Publications /

Opinion

The issue of environmental degradation represents a significant global challenge. It manifests in various forms, including physical alterations such as air pollution, ozone depletion, climate change, marine pollution and biodiversity loss. These changes are proven to be linked to human activities, such as energy production and consumption, tourism and agriculture. Additionally, factors like population growth and health and safety concerns contribute to environmental decline.

Is Growth Good or Bad? Exploring Economic Theories on Sustainability

As the world grapples with environmental challenges, it is becoming increasingly clear that these issues are closely linked to national and international systems of production, distribution, and consumption. Traditional approaches to international political economy (IPE), such as economic nationalism, liberalism, and Marxism, have historically overlooked environmental concerns, including climate change. However, as time has gone by, these approaches have increasingly recognized the critical intersection between global environmental challenges and economic systems (Table 1).

Table 1: Traditional IPE Theories and the Environment

|

|

Insight |

Sustainable development |

Shortcoming |

|

Economic nationalism |

State interests will frustrate international agreements |

Unlikely, given desire for growth |

Unable to confront issue of unrestrained growth |

|

Liberalism |

Interdependence increases incentives for environmental agreements |

Better market signals will support it |

Blind to role of state and corporate power in environmental change |

|

Marxist, radical |

Northern vs. Southern interests, class interests |

Degradation caused by capitalism |

Ignores damage caused by socialist growth |

Source: O’Brien & Williams, 2016

From a nationalist economic perspective, achieving sustainable development hinges on its prioritization by states. However, this approach faces a critical challenge: reconciling economic growth with environmental protection. When prioritizing economic expansion, states often prioritize military and economic power over environmental concerns, as seen in the Trump administration’s withdrawal from the Paris Agreement and attempts to restrict climate science. Environmental concerns, thus, frequently get sidelined in favor of traditional political power objectives.

This perspective is skeptical of extensive environmental cooperation, as states are unlikely to champion sustainability unless it aligns directly with their own interests. For sustainable development to become a reality, states must perceive environmental policies as advantageous to their national goals. Efforts to promote sustainability will, therefore, fall short if economic growth remains the sole focus. Such a singular pursuit risks overlooking environmental concerns in favor of short-term economic gains.

Liberals argue that environmental degradation stems from market failure. Specifically, they point to the absence of mechanisms for accurately valuing natural resources. Their solution? To integrate environmental costs into pricing policies like carbon pricing, as seen in the European Union’s Emissions Trading System and Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism. This, they believe, would encourage efficient resource allocation and naturally incentivize environmental protection. For liberals, sustainable economic policies do not require that growth be stifled but rather that it be made sustainable. The issue is not growth itself, but its current trajectory. They view both economic growth and proper environmental valuation as essential tools for achieving sustainability.

While acknowledging the role of states, liberals recognize the limitations imposed by a complex web of global transactions and interdependencies. Therefore, they prioritize market-based solutions and the integration of environmental considerations into economic policies as the primary drivers of sustainable development. By valuing natural resources and incorporating environmental costs into pricing, liberals aim to strike a balance between economic growth and environmental protection.

Radical theorists identify capitalism’s exploitative nature as the root cause of environmental degradation. They argue that current economic practices embedded in this system create significant hurdles to implementing sustainable policies. For them, the core issue lies in the values driving capitalism. The emphasis on profit maximization and limitless growth, they contend, is inherently incompatible with sustainability.

These radical perspectives shed light on the deep inequalities and power imbalances within the international system. The developed nations, often referred to as the “North”, exert significant influence over decision-making processes. This power dynamic has historically led to a pattern of exploitation of developing countries in the “South”. International environmental negotiations serve as a stark illustration of this dynamic. The interests of the North often take center stage, while the concerns of the South, which often bear a disproportionate burden of environmental consequences, are frequently marginalized.

From the Rio Earth Summit to Carbon Pricing: A Brief History of International Action

The 1960s witnessed a surge in environmental awareness, marking a turning point in how the world approached environmental issues. Scientific discoveries like ozone depletion and environmental disasters like the Torrey Canyon and Chernobyl spills served as stark reminders of the urgent need to integrate environmental concerns into global political and economic discussions. This urgency was further amplified by the escalating consequences of climate change, particularly the accelerating rise in global temperatures. This was fueled by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports, which concluded with 95% certainty that human activity is the primary driver of global warming.

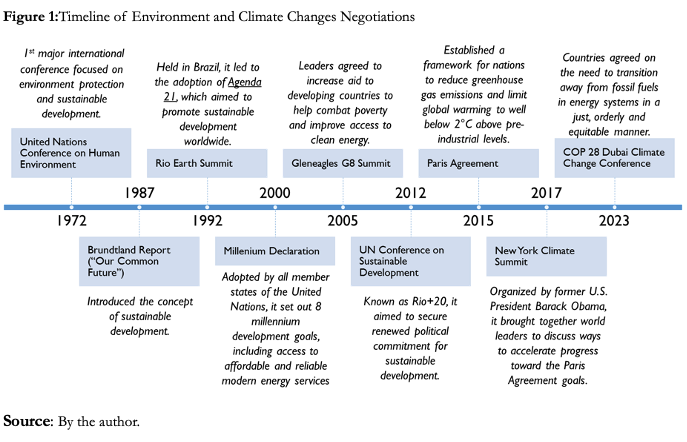

This period set the stage for later significant developments such as the 1992 Rio Earth Summit, which further solidified the recognition of environmental concerns as critical factors on national and international agendas (Figure 1). Following this summit, numerous international meetings and discussion forums were held at the global level, further advancing the climate change and environmental agenda. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) emerged as the primary forum for international climate negotiations. Within this framework, countries have collaborated on sharing emissions data, developing reduction strategies, and providing assistance to developing nations. To achieve these objectives, the States Parties to the UNFCCC have held regular meetings, known as Conferences of the Parties (COPs). Key milestones within the UNFCCC process include:

- 1997 Kyoto Protocol: This agreement, while established in 1997, only came into force in 2005. It distinguished between developed and developing countries, assigning binding emission reduction targets only to developed nations. It also introduced mechanisms like emissions trading to tackle GHG emissions. However, challenges like complex negotiations, the rise of emerging industrial polluters, and climate skepticism hampered its effectiveness. It was intended to remain in force until 2012, after which it would be replaced by a new, more effective agreement. However, it has proved difficult to negotiate a legally binding and acceptable post-Kyoto framework.

- 2015 Paris Agreement: Marking a significant breakthrough, the Paris Agreement aims to limit global warming to well below 2°C compared to pre-industrial levels, with efforts to limit it to 1.5°C. It encourages countries to develop national contributions (NDCs) for reducing greenhouse gas emissions and incorporates the concept of Common but Differentiated Responsibilities. While results remain mixed after nine years, the agreement represents a more inclusive approach compared to the Kyoto Protocol.

A critical strategy emphasized in the Paris Agreement is carbon pricing. This approach incentivizes countries to design market-based mechanisms that incentivize emissions reductions. These mechanisms aim to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by passing the cost of emitting on to emitters. This approach shifts the responsibility for paying for climate change damages from the general public to the producers of greenhouse gas emissions. Carbon pricing can thus promote cost-effective reductions in CO2 emissions, provide strong incentives for innovation, and improve governments’ fiscal positions by internalizing the associated externalities. Carbon markets and mechanisms have evolved steadily. The share of global emissions covered by carbon taxes and emissions trading systems (ETSs) has grown from 7% in 2013 to around 23% in 2023. Government revenues from carbon taxes and ETSs worldwide have also grown nearly five-fold as policies have evolved and diversified to reflect increased ambition.

However, this is an inherently complex policy instrument. Its effectiveness is debated, with some arguing that it fails to address the root causes of environmental degradation, while others warn against its potential regressive effects on low-income households. Indeed, by increasing the cost of carbon-intensive products such as energy and transport, low-income households bear a disproportionate burden of these increased costs relative to their income. This can exacerbate existing income inequalities and strain the finances of vulnerable groups.This reveals a crucial truth: Modern production and development methods, often seen as solutions to poverty, can exacerbate environmental degradation and threaten vulnerable populations. The burden of environmental degradation falls disproportionately on vulnerable populations, particularly in developing countries. Health problems, displacement, and increased poverty are some of the consequences they face, often exacerbated by inadequate international support and a lack of environmental justice considerations in economic planning.

But even with carbon pricing gaining traction, a crucial question lingers: Have we done enough to bridge the gap between environmental ambition and the practical realities of implementation, particularly when it comes to ensuring a just transition for vulnerable populations most impacted by climate change? The success of our efforts hinges on addressing this critical question. Only through a comprehensive approach that tackles both environmental and social inequities can we build a truly sustainable future.