is worth noting that the pan-Atlantic point of policy convergence between ‘pragmatic liberals’ and ‘flexible realists’—identified in Policy Briefs 5 and 6 of this series—is most likely to emerge under the least confrontational of ‘Kortunov’s scenarios’ (as analyzed in those briefs). Specifically:

- Scenario 2: A negotiated ‘reform of global governance’ structures.

- Scenario 3: A ‘revolution in global governance’, particularly the scenario’s second possible outcome—the ‘regionalization of globalization’.

This latter development in the evolution of emerging multipolarity could pave the way for more meaningful pan-Atlantic cooperation if driven by a new strategic impetus.[5]

Other liberal drivers—such as human rights and Western values—might gain traction under the more confrontational of ‘Kortunov’s scenarios’:

- Scenario 1: The restoration of unipolar hegemony.

- Scenario 3: A ‘revolution in global governance’, but in its first possible outcome: the formation of a ‘lopsided bipolarity’ where the Northern Atlantic Plus confronts the BRICS Plus.

However, these confrontational scenarios carry the highest costs for all parties involved. If war can be avoided, liberal values could still serve as a pan-Atlantic driver, fostering a new form of Atlantic Basin economic regionalism. This regionalism would align with the realist imperative to bridge the North-South divide in the Atlantic and mitigate the risk of a ‘lopsided bipolarity’ that could isolate the Northern Atlantic. Many have argued, particularly during the unipolar moment, that the Atlantic Basin region shares—albeit unevenly and imperfectly—many of the Western values underpinning the liberal international order, such as markets, the rule of law, democratic political culture, and basic human and political rights. Consequently, it has been claimed that shared ‘Atlantic values’ could serve as the primary foundation and a potential central driver for pan-Atlantic cooperation.

Many liberals in the Northern Atlantic perceive these values to also largely characterize the Southern Atlantic, and many (though not all) in the Southern Atlantic have, at various times, embraced them.[6] However, the global shocks of the past decade have undermined the perceived universality of Northern Atlantic values[7] across the world, casting doubt on the idea that common Western values could effectively serve as the foundation or initial driver for pan-Atlantic cooperation.

As Daniel S. Hamilton observed as early as 2014:

“What had been a sense of global convergence around such Western norms as rule-based institutions of collaboration, open non-discriminatory trading rules, the “democratic peace,” and the “Washington consensus” on development, has given way to a broader and more complex global competition of ideas over such issues as multilateralism, the use of force, the rights and responsibilities of state sovereignty, international justice, and alternative models for domestic governance, particularly the relationship between state and market”.[8] Indeed, while not insuperable, the persistent North-South divide across the Atlantic Basin remains a significant barrier to overcome. However, pan-Atlantic economic cooperation offers the most viable pathway to bridging this divide. A carefully designed, internationally collaborative ‘pragmatic liberal’ approach could promote sustainable development and foster shared prosperity across the Southern Atlantic.

Intra-Atlantic Trade as a Potential Driver of Pan-Atlantic Cooperation

Beyond environmental, geopolitical, and ideological drivers, the potential for pan-Atlantic economic cooperation offers another compelling driver, particularly in a scenario of continued partial global economic fragmentation.

As with global multilateralism under the liberal international order, pan-Atlantic cooperation is inspired by the opportunity to foster rising, widespread, and sustainable prosperity across Atlantic Basin societies, particularly in Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC). The key to unlocking this potential lies in deepening the Atlantic Basin’s already high level of intra-regional economic interdependence (when viewed as a single entity) and leveraging the untapped complementary opportunities within and across the Southern Atlantic.

Merchandise trade data highlights the robust intra-Atlantic trade connections:[9]

- Europe: 75% of its global (extra-Europe) merchandise trade occurs within the Atlantic Basin.

- North America: 65% of its trade is concentrated within the Atlantic Basin.

- Central and South America (excluding Mexico): Similarly, 65% of their trade takes place within the Basin.

- Africa: 55% of its trade is within the Basin.[10]

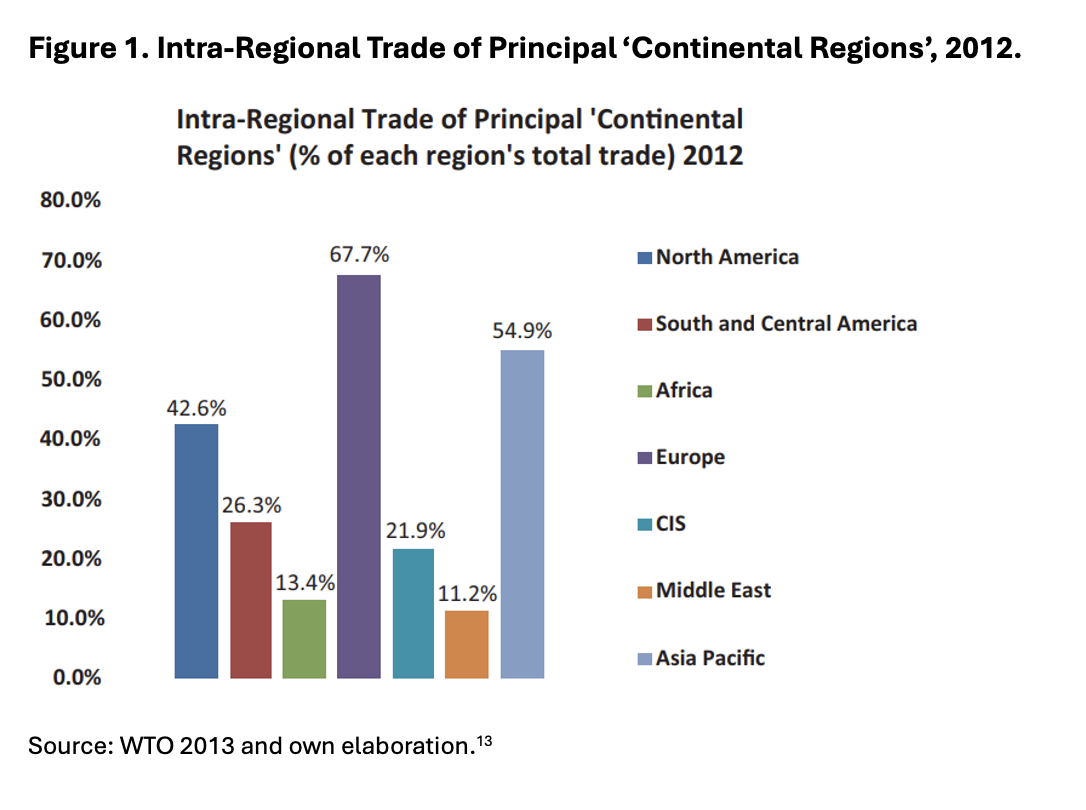

In aggregate, the Atlantic Basin region[11] is already more intra-regionally interdependent in trade terms[12] than any of its constituent continental or subcontinental regions, including Europe, which is itself highly interdependent. In other words, the Atlantic Basin is a more densely interconnected trade region internally than any of the four Atlantic continents on their own (see Figures 1 and 2).

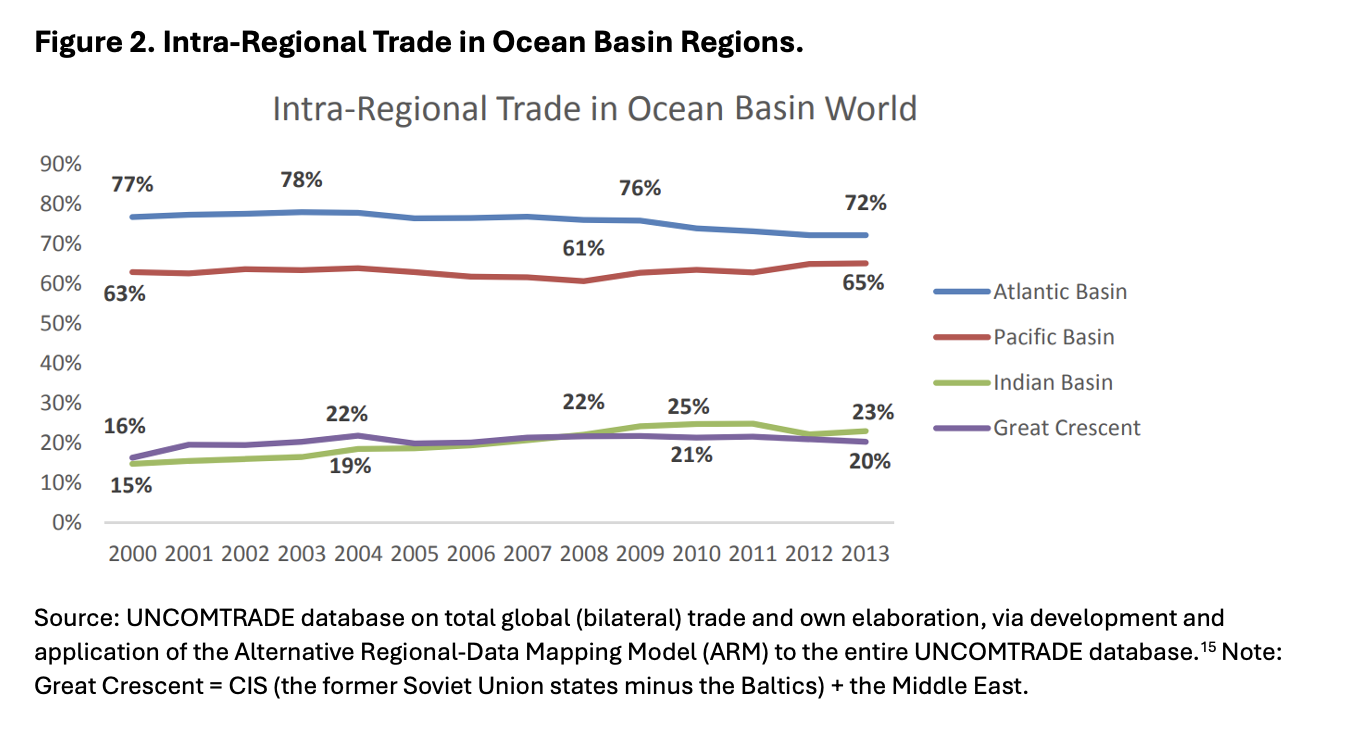

The Atlantic Basin also exhibits greater intra-dependence in trade than other ocean basins, although the Pacific Basin is not far behind. This suggests the potential emergence of new ocean basin regions (discussed further below).

In research conducted for the European Commission’s Atlantic Future project in 2015, this author noted:

“Both the Atlantic Basin and Pacific Basin exhibit very high shares of intra-basin trade—72% and 65%, respectively. These intra-regional trade shares remain more than twice as high as the corresponding shares for the entire Western Hemisphere and the world’s other ‘continental’ landmasses. The recent evolution has been relatively flat for both, with the expected slight decline in the Atlantic, and the expected slight rise in the Pacific Basin”[14] (see Figure 2).

Nevertheless, it is only by examining FDI links within the Atlantic Basin that the overwhelmingly dense and dominant nature of intra-Atlantic Basin economic connections becomes evident.

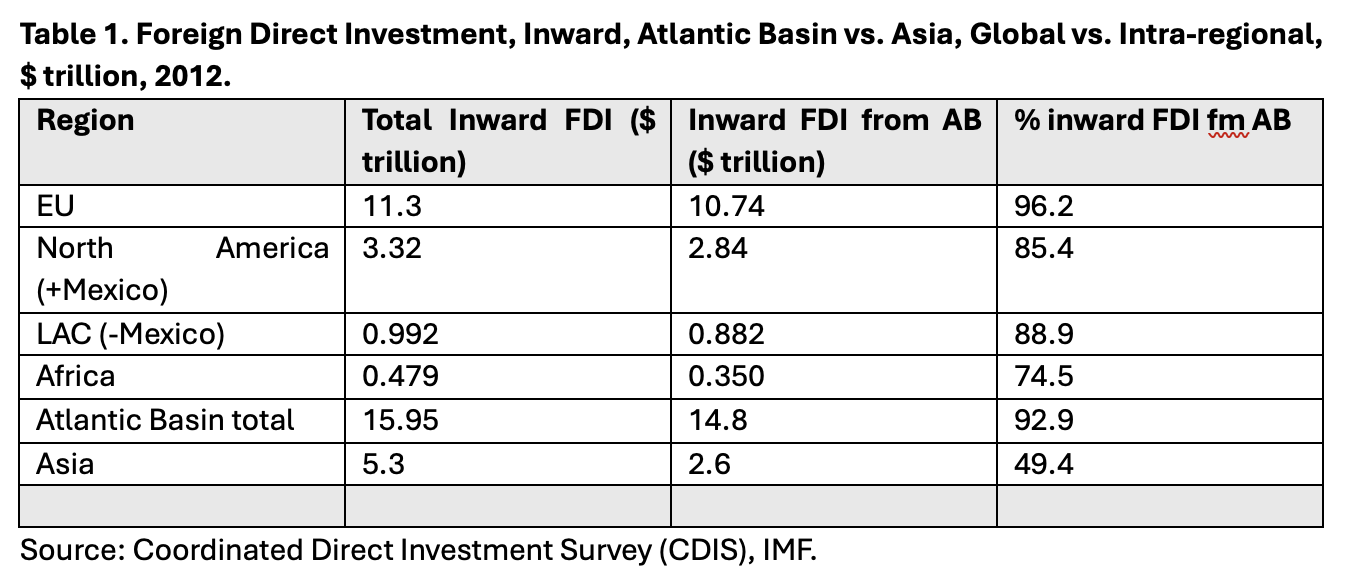

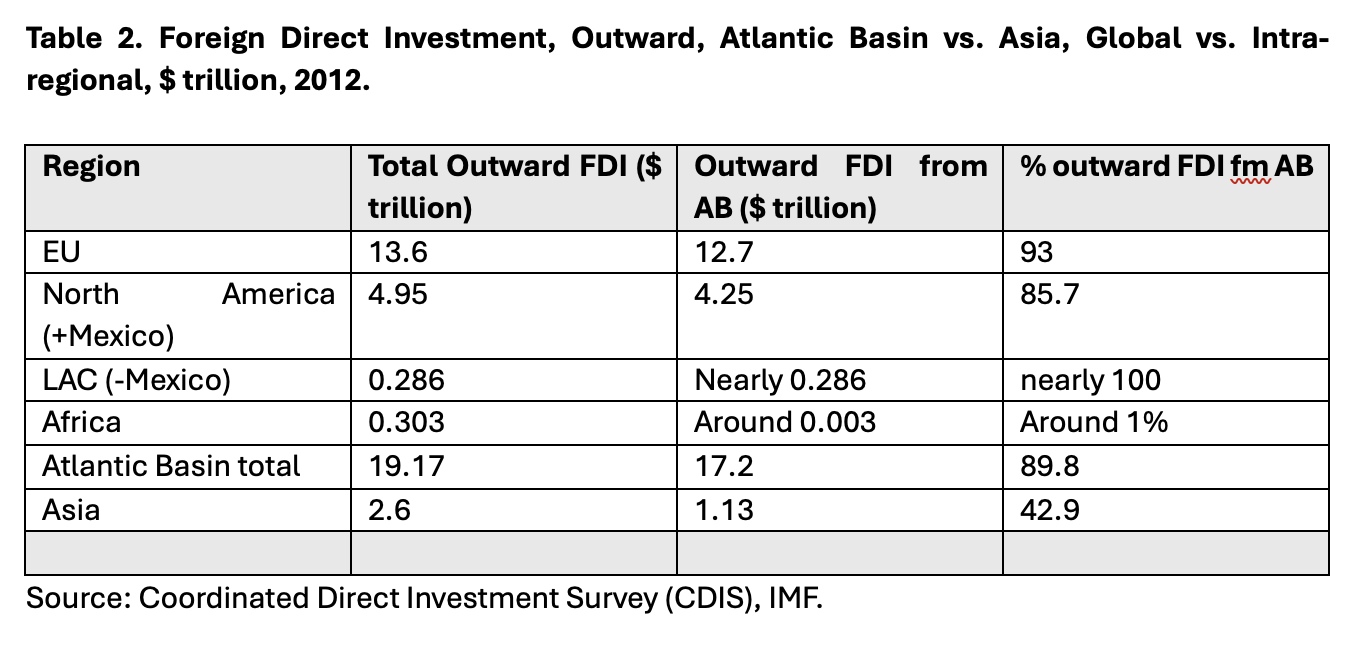

Nearly 93% of all inward FDI in the Atlantic Basin originates from within the region itself, meaning it comes from another Atlantic Basin country (see Table 1). In contrast, intra-Asian FDI accounts for only 49.4% of its total. Similarly, with respect to outward FDI, intra-Atlantic Basin flows constitute nearly 90% of the region’s total, compared to just 42.9% for intra-Asian outward FDI (see Table 2). When considering both inward and outward FDI, over 91% of all FDI flows involving Atlantic Basin countries are intra-regional, when the region is defined as the broad Atlantic Basin.

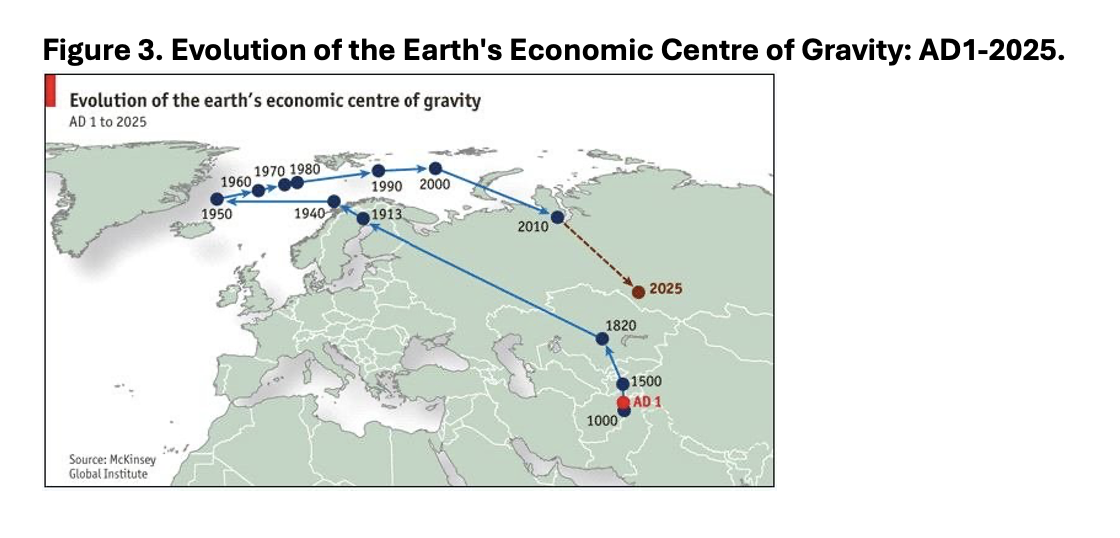

The slight decline in the ratio of the Atlantic Basin’s intra-regional trade since 2008, as shown in Figure 2, was an anticipated consequence of the evolving dynamics of globalization. Over recent decades, the global economic center of gravity has shifted eastwards with the rise of multipolarity. This eastward shift has drawn Southern Atlantic economies into an emerging, though still nascent, integration with China and the broader Eurasian region. This development, partly aligned with China’s Belt and Road Initiative, has fostered growing economic linkages across the BRICS sphere—albeit from a relatively low base compared to the Northern Atlantic.

This eastward shift in economic gravity has restructured the economic interdependencies and supply chains of the Southern Atlantic, gradually drawing them away from the Northern Atlantic into a partial alignment with Eurasia. This trend toward increasing ‘extra-regional trade’ with Asia—largely driven by exports of natural resources from Africa and Latin America and the return flows of Asian/Chinese manufactured goods, investments, finance and loans to the Southern Atlantic—accounts for the modest decline in intra-Atlantic Basin trade, from 77% to 72%, since 2000 (see Figure 2).

Despite this erosion, the level of intra-Atlantic interdependencies remains remarkably high: over 70% of all international trade (and 90% of all FDI) by Atlantic Basin countries still occurs within the basin. This fact presents a compelling prima facie argument that the Atlantic Basin has the potential to function as a viable and successful economic region. As noted:

“…we start with the assumption—which we claim, prima facie—that a relatively high degree of intra-regional economic interdependence—or its pursuit—has acted as the key driver, however (un)consciously, in the construction of regionalisms.…”[16]

Moreover, there is significant potential for intra-Atlantic trade to rise further if the Southern Atlantic actively pursues pan-Atlantic regional economic cooperation.

This is particularly relevant now, as partial deglobalization intensifies due to early geoeconomic decoupling, driven by the reshoring, friendshoring and nearshoring of production and supply chains. These shifts have been catalyzed by trade wars, the pandemic, the Ukraine War, Western sanctions on Russia, intensifying U.S.-China technological rivalry, and, more recently, the Gaza-Israel conflict. This conflict is already escalating into a broader conflagration, threatening to engulf the wider Middle East and, most critically, the Red Sea—an increasingly vital geostrategic fault line between Asia and the Atlantic Basin.

This emerging countertrend has the potential to reverse the earlier growth in extra-Atlantic economic connections for both Northern and Southern Atlantic countries. It also creates a strong incentive to explore new pan-Atlantic cooperation to address regional economic challenges and seize emerging opportunities.

The Challenge and Opportunity of Southern Atlantic Economic Ties

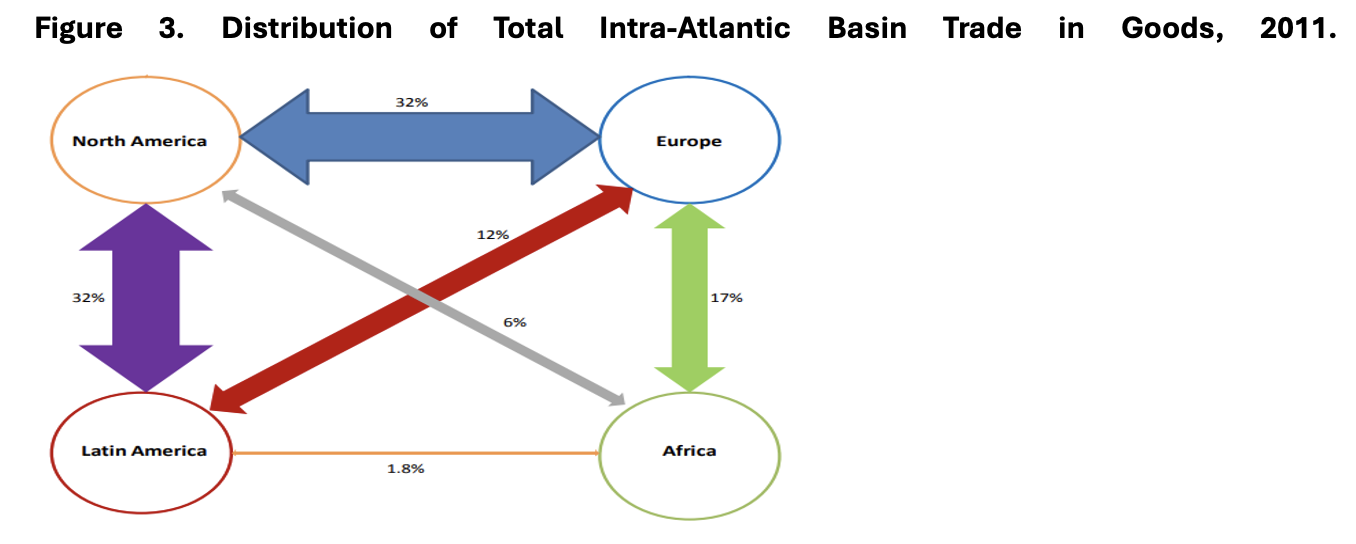

It is essential to recognize that intra-regional trade within the conceptual Atlantic Basin region remains dominated by two primary exchange vectors:

- Northern Atlantic trade (North America-Europe), and

- All-America North-South trade (U.S./Canada-LAC) (blue and purple, respectively, in Figure 3).

These dominant intra-Atlantic trade flows maintain similar relative volumes, with each accounting for nearly one-third of all intra-Atlantic Basin trade. Meanwhile, other trade vectors—such as the North-South vector of Europe-Africa trade (green), the diagonal Northeast-Southwest Europe-LAC trade vector (red), and the Africa-North American diagonal trade vector (grey)—are significantly less developed, representing 17%, 12% and 6% of total intra-Atlantic Basin trade, respectively, in descending order.

Finally, the South-South LAC-Africa trade vector (orange) across the Southern Atlantic remains negligible, accounting for just 2% of total intra-Atlantic Basin goods trade, compared to 32% within the Northern Atlantic and between the Americas. However, this South-South vector is inherently rich with untapped potential.

Based on UNCOMTRADE data. Source: Lorena Ruano, Jean Monnet Chair, CIDE, Mexico City Merchandise Trade in the Atlantic Basin, The Atlantic Basin Initiative, 2013. https://archive.transatlanticrelations.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Doc-9-Atlantic-Basin-Initiative-DR-background-paper-commerce-merchandise-trade-ruano.pdf

Western reshoring, friendshoring and nearshoring of production previously offshored by U.S. and European investments in Eurasia, particularly in China, present new opportunities for deeper intra-Atlantic Basin trade, encompassing both North-South and South-South exchanges. However, as explored below, the Southern Atlantic holds significant untapped potential that could be realized, especially if it actively participates in pan-Atlantic cooperation and moves toward Atlantic Basin regionalism.

A notable acceleration in intra-Southern Atlantic trade growth—particularly between LAC and Africa—could also be catalyzed by the ongoing development of the BRICS Plus framework. A strategy of geostrategic hedging by the Southern Atlantic states and societies, both as individual nations and as a collective (similar to ASEAN), could enable them to engage with both BRICS Plus and pan-Atlantic cooperation. This dual engagement has the potential to drive a multifaceted Southern Atlantic renaissance, encompassing production, trade, technology, cultural exchange, and the building of regional consciousness.

The Southern Atlantic’s strategic advantage at this historical moment lies in the simultaneous opportunities for deeper integration into the BRICS sphere and active participation in pan-Atlantic cooperation and emerging Atlantic Basin regionalism. This convergence of opportunities should appeal to both realist and liberal perspectives, highlighting the region’s potential for growth and collaboration.

X-shoring[17] and Pan-Atlanticism

Nascent Economic Fragmentation: Reshoring, Friendshoring, and Nearshoring

The slowing of globalization, growing geoeconomic fragmentation, and emerging strategic decoupling became evident during the Trump trade wars and the pandemic. However, it was not until the outbreak of the war in Ukraine in February 2022 that the geographic rearticulation of supply chains, spurred by these unexpected shocks, became more pronounced. Initially, this reconfiguration was largely a corporate ‘de-risking’ effort—a defensive strategy predominantly employed by Northern Atlantic companies.

After two years of pandemic-induced supply chain bottlenecks and the resulting cost-push inflation, corporate policies shifted. Risk management became a higher priority than cost-effectiveness, prompting many Northern Atlantic manufacturers to diversify their supply chains. This shift often took the form of a “China plus 1” or “China plus many” strategy,[18] where companies maintained some operations in China to serve its domestic market but sought to expand into emerging market countries with untapped manufacturing capacity.

Reshoring, nearshoring, and friendshoring (collectively referred to as ‘x-shoring’) emerged as key strategies to enhance supply-chain resilience. These approaches were designed to mitigate the risks associated with long, complex global supply chains, particularly those involving China, by creating redundancies and diversifying production options.

Initially, this corporate de-risking approach to friendshoring kept much Western investment in Asia, though a notable portion also flowed into Mexico.[19] However, the supply chain disruptions caused by the Ukraine-Russia war, along with the Western sanctions on Russia and China that followed, elevated supply chain rearticulation from a corporate risk management issue to a matter of national security. U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen highlighted this shift by advocating for the “friendshoring” of supply chains as a strategy to modernize U.S. trade policy, deepen economic integration, and enhance efficiency.[20] Corporate decisions, once focused solely on cost and efficiency, began to increasingly factor in political considerations that had previously been overlooked.

Depending on the availability of production factors and locations, this new corporate-political mix of motives could lead to a modular reconfiguration of various segments of many supply chains, particularly in high-tech and security-sensitive sectors, though not exclusively. Geopolitical events of recent years suggest that economic integration with trusted countries—and, to some extent, with those that are geographically closer and more strategically aligned—could reduce the risks posed to the economy, not only from general supply chain vulnerabilities (such as natural disasters, accidents and pandemics) but also from more specific and potentially enduring forms of “flow insecurity” arising from intensifying global geostrategic competition (e.g., those resulting from sanctions).

Countries that stand to benefit from this ongoing reconfiguration of global trade and investment will need to offer a combination of competitive labor costs (or at least available human capital and physical infrastructure), strategic proximity to Northern Atlantic countries (or at least not being in clear adversarial rivalry), and a strategic geographical location (i.e. relative proximity and/or reduced vulnerability to flow insecurities).

This potential underlying reconfiguration of global flows would provide a clear strategic impetus and geographic structure to the “regionalization of globalization”—the second potential outcome of Kortunov’s third scenario of “revolution” in the governance structure of the international system, as analyzed in the previous Brief (No. 6) in this series.

Hemispheric Economic Fragmentation: Initial Driver of Supply Chains into the Southern Atlantic

While the Red Sea route remained unimpeded, even as national security and strategic concerns began to shape x-shoring strategies and supply chain rearticulation, most of the shifts were—and would continue to be—toward the Northern Atlantic Plus (such as European countries and Mexico, but primarily trusted Asian partners), rather than the Southern Atlantic.

Nevertheless, the Israel-Gaza-Palestine war has generated multiple ripple effects across the global system, imbuing the corporate motives and national security imperatives behind the rearticulation of global supply chains with a clear ‘geopolitical’ character—emphasizing the ‘geo’ aspect of the word (i.e., the geography of actual global flow circuits). Friendshoring from China and Russia, for instance, to anywhere in Eurasia-Pacific east of Bab Al-Mandab, the Red Sea, and the Suez Canal is increasingly becoming obsolete as an ‘x-shoring’ strategy. This is due to the disturbances caused by Houthi militants, who have disrupted the passage through the Red Sea for any traffic perceived to be connected to or complicit with Israeli actions in Gaza. Moving forward, a variety of state and non-state actors could provoke similar disturbances.

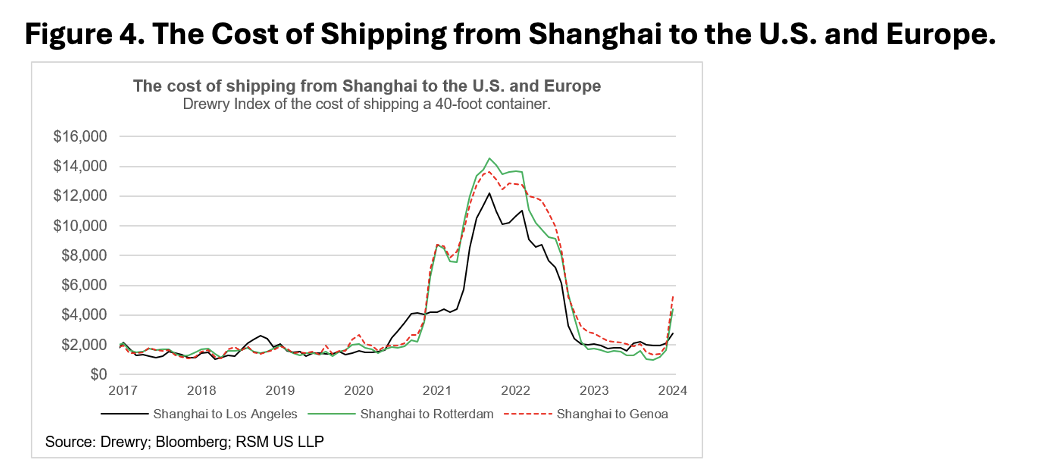

Houthi intervention in the Israel-Gaza war has had significant knock-on effects on shipping and other supply-chain-related costs. Shipping costs saw a significant increase in 2021-22 (sparked by the pandemic, the Ukraine-Russia war, and related sanctions), and again in 2023-24 due to the Israel-Gaza War and the Houthi response in the Red Sea (see Figure 4). Shipping costs from Rotterdam to New York are now lower than in 2019, and 45% lower than the Shanghai-Los Angeles haul.[21] The rise in energy prices, both pre- and post-Russian invasion of Ukraine, has only added to the pressure to shorten supply routes and regionally rationalize supply chains.

If the Houthis continue their targeted attacks on Israel-related shipping in the Red Sea, and should the Gaza War expand across the Middle East as it seems to be doing, further increases in energy prices are likely to occur. These disruptions would exacerbate the tendency toward economic fragmentation between Eurasia and the Atlantic Basin, further stimulating the trend for Northern Atlantic supply chains to retrench and rearticulate within the broad Atlantic Basin. This is particularly relevant for the strategic and commercial development of an Atlantic Basin LNG system, but also has significant implications for access to energy and critical minerals across varied societies within the Atlantic Basin. These societies often have different, yet increasingly interlocking, economic, political, sustainability, and geostrategic interests.

Source: Joseph Bruseulas, “Friend-Shoring and a New Era of U.S. Trade,” Real Economy, January 19, 2024 (https://realeconomy.rsmus.com/friend-shoring-and-a-new-era-of-u-s-trade/)

Under these new geopolitical circumstances—particularly the recent geographic dynamics influencing the international system—assessing the profitability and strategic desirability of an ‘x-shoring’ strategy should involve a more nuanced approach. This includes:

1- Increased focus on geographic realities: Greater attention must be paid to the geographic aspects of the geopolitical map, especially factors directly affecting shipping routes, trade flows, critical infrastructure, and flow circuits, including subsea cable networks.

2- Moving beyond a binary logic: The simplistic choice between ‘offshoring’ (relocating production abroad) and ‘reshoring’ (bringing it back home) should be abandoned.

3- Adopting a flexible and diversified approach: A more flexible strategy should combine not just ‘friendshoring’—which typically prioritizes the Northern Atlantic Plus and trusted Asian partners like ASEAN countries and India—but also consider ‘nearshoring’ opportunities west of the Suez Canal. This would favor the Atlantic Basin, with particular emphasis on the Southern Atlantic.

Such a geographically-conscious and flexible x-shoring strategy by the Northern Atlantic countries and corporations would require a strategic reorientation. This could lead to a far-reaching reconfiguration of existing supply chain networks, going beyond the earlier, simpler conception of ‘friendshoring’, which primarily looked to Asian allies and partners.[22]

Given that x-shoring strategies could increasingly be driven not only by corporate and national security concerns but also by geopolitical risks specific to the Asian-Middle East-Horn of Africa shipping chokepoints, modular reconfigurations of supply chains could conceivably shift toward the Atlantic Basin, particularly the Southern Atlantic. Such a development would counteract the ongoing shift of the global economic center of gravity toward China and Eurasia, while simultaneously increasing intra-regional Atlantic Basin trade. This shift would also intensify the participation of Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean in Atlantic Basin economic interactions, potentially mitigating the lingering North-South divide.

Strategic ‘Atlantic Basin-Shoring’

Some analysts are skeptical that current x-shoring trends alone can drive significant investment, technology transfer, production, trade, or employment into the Southern Atlantic.

As previously noted, many argue that the intensity of x-shoring ultimately provoked by broader threats to the flow security of global value chains will likely remain contained within the Asian Hemisphere. This perspective is rooted in the belief that while corporate de-risking strategies—aimed at mitigating disruptions from natural disasters, extreme weather, rising sea levels, and Black Swan events like the pandemic—may require diversification and redundancy across various sectors, there is little commercial incentive to significantly retrench supply chains to the Atlantic Hemisphere as long as Asian partners remain viable options.

Moreover, x-shoring driven by intensifying strategic competition—manifested in trade and broader geoeconomic conflicts between major and emerging Eurasian powers and the wider Western block of the Northern Atlantic Plus—would likely result in supply chain adjustments confined to a narrow range of highly strategic sectors. These include advanced semiconductors, dual-use technologies, and critical materials. Even within these sectors, reconfigurations would be costly and time-intensive, further reinforcing the notion that such shifts would predominantly benefit the Northern Atlantic Plus. On the other hand, certain human-induced threats to the corporate profitability and national security of supply chains could provoke more substantial rearticulation of supply chains back into the Atlantic Basin. Chief among these are the escalating risks of geopolitical disruptions along a ring of vulnerable geographic chokepoints encircling the Eurasian continent. These chokepoints amplify the impacts of the incipient decoupling and could significantly influence global supply chain flows.

The first critical segment of this global sea-lane runs through th e East China Sea, the Taiwan Strait, the South China Sea, and the Strait of Malacca. One major branch extends through the Strait of Hormuz into the Persian Gulf. Another, however, continues westward, traversing Bab al-Mandab, the Red Sea, and the Suez Canal into the Eastern Mediterranean—a region that increasingly represents a volatile geopolitical fault line dividing the Asian and the Atlantic hemispheres.

Thus, x-shoring driven solely by corporate logic could leave the Southern Atlantic largely unaffected. Even when intensified by geostrategic competition, friendshoring would likely only partially reroute supply chains across Asia, Australasia, and into the Northern Atlantic.[23] The full potential for the Southern Atlantic to participate in this reconfiguration of global supply chains emerges only when all three drivers—corporate profitability, renewed strategic competition, and the geographic and geopolitical realities of the global map—align to create a more comprehensive economic regionalization of supply chains within the broader Atlantic Basin. “Near-shoring or friend-shoring will likely play a larger part in shaping the narrative around global economic competition and collaboration”, as one close observer noted.[24]

China’s dual strategy—offshoring across the Belt and Road Initiative (including into the Southern Atlantic) and pursing ‘partial strategic decoupling’ through the BRICS sphere—further underscores the need to move beyond narrow efficiency- and risk-focused x-shoring strategies. Instead, a strategy that incorporates geographic and regional frameworks alongside corporate and national security imperatives could reorient x-shoring toward the Southern Atlantic.

Pan-Atlantic cooperation offers a unique opportunity to align the economic and sustainability goals of the Southern Atlantic with the de-risking and strategic competition of the Northern Atlantic. Such cooperation should aim to expand the Northern Atlantic’s x-shoring strategy beyond simple friendshoring and reshoring, integrating additional strategic objectives:

1- Strengthening Southern Atlantic economies.

2- Enhancing Southern Atlantic participation in Atlantic Basin economic interactions.

3- Building the capacity of Southern Atlantic nations to contribute meaningfully to pan-Atlantic collaboration on shared challenges and opportunities.

These efforts could address key thematic issues such as maritime and human security, the sustainable development of the blue economy, and the harnessing of blue carbon and nature-based solutions to combat climate change.

Economic Costs of Decoupling, Regional Fragmentation and New X-Shoring Dynamics

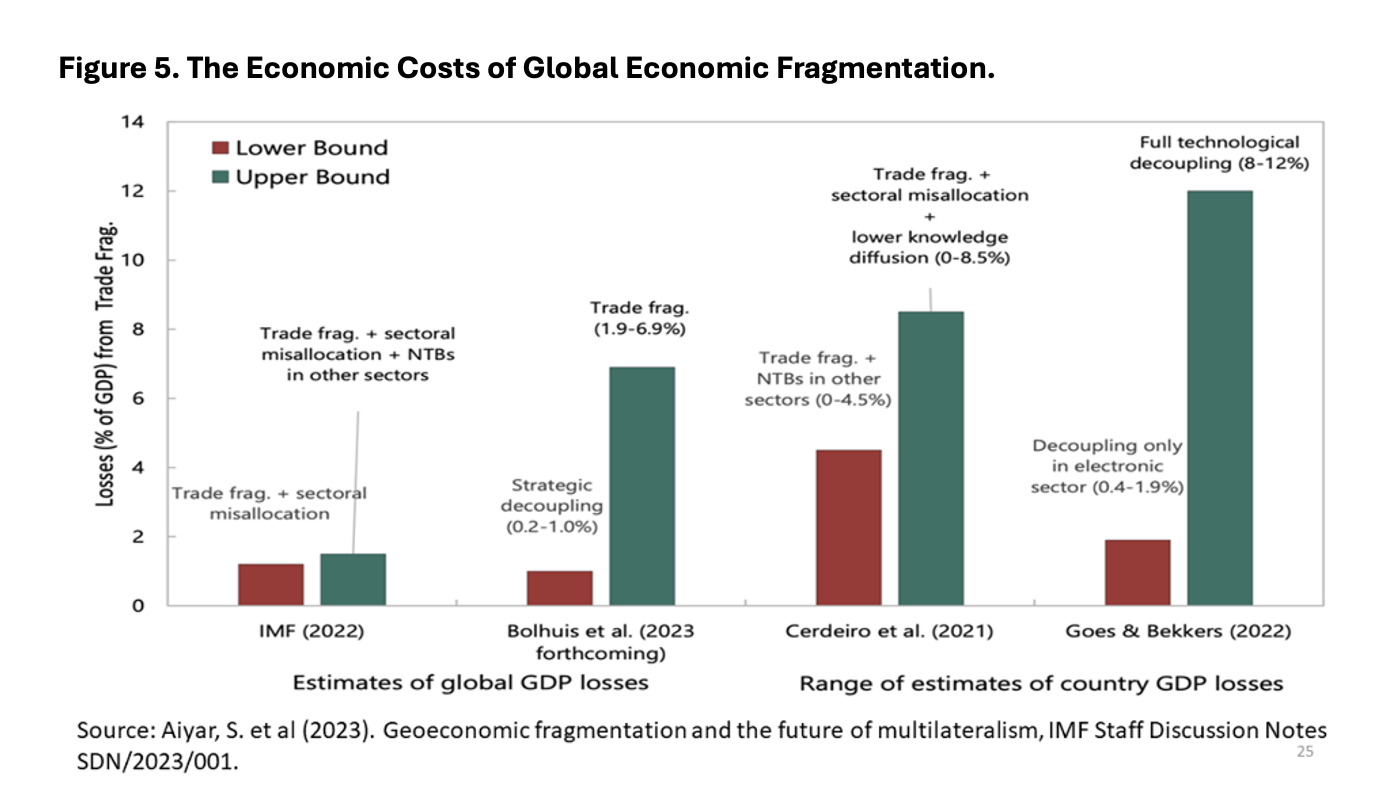

An integrated x-shoring strategy must account for the significant economic costs that any shift toward new economic configurations will entail. Estimates suggest that up to 26% of global exports—valued at approximately US$ 4.6 trillion—could be relocated in the coming years.[25] U.S. trade patterns already reflect this shift: trade with allies such as the EU, the UK, Japan and South Korea (collectively referred to as the Northern Atlantic Plus) is now five times greater than U.S.-China trade.[26]

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) projects that the emergence of economic blocks with higher barriers to FDI could lead to a 2% reduction in long-term global economic output.[27] Other studies estimate the economic costs of regional fragmentation and geostrategic decoupling—essentially the reverse of the efficiency gains of globalization—at between 1% and 12% of global GDP, depending on the scope and assumptions of the scenarios analyzed (see Figure 5).[28]

Cited in Otaviano Canuto, “Growth Implications of a Fractured Trading System”, PCNS, Sept 21, 2023 (https://www.policycenter.ma/publications/growth-implications-fractured-trading-system).

The Atlantic Basin: The Liberal ‘Second Best’ Solution

From a liberal perspective, the concept of an Atlantic Basin Community—anchored in pan-Atlantic regional cooperation—represents a pragmatic ‘second best’ alternative to the faltering UN-Bretton Woods global governance system. This system, increasingly unable to adapt to the realities of a multipolar world, struggles to maintain its foundational liberal principles while accommodating the shifting dynamics of international power.

In this context, pan-Atlantic cooperation offers a practical framework for rearticulating Northern Atlantic supply chains across the broader Atlantic Basin, incorporating strategic nearshoring in Africa and LAC.

At the same time, pan-Atlantic regionalism could appeal to realists, particularly in the Northern Atlantic, as a diplomatic and geoeconomic counterweight to the region’s growing relative isolation. This isolation stems from geoeconomic warfare—marked by selective East-West economic decoupling—and the rise of economic multipolarity, which diversifies global production more widely and relatively away from the West. These dynamics are increasingly shaped by an expanding BRICS Plus ‘transcontinental region,’[29] which could potentially encompass all regions except the Northern Atlantic. Nevertheless, this megaregional formation may still include much of the Southern Atlantic and is already beginning to take on a formal structure.

A return to a bipolar system is a real possibility. In the context of ongoing global realignment driven by emerging multipolarity and the erosion of unipolarity, the international system could stabilize around three possible configurations:

1- Neo-bipolarity: A U.S.-China rivalry, with a fragmented alignment of ‘friends’ and ‘allies’ on either side. This dynamic lacks a cohesive regional structure (beyond ‘East vs. West’) and bears a resemblance to the ‘classical bipolarity’ of the Cold War era.

2- Lop-sided bipolarity: The broader BRICS sphere, including the Southern Atlantic, opposing the Northern Atlantic Plus—essentially a bloc of ‘multipoles’ confronting the limited geography, resources, and population of a ‘unipolar alliance’.

3- Neo-classical bipolarity: In this scenario, an Atlantic Basin region takes shape to counterbalance the bulk of Eurasia, pulling many of the countries of the Southern Atlantic away from the exclusive gravity of the BRICS-sphere and drawing them into the Atlantic Basin through broadening and deepening of pan-Atlantic cooperation.

In all these scenarios, the Pacific Basin would remain split and contested, but the Atlantic Basin could achieve further integration and articulation as a distinct regional system, particularly under the third scenario of neo-classical East-West bipolarity.

This analysis suggests that both realism and liberalism within the Atlantic Basin can pragmatically converge to support pan-Atlantic cooperation and Atlantic Basin regionalism as a second-best strategy for pursuing a range of diverse yet interlocking strategic objectives among Atlantic Basin actors.

Morocco, the AASP and Nearshoring in the Southern Atlantic

Morocco holds significant potential in shaping the future of pan-Atlantic economic cooperation. The Kingdom has already pioneered two key Atlantic initiatives:

- The Atlantic African States Process (AASP): Aimed at fostering subregional cooperation on maritime and sustainable development challenges along Africa’s Atlantic coast.

- The Royal Atlantic Initiative: Designed to provide landlocked Sahel and Sahara countries with infrastructural and economic links to the Atlantic.[30]

These initiatives lay a strong foundation for Morocco and its Atlantic African partners to develop strategies for channeling friendshoring and nearshoring into the Southern Atlantic. The AASP could begin by launching a project to study the potential for Atlantic African states to participate in nearshoring. Building on this, the AASP could propose to the Partnership for Atlantic Cooperation (PAC) and the Atlantic Centre the establishment of a working group on pan-Atlantic cooperation. This group would aim to integrate the Southern Atlantic into Northern Atlantic x-shoring strategies.

Not only would such a project serve as a geoeconomic tool for advancing the regional grouping’s economic development and sustainability objectives, but it would also strengthen links across the Southern Atlantic between the AASP and other established Atlantic African and Southern Atlantic regional associations, such as the Friends of the Gulf of Guinea and ZOPACAS (the South Atlantic Zone of Peace and Cooperation). By spearheading efforts to explore the potential for pan-Atlantic cooperation to channel Northern Atlantic x-shoring into the Southern Atlantic, Morocco and the AASP would catalyze the integration of sub-basin regional cooperative organizations into a broader and more interconnected web of Atlantic Basin cooperation.

Another strategic action that Morocco and the AASP could take to positively influence the Atlantic Basin, with significant benefits for Southern Atlantic states, would involve leadership in the PAC. Should the U.S. withdraw from the PAC under the recently inaugurated Trump administration—or leave it inactive without leadership or direction—Morocco and its Atlantic African partners should urge the remaining signatories to sustain the structure for pan-Atlantic cooperation. Much like the Pacific Basin partners of the U.S.-led Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) who continued the process as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) after the first Trump administration’s withdrawal, the Atlantic Basin partners of the PAC should persist with the process even in the absence of U.S. participation.

Conclusion

From a liberal internationalist perspective, the prospect of pan-Atlantic cooperation and Atlantic Basin regionalism is driven by numerous political motives and economic incentives. Some of these drivers have been evolving since the start of the century, including the unique and shared marine environmental and maritime security challenges and opportunities linked to the Atlantic Ocean. Others—overlapping with realist considerations—have been catalyzed by the recent intensification of multipolarity, geostrategic competition, and the ongoing global realignment currently in flux.

The pan-Atlantic agenda could initially focus on ocean-based cooperation, particularly addressing climate change issues as outlined in the action plan of the PAC. It could then progressively expand to include broader areas of human and maritime security cooperation, which the Atlantic Centre initiative has already identified as priorities. Over time—given the impasse at the WTO, the growing concerns with ‘de-risking’, near- and friendshoring, strategic decoupling, and geoeconomic fragmentation—a pan-Atlantic regional economic agreement is likely to be proposed. This development would parallel the creation of Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) for the Pacific Basin in the late 1980s, albeit under very different, even opposing, dynamics.

To ensure sustainable prosperity, any pan-Atlantic economic cooperation must be carefully designed to genuinely attract Southern Atlantic partners, whose strategic importance and influence are rising alongside their growing skepticism of Northern Atlantic liberalism. Instead of advancing an ambitious ‘behind-the-border’ and WTO+ agenda that primarily serves Northern Atlantic interests (such as an extended TTIP encompassing the entire basin), a more pragmatic approach would involve crafting a pan-Atlantic regional economic agreement that offers preferential trade and investment treatment to Southern Atlantic countries.[31] Alternatively, even a framework for harmonizing existing Preferential Trade Agreements (PTAs) across the Atlantic could garner greater interest from Africa and Latin America.

Moreover, a pan-Atlantic trade agreement that includes agriculture could hold particular appeal for certain Southern Atlantic countries.[32] Such an agreement would finally enable Latin America to capitalize on its comparative advantages in agriculture within the context of ‘intra-Atlantic Basin’ trade. Most importantly, as previously mentioned, a cooperative mechanism to channel nearshoring and friendshoring investments from Eurasia to Africa and Latin America could be a proposal worth serious consideration within a pan-Atlantic framework today. Pan-Atlantic cooperation is already being explored in one critical dimension of this geostrategic x-shoring dynamic: the reconfiguration of the diverse and multifaceted critical minerals supply chains. To offer a more coherent geostrategic approach in the context of a new ‘regionalization of globalization’, the initial working group of the Atlantic Energy Forum (AEF) has proposed an ‘Atlantic Critical Minerals Partnership’.[33] This initiative aims to serve as a more rational strategic alternative to the Minerals Security Partnership (MSP) of the Northern Atlantic Plus countries.

The AEF has also highlighted the potential for broader pan-Atlantic cooperation through the development of newly emerging Atlantic Basin systems that could facilitate greater economic interaction and integration across the entire basin. These systems could play a key role in enabling strategic x-shoring into the Southern Atlantic. Some of these include:

- A new Atlantic Basin LNG system: This system builds upon the recently developed LNG network linking the U.S. and Europe, extending it to integrate with the Southern Atlantic. Under the Milei government, Argentina is poised to play a pivotal role by fully developing its Vaca Muerta shale resources and investing in the necessary pipeline and LNG infrastructure to contribute significant LNG volumes to the basin.

- Atlantic Island energy systems: These systems could serve as laboratories for clean energy and sustainability transitions across the Atlantic Basin.

A network of fiber optic and subsea digital cables: Driven by Atlantic Basin investment, this network is rapidly expanding, criss-crossing the basin and lining its continental coastlines to create an increasingly dense and interconnected Atlantic digital infrastructure.

- An Atlantic Basin system of ports and transportation infrastructure: This includes maritime and terrestrial hinterland infrastructure, multimodal transportation networks, logistics hubs, and clean energy systems. Together, these components could be unified under a pan-Atlantic cooperative framework.

All these emerging or proto-systems present ripe opportunities for the articulation of pan-Atlantic cooperation. While the PAC primarily focuses on ocean science capacity building, data exchange, and maritime climate concerns, significant potential remains for broader collaboration. This could include addressing climate finance challenges—such as the potential establishment of an Atlantic Basin Debt-for-Climate Swap Agreement—as well as advancing initiatives for the protection and restoration of high seas marine and coastal ecosystems. Additionally, feasible and effective pan-Atlantic regulatory cooperation could be explored to ensure sustainable management of shared resources. A potential Atlantic Basin Blue Carbon Market could also be explored as part of this broader cooperative agenda.

All these possibilities, and more, will be examined in subsequent Policy Briefs as part of the ongoing series Pan-Atlanticism: The Atlantic Basin in a Multipolar-Transnational World.

[1] Paul Isbell, “Liberalism and Pan-Atlanticism (I): Realism versus Liberalism in the Atlantic Basin”, Policy Center for the New South, October 2024, PB-49/24 (https://www.policycenter.ma/publications/liberalism-and-pan-atlanticism-i-realism-versus-liberalism-atlantic-basin).

[2] Paul Isbell, “Liberalism and Pan-Atlanticism (II): Liberalism, Regionalism and the Atlantic Basin”, Policy Center for the New South, October 2024 PB-50/24 (especially Table 1) (https://www.policycenter.ma/publications/liberalism-and-pan-atlanticism-ii-liberalism-regionalism-and-atlantic-basin).

[3] See Paul Isbell, “The Rising Strategic Significance of the Atlantic Basin: An Emerging Pan-Atlanticism”, Policy Center for the New South, December 14, 2023, PB-44/23 (https://www.policycenter.ma/publications/emerging-pan-atlanticism).

[4] See Paul Isbell, “The Strategic Significance of Pan-Atlanticism for the West”, Policy Center for the New South, December 19, 2023, PB45/23 (https://www.policycenter.ma/publications/strategic-significance-pan-atlanticism-west?page=1);“The Strategic Significance of Pan-Atlanticism for the Rest”, Policy Center for the New South, December 28, 2023, PB-48/23 (https://www.policycenter.ma/publications/atlantic-basin-realism-andgeostrategy-ii-strategic-significance-pan-atlanticism-rest); “The Strategic Significance of Pan-Atlanticism for the Southern Atlantic”, Policy Center for the New South, January 3, 2024, PB-01/24 (https://www.policycenter.ma/publications/strategic-significance-atlantic-basin-and-pan-atlanticismsouthern-atlantic).

[5]See Paul Isbell, “Liberalism and Pan-Atlanticism (I): Realism versus Liberalism in the Atlantic Basin”, op. cit., and “Liberalism and Pan-Atlanticism (II): Liberalism, Regionalism and the Atlantic Basin”, op. cit., (especially Table 1)

[6] See the White Paper of the Atlantic Basin Initiative’s Eminent Persons Group, “A New Atlantic Community: Generating Growth, Human Development and Security in the Atlantic Hemisphere”, Atlantic Basin Initiative (Washington, DC. Johns Hopkins University SAIS, Center for Transatlantic Relations/Brookings Institution Press, 2014).

[7] See Len Ishmael, “A World Divided: A Multilayered, Multipolar World,” in Len Ishmael, ed., Aftermath of War in Europe: The West vs. The Global South? Policy Center for the New South, December 2022, pp. 17-41.

[8] Daniel S. Hamilton, “TTIP’s Geostrategic Implications,” Summary Chapter in The Geopolitics of TTIP: Repositioning the Transatlantic Relationship for a Changing World, Daniel S. Hamilton, ed., Center for Transatlantic Relations, Johns Hopkins University-SAIS, 2014, p. xv. https://archive.transatlanticrelations.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Complete_book.pdf

[9] The figures in this paragraph, and in Figure 1 and in Tables 1 and 2, refer to the ‘broad Atlantic Basin’, which includes not just Atlantic coastal and some landlocked states (as with the ‘intermediate Atlantic in Figure 2), but all of the countries of all four Atlantic continents.

[10] Data from UNCOMTRADE, 2012, as elaborated by Daniel S. Hamilton.

[11] The figures presented in Figures 1 and 2 refer to an ‘intermediate Atlantic Basin’ (defined as including all Atlantic coastal states and those landlocked countries in South America and Africa whose river basins and transport and commercial infrastructures lead primarily to the Atlantic). For the distinction between the ‘narrow’, ‘intermediate’ and ‘broad’ Atlantic Basin, see Paul Isbell, “The Rising Strategic Significance of the Atlantic Basin: An Emerging Pan-Atlanticism”, op. cit., p. 12.

[12] The figures presented in Figures 1 and2 refer to trade in ‘goods’. Nevertheless, the situation is similar with respect to trade in ‘services’, if not more pronounced. See Daniel S. Hamilton and Joseph P. Quinlan, The Transatlantic Economy 2024: An Annual Survey of Jobs, Trade and Investment between the United States and Europe, Foreign Policy Institute, Johns Hopkins University SAIS/Transatlantic Leadership Network, 2024, pp. 16-18 (of the Executive Summary) (https://transatlanticrelations.org/publications/transatlantic-economy-2024/).

[13] See Paul Isbell and Kimberly Nolan Garcia, “Latin America’s Interregional Reconfiguration: the Beginning or the End of Latin America’s Continental Integration,” in Interregionalism across the Atlantic Space, Frank Mattheis and Adreas Litseard, eds. Springer International Publishing, 2018.

[14] Paul Isbell and Kimberly A. Nolan Garcia, “Regionalism and Interregionalism in Latin America: The Beginning or the End of Latin America’s ‘Continental Integration?” ATLANTIC FUTURE Scientific Paper Number 20, European Commission, Brussels, 2015, p.14.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Paul Isbell and Kimberly A. Nolan Garcia, “Regionalism and Interregionalism in Latin America: The Beginning or the End of Latin America’s ‘Continental Integration?” ATLANTIC FUTURE Scientific Paper Number 20, European Commission, Brussels, 2015, p. 3.

[17] Some use the term “x-shoring” when the discussion or statement relates to all kinds of changes in the GVC, including reshoring, friendshoring and nearshoring. See, for example, Renato G. Flôres Jr., “Reshoring, Friendly-Shoring, Target-Shoring: Dreaming is Free but Development is Not”, FGV and Jean Monnet Network (2.0) of Atlantic Studies, June 2023 (https://www.jmatlanticnetwork2.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/fgv-reshoring-and-friendly-shoring-renato-g-flores-jr-1.pdf).

[18] Oleg Ruban, “Nearshoring, Friendshoring and Reshoring: Heads Up to Equity Allocators,” MSCI Blog, September 13, 2023 (https://www.msci.com/www/blog-posts/nearshoring-friendshoring-and/04065519030).

[19] Otaviano Canuto, “The U.S. Elections Will Have Worldwide Economic Consequences”, Commentary, Policy Center for the New South, September 2, 2024 (https://www.policycenter.ma/publications/us-elections-will-have-worldwide-economic-consequences).

[20] Günther Maihold, “A New Geopolitics of Supply Chains: The Rise of Friend-Shoring,” SWP Comment, No. 45, July 2022 https://www.swp-berlin.org/publications/products/comments/2022C45_Geopolitics_Supply_Chains.pdf

[21] See Joseph Bruseulas, “Friend-shoring and a new era of U.S. trade,” Real Economy, January 19, 2024 (https://realeconomy.rsmus.com/friend-shoring-and-a-new-era-of-u-s-trade/).

[22] Ruban, op. cit.

[23] Renato G. Flôres Jr., op. cit.

[24] Joseph Bruseulas, op. cit.

[25] Günther Maihold, “A New Geopolitics of Supply Chains: The Rise of Friend-Shoring,” SWP Comment, No. 45, July 2022 (https://www.swp-berlin.org/publications/products/comments/2022C45_Geopolitics_Supply_Chains.pdf).

[26] Joseph Bruseulas, “Friend-shoring and a new era of U.S. trade,” Real Economy, January 19, 2024 (https://realeconomy.rsmus.com/friend-shoring-and-a-new-era-of-u-s-trade/).

[27] JaeBin Ahn, Ashique Habib, Davide Malacrino and Andrea Presbitero. “Fragmenting Foreign Direct Investment Hits Emerging Economies Hardest.” IMF Blog, April 5, 2023.

[28] See Otaviano Canuto, “Growth Implications of a Fractured Trading System”, PCNS, Sept 21, 2023 (https://www.policycenter.ma/publications/growth-implications-fractured-trading-system).

[29] The BRICS Plus represents the pinnacle of a ‘third generation’ of regionalism that has emerged in the 21st century. This generation follows earlier regional ideological or strategic groupings, such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, the Eurasian Economic Union, UNASUR, and the ALBA alliance in Latin America, which were established with the aim of setting up new regional rules. In contrast, Atlantic Basin regionalism—exemplified by initiatives like the nascent Partnership for Atlantic Cooperation—could signal the emergence of a ‘fourth generation’ of ‘ocean basin regionalisms’. Preceding this development were efforts like the unsuccessful Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) and the now-defunct Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP).

[30] Rida Lyammouri and Amine Ghoulidi, “Morocco’s Atlantic Initiative: A Catalyst for Sahel-Saharan Integration”, Policy Center for the New South, PB-68-24, December 2024.

[31] One proposal, raised at the second Eminent Persons Group meeting of the Atlantic Basin Initiative (La Romana, Dominican Republic, January 18-19, 2013), is “to implement throughout the transatlantic area a common duty-free and quota-free treatment scheme for Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and low income African countries. At the moment there is a hodgepodge of different schemes with different rules and different country coverage in the US, the EU, Canada and Brazil. Their complexity reduces their value to poor countries with limited institutional capacity. A new initiative to harmonize trade preferences to poor countries could complement improvements in aid effectiveness and a new aid architecture.” Eveline Herfkens, “Pan-Atlantic Development Cooperation for the 21st Century”, Food-for-Thought Paper, Eminent Persons Group of the Atlantic Basin Initiative, Center For Transatlantic Relations, Johns Hopkins University SAIS, January 18, 2013 (https://archive.transatlanticrelations.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Doc-4-Atlantic-Basin-Initiative-DR-Food-for-Thought-Paper-Development-Herfkens.pdf). See also, Eveline Herfkens, “TTIP and Sub-Saharan Africa: A Proposal to Harmonize EU and U.S. Preferences”, Chapter 11 in The Geopolitics of TTIP: Repositioning the Transatlantic Relationship for a Changing World, Daniel S. Hamilton, ed., Center for Transatlantic Relations, Johns Hopkins University-SAIS, 2014, p. vii.https://archive.transatlanticrelations.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Complete_book.pdf

[32] See, for example, the benefits to Brazilian agricultural sectors and the net gains for the Brazilian economy from such a possible pan-Atlantic trade accord in Vera Thorstensen and Lucas Ferraz, “The Impact of TTIP on Brazil”, Chapter 10 in Daniel S. Hamilton, ed., The Geopolitics of TTIP: Repositioning the Transatlantic Relationship for a Changing World, Center for Transatlantic Relations, Johns Hopkins University-SAIS, 2014, p. xv. (https://archive. transatlanticrelations.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Complete_book.pdf).

[33] Under the auspices of the Atlantic Basin Initiative of the Foreign Policy Institute of Johns Hopkins University SAIS and the Transatlantic Leadership Network (transatlantic.org).