Publications /

Opinion

If we want to understand the implications for growth—particularly the costs—of moving towards a fractured trading system, we can use as a benchmark what happened during the period of what is usually called hyper-globalization or globalization 2.0. Here, I'll try to highlight the relevant aspects, to use them as a benchmark to shine a light on the costs of increasing fragmentation of the trading system.

So, what was hyper-globalization or, as Professor Richard Baldwin from the Geneva Institute calls it, Globalization 2.0? In the nineteen-eighties and nineties, particularly the nineties, we saw the consequences of what one may call a tectonic shift under the global economy. This was the combination of three things:

First, a cluster of technological innovations, not only in information and communication technology but also in transportation. Containerization allowed manufacturing processes to be broken down to levels previously unthinkable.

Second, the reasonably widespread adoption of trade liberalization policies. In most countries, particularly developing countries, there was a move in favor of reducing tariffs and non-tariff barriers to trade.

Third, the incorporation, almost overnight, of 1 billion workers with lower wage aspirations into the global supply of labour available for market economies. I'm referring here not only to the collapse of eastern European communist regimes but also to Chinese President Deng Xiaoping's creation of special economic zones that facilitated a tremendous rise in exports and imports as a share of China’s GDP.

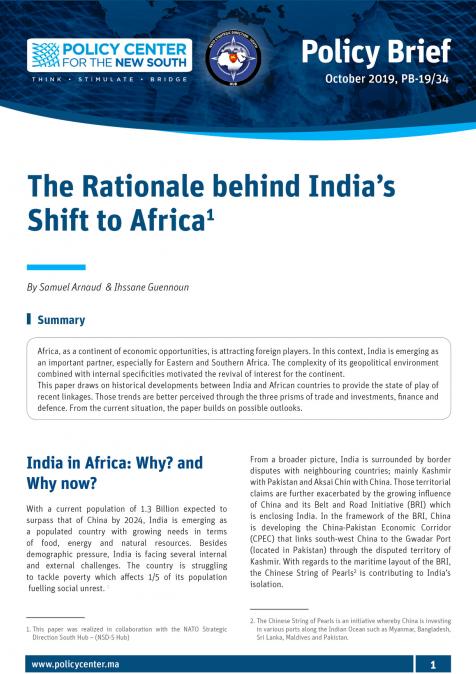

The results? Well, there was substantial growth in GDP per capita in emerging markets and developing economies. The correlation between trade insertion in exports and increases in GDP per capita can be seen in Chart 1. And there was a change in the composition of the global economy and trade, with the rising weights of not only China, but also other emerging markets and developing economies.

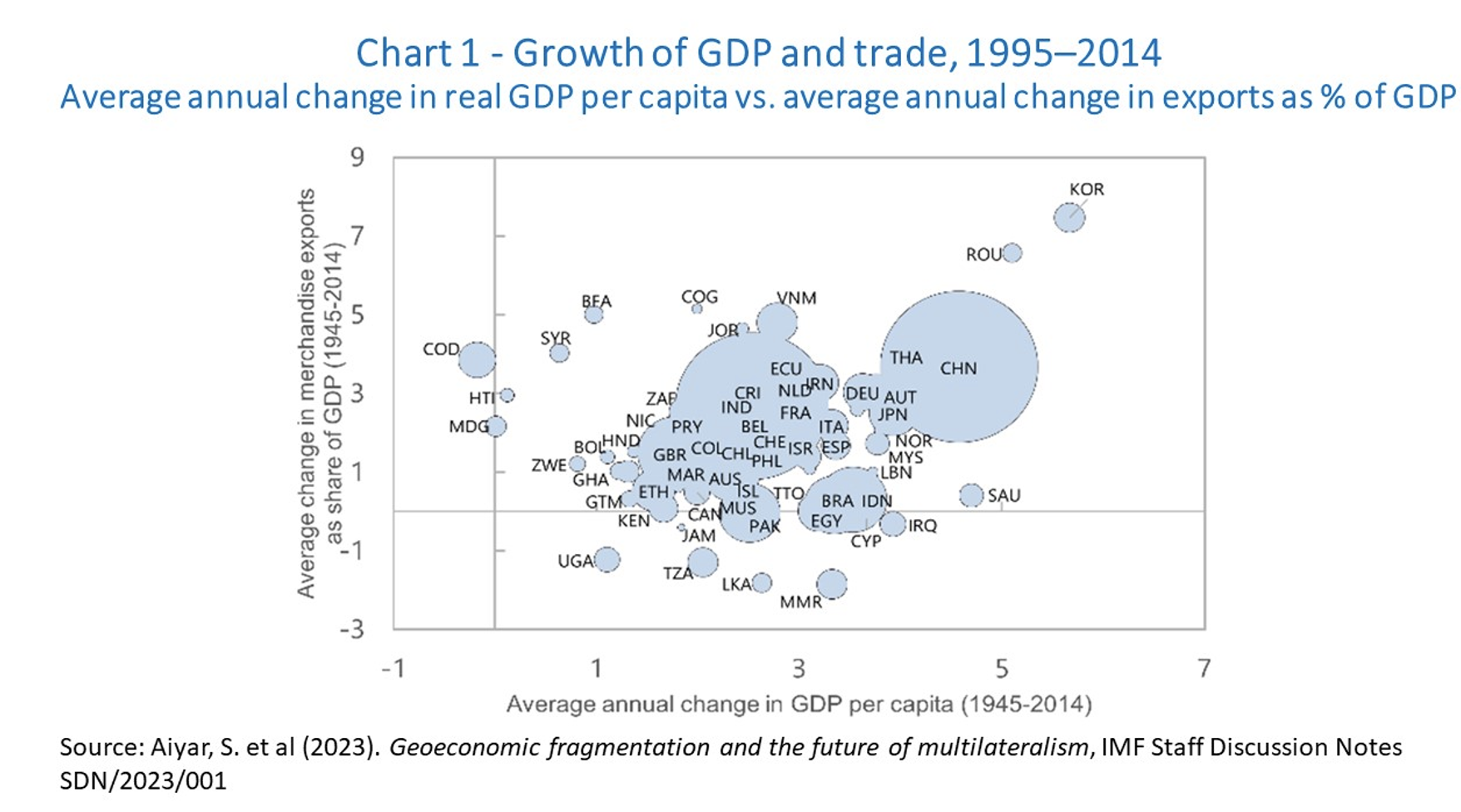

This resulted in significant reductions in poverty rates. At the same time, there was a two-way trend with respect to inequality. The world became less unequal measured by per-capita income, but there was a simultaneous rise in within-country inequality, particularly in advanced economies, as depicted in Chart 2. These were direct results of trade integration.

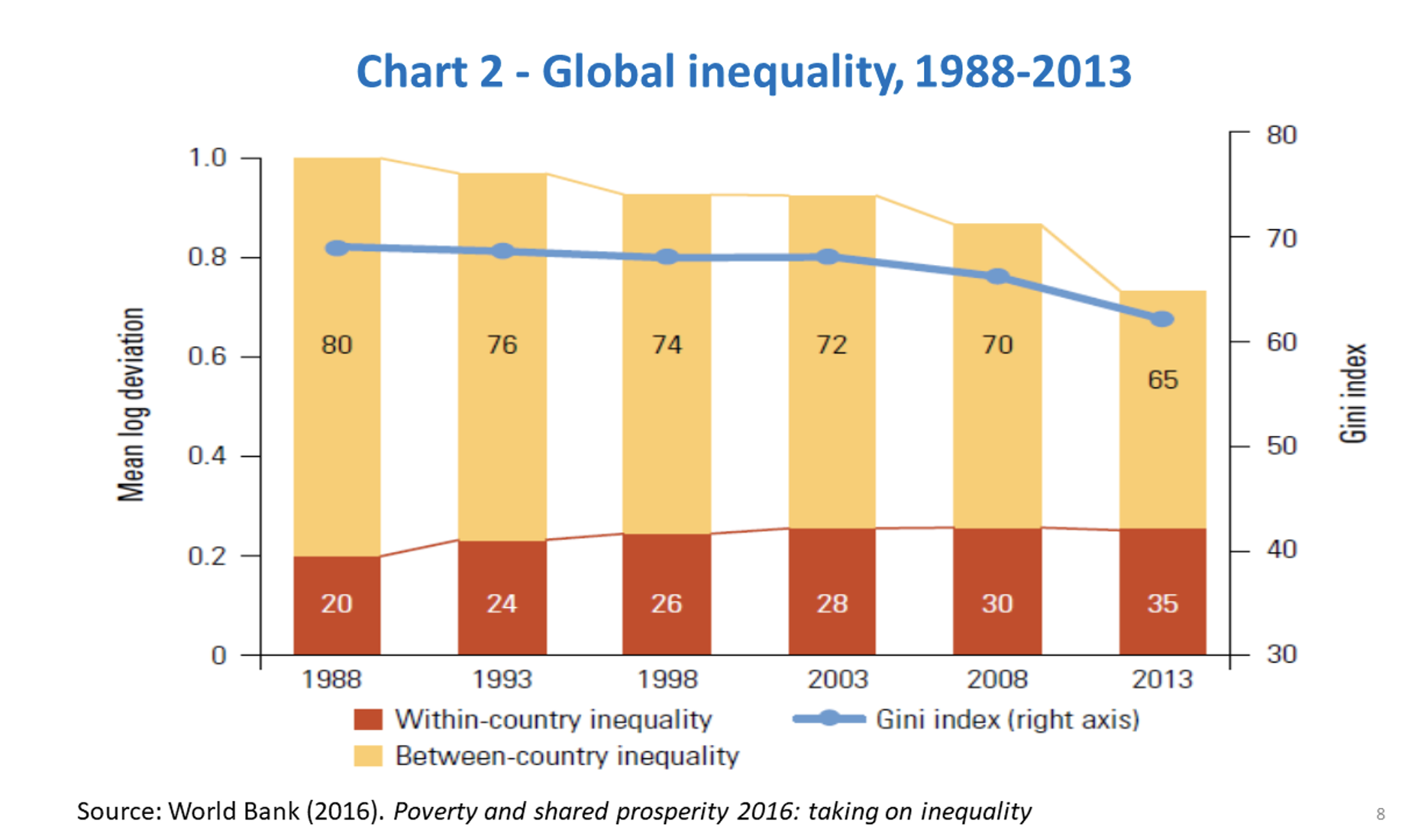

Along with higher foreign trade came the transfer and local absorption of knowledge and technology in machines, equipment, and intangible forms, accompanying the formation of global value chains. This is evident, for instance, in International Monetary Fund estimates of how foreign knowledge contributed to labor productivity growth among advanced economies and in emerging market economies. As shown in Chart 3, the IMF estimates that from 2004 to 2014, foreign knowledge accounted for about 0.7 percentage points of labor productivity growth per year, corresponding to 40% of sectoral productivity growth. This is substantial after a decade in which that contribution reached 0.4 percentage points per year.

And, before anyone thinks these results are only due to China, they are robust even when one excludes China from the analysis. China is, of course, a unique case because of its size and growth rates. But the fact is that this is an observation that can be generalized about the transfer of knowledge.

Of course, this contribution of foreign knowledge translates into better results when accompanied by domestic endeavors. As the World Bank has highlighted in many studies, there is a component of technological capabilities that is idiosyncratic and local. Capabilities must be present to utilize foreign knowledge effectively. This has been the case for countries like South Korea and China, as evidenced by their patent filings and R&D expenditures.

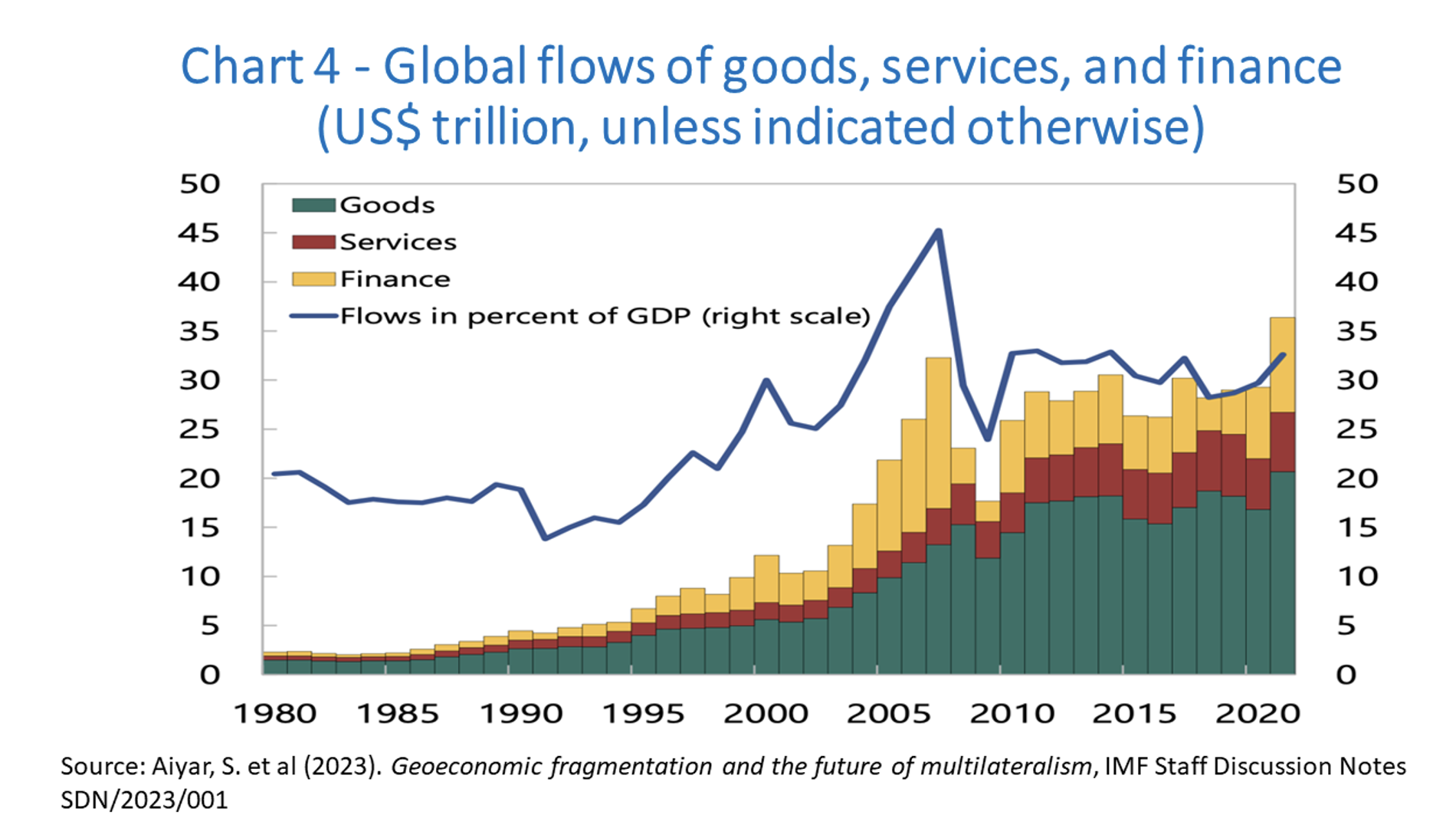

Now I turn to the phase of ‘slowbalization’. Looking in a bit more detail, we note in Chart 4 that cross-border flows of goods, services, and capital slowed after the global financial crisis. There are several hypotheses about this. One is that the major wave of fragmentation associated with manufacturing had reached a plateau. For it to continue as a driving force, we would need to see what happened in China replicated in other countries. This started to happen to an extent in countries like Vietnam. India remains the significant absentee from this process.

Another hypothesis is that advanced countries transitioned more towards service-based economies. Services are less trade-intensive, and the internationalization of services hasn't occurred to the same degree as we've seen with manufacturing.

It is important to highlight that the average industrialized country saw an increase in the Gini Index from 30 to 33 in the 20 years between 1988 and 2008, marking greater inequality. To avoid any misunderstanding, it must be clear that globalization cannot be held mostly responsible for the rise in economic inequality in advanced economies.

Technological change had more to do with that. Technological change, combined with a lack of appropriate social-protection systems in some advanced economies, is to blame for most of the worsening of job and income conditions at the bottom of pyramids in countries like the U.S. and the United Kingdom. Globalization cannot be scapegoated, despite the blaming of imports of goods from Mexico and China as responsible for the doldrums faced by low- and middle-income workers in the U.S., or the blaming of labor immigration as a reason for the Brexit decision. The fact is that globalization cannot be held responsible for that.

Then the global economy went through the recent multiple shocks, the perfect-storm combination of a pandemic, war in Ukraine, manifestations of climate change, the emergence of the so-called ‘new Washington consensus’, and the ongoing technological rivalry.

Let me touch on the impacts of those shocks. The permanent impacts of the pandemic will be limited. The pandemic raised the profile of the idea of a trade-off between resilience and efficiency. But this doesn’t necessarily lead to reshoring. If you bring back everything, then you'll remain as exposed to potential risks as you were when relying on global supply chains, given the possibility of shocks at home. On the other hand, this logic will lead maybe to some costly diversification or duplication of links depending on the sectors, but not a full reversal of globalization. As some colleagues and I showed in a policy brief for the T20 this year, the recovery of manufacturing output, particularly in technology sectors, was really nothing commensurate with the stigma established with the pandemic.

Now, where the danger lies is in the rise of national security as a determinant of economic policies. National security has been given as a justification for trade restrictions in those sectors where ‘dual use’ of technologies and goods and services for both civil and military reasons is possible. Indeed, if one looks at trade and FDI restrictions, the rise has been unequivocal, often justified by national-security reasons.

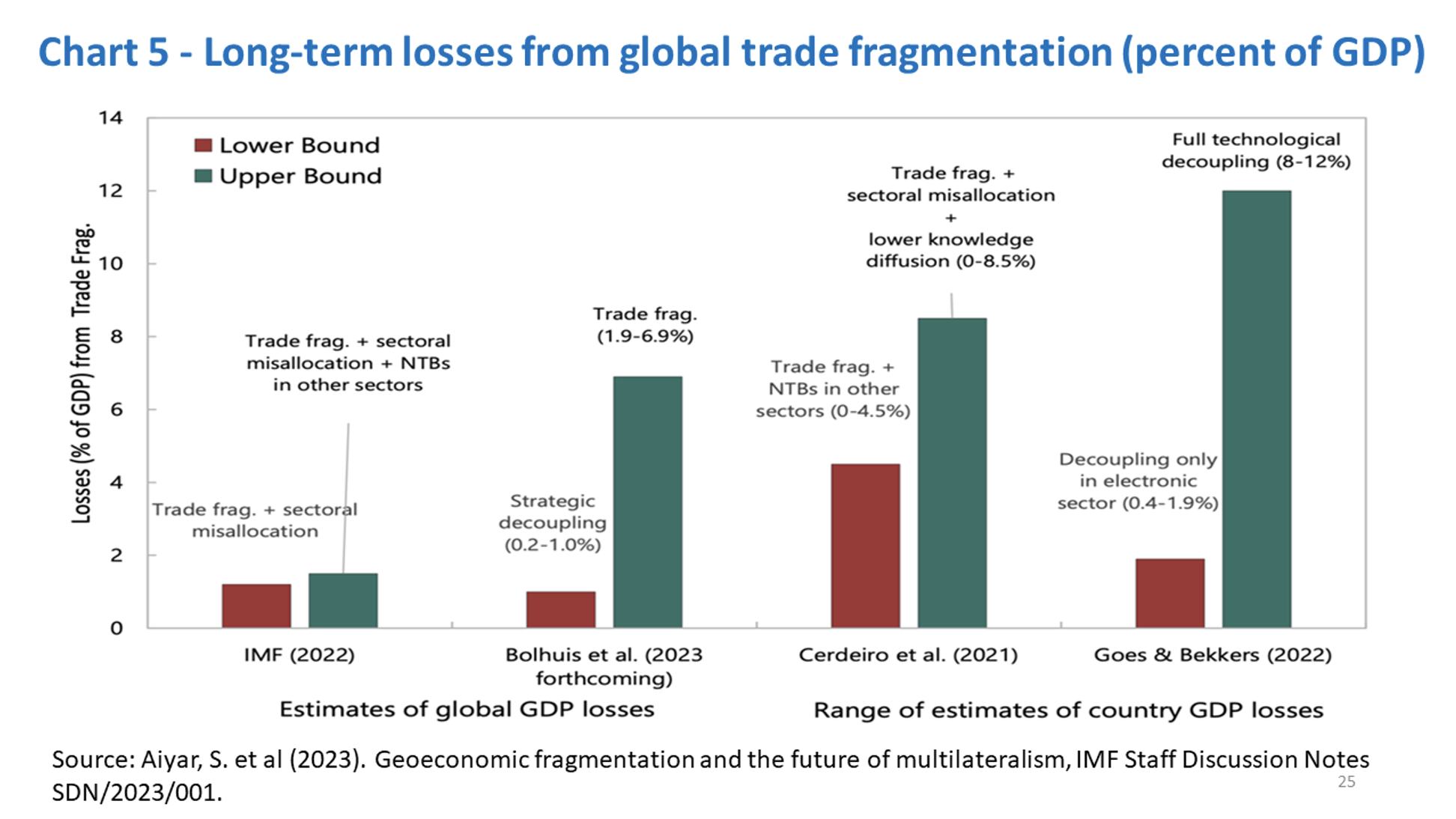

The transmission channels of the fragmentation will be a reversal of the path by which we attained the gains that we have discussed. As we are at the beginning of this process, any estimate of the costs is based on simulations from different models. For illustration, Chart 5 displays results of some studies presented in a recent IMF seminar on several models assessing different aspects of the process of trade fracturing.

One can conclude the following from those studies:

1- The costs are greater the deeper the fragmentation.

2- Reduced knowledge diffusion due to technological decoupling is a powerful negative amplifier of the trade channel.

3- Emerging markets and low-income countries are most at risk from trade and technology fragmentation.

4- Transition costs can be considerable, in some cases even exceeding the final trading impact;

5- The estimates provided are not the upper bound.

6- To finalize, the G20 might not address issues of national security directly, but there's much it can do, especially on the trade-offs between resilience and efficiency, discussing policies that avoid resorting to discretionary measures.

*Presentation at “G20 Conference: A Green and Sustainable Growth Agenda for the Global Economy”, July 28 - 29, 2023, New Delhi, India (organized by G20 2023 India, IDRC-CRDI, NITI Aayog, and GDN)