Publications /

Opinion

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), launched by Xi Jinping, passed its tenth anniversary in 2023. It has entered a third phase.

The initiative added a label to China’s financing and construction of infrastructure abroad, which had already totaled more than $400 billion in the previous 10 years. In addition to the use of investment projects as part of Chinese ‘soft power’, the BRI has served to increase levels of usage of the country’s excess installed capacity.

China’s economic rebalancing beyond its overinvestment-based growth model of the decades before the global financial crisis has been implemented gradually, with real estate and infrastructure construction bubbles allowing it to go through a very gradual slide in growth rates, from double-digit GDP growth rates to 6% in 2019, the last year before the pandemic. BRI fit like a glove.

In addition to offering a source of investment for developing countries in dire need of infrastructure, the BRI was set out as a platform with rapid implementation and without much due diligence in relation to environmental, social, or governance standards. Furthermore, the BRI would reinforce what we called at the time an “overlapping” or “parallel” globalization to existing globalization, based on Chinese industry in this case.

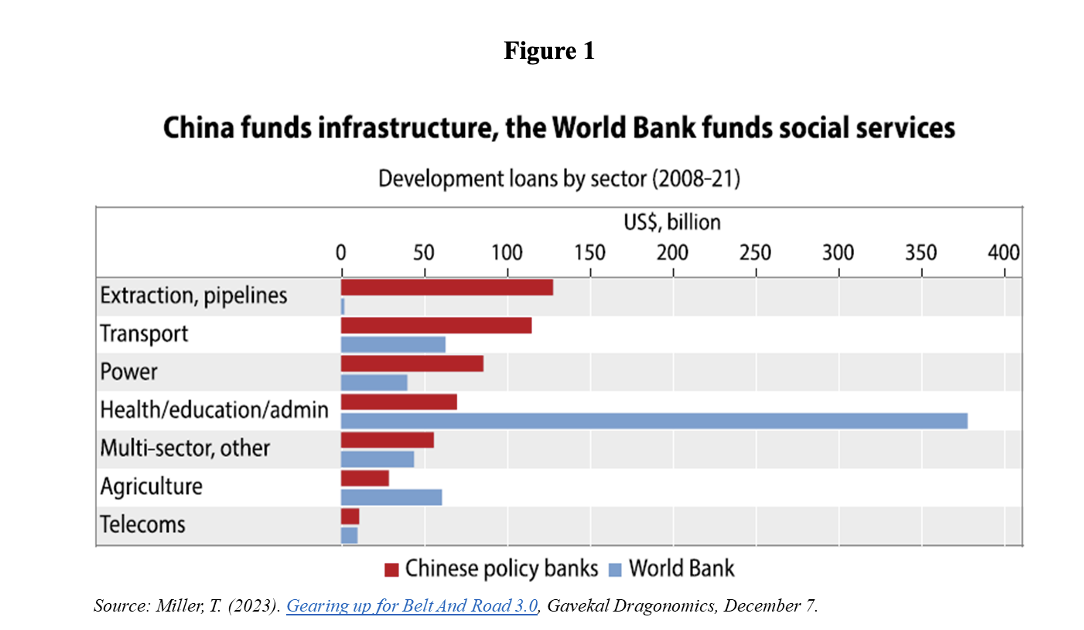

Indeed, China has become the largest bilateral source of international development financing. By 2018, mainly directed towards infrastructure and the energy sector, China’s development loans to Latin America and the Caribbean reached levels greater than the sum of loans from the World Bank, the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), and the Bank of Development of Latin America (CAF). The presence of such operations in the region came to be seen as a “competition for influence”. Something similar happened in Africa.

According to data collected by Boston University’s Global Development Policy Center (Figure 1), the volume of loans from Chinese public development banks—Exim and China Development Bank—surpassed those from the World Bank in the period from 2008 to 2021, in areas including oil extraction and pipelines, transport, energy, and telecommunications. The World Bank maintained its lead only in health, education, governance, and agriculture, in addition to direct budgetary support. In total for the period, loan commitments made by the two Chinese public development banks reached $498 billion, or 83% of the World Bank’s total ($601 billion).

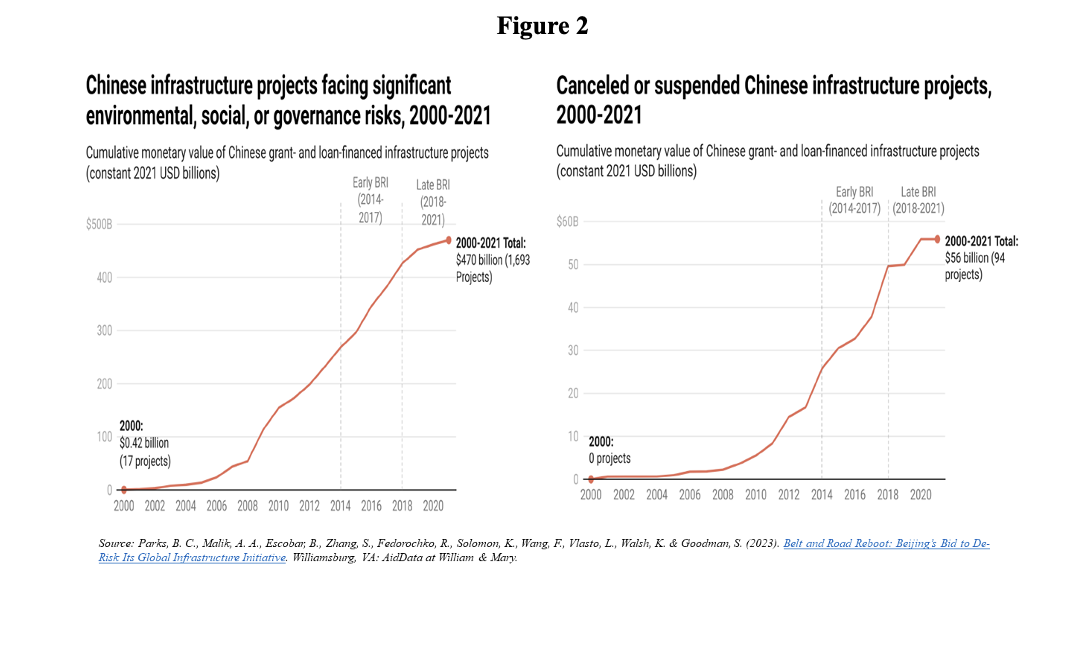

However, from 2018, there was a change. Volumes fell and the BRI entered a phase that can be called a “correction” (Parks et al, 2023; Miller, 2023). A brake was applied by imposing more demanding approval standards and shifting financing from Chinese official development banks to state-owned commercial banks. The downside of the laxity of standards with respect to environmental, social, and governance risks became increasingly clear, and the number of canceled or suspended infrastructure projects rose significantly (Figure 2).

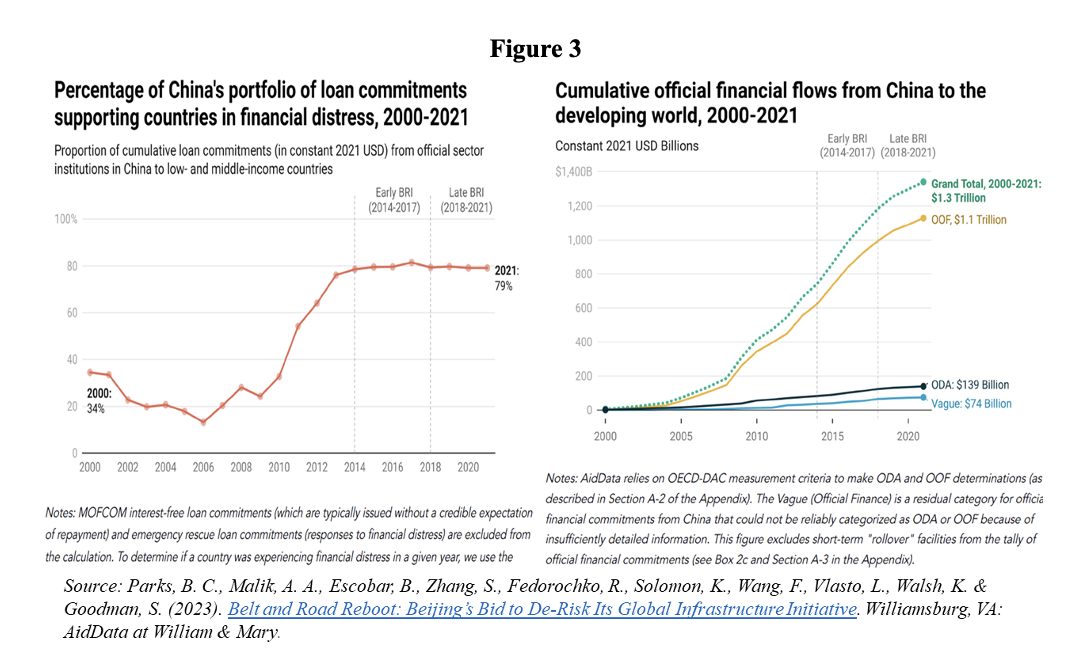

With many borrowing countries entering ‘debt distress’ situations, China’s central bank also opened emergency lines of credit. Strictly speaking, most of the resources since 2020 went to emergency loans to prevent several low- and middle-income countries from having to default on the service debt of previous projects, rather than to the financing of new projects (Figure 3, left panel).

Total debt owed to China by low- and middle-income countries is between $1.1 trillion and $1.5 trillion (Figure 3, right panel). About 80% of China’s loan portfolio is in countries currently experiencing financial difficulties.

In 2021, 58% of Chinese loans were bailouts, with less than a third for new infrastructure projects. More than half of the loans to low- and middle-income countries took the form of currency swap lines with China’s central bank or from the external reserve manager: the State Administration of Foreign Exchange Reserves. This year Argentina avoided defaulting with the International Monetary Fund thanks to the credit line between its central bank and the Chinese central bank.

More than half of China’s official BRI loans have already entered their principal repayment periods, with the share expected to reach 75% by 2030. This means that China’s debtors are beginning to make large repayments at a time when interest rates have risen, the U.S. dollar has appreciated, and global economic growth is slowing. As Parks et al (2023) put it, China is now transitioning from being the world’s largest bilateral development creditor to “the world’s largest official debt collector”.

China’s emergence as the world’s largest bilateral creditor and its insistence on bilateral debt restructuring processes on its own terms (which rarely include repayment of principal), without fully participating in multilateral processes, means that the resolution of the debt distress that developing countries are grappling with is expected to drag on for several years.

But after the ‘peak’ (2014-17) and ‘correction’ (from 2018) phases, the BRI seems to have entered a third phase, judging by the statements made by Chinese authorities during the Third BRI Forum in Beijing in October 2023. The focus will now be on “smaller, smarter” projects, in coordination with the country’s clean-energy industrial policies.

The BRI will now want to expand markets for Chinese solar and wind-energy manufacturers, in addition to ensuring access to critical minerals for its battery production value chain. Given the context of technological rivalry—including in clean energy—between China and the United States and its allies, a comparable reaction to the BRI in its third phase, if any, has yet to be seen.