Publications /

Policy Brief

Table of content

CHANGES IN THE INTERNATIONAL ENVIRONMENT STRENGTHEN SOUTHERN ATLANTIC STRATEGIC CAPABILITIESSTRATEGIC AUTONOMY AND SOUTHERN ATLANTIC HEDGING CAPABILITIES SPECIFIC SOUTHERN ATLANTIC STRATEGIC ASSETSENERGY, CLIMATE AND FOOD SECURITY SOUTH-SOUTH DIPLOMACY AND SOUTHERN ATLANTIC COOPERATION MECHANISMSPAN-ATLANTIC CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES FACING THE SOUTHERN ATLANTICSTRATEGIC AUTONOMY AND PAN-ATLANTIC CONSCIOUSNESSThe strategic significance of the southern Atlantic is growing, driven by two underlying dynamics. Firstly, we have seen the geostrategic capabilities of the southern Atlantic states and their inhabitants strengthen and the value of their strategic assets rise, despite lingering internal vulnerabilities and frequent instability, often caused by the northern Atlantic and, on occasion, Eurasia. Secondly, the way in which the southern Atlantic states are pursuing and exploiting the potential of their growing autonomy is of great strategic concern for both northern Atlantic and Eurasian powers, as the international system is being reconfigured into something beyond uni-polarity. Furthermore, if the southern Atlantic states were to adopt a realistic perspective on the Atlantic Basin, they could easily begin to view ‘pan-Atlantic cooperation’ in certain strategic and transnational spheres, as proposed by the Partnership for Atlantic Cooperation (see Policy Brief One), as in their own best national and regional interests.

“In geopolitical terms, the ‘south’ is in the eye of the beholder.” I.O. Lesser, 2010

The strategic significance of the southern Atlantic is growing, driven by two underlying dynamics. Firstly, we have seen the geostrategic capabilities of the southern Atlantic states and their inhabitants strengthen and the value of their strategic assets rise, despite lingering internal vulnerabilities and frequent instability, often caused by the northern Atlantic and, on occasion, Eurasia. Secondly, the way in which the southern Atlantic states are pursuing and exploiting the potential of their growing autonomy is of great strategic concern for both northern Atlantic and Eurasian powers, as the international system is being reconfigured into something beyond uni-polarity. Furthermore, if the southern Atlantic states were to adopt a realistic perspective on the Atlantic Basin, they could easily begin to view ‘pan-Atlantic cooperation’ in certain strategic and transnational spheres, as proposed by the Partnership for Atlantic Cooperation (see Policy Brief One), as in their own best national and regional interests.

As mentioned previously in this Policy Report (see Policy Brief Two, footnote 6), geo-economics and geopolitics are two distinct but interrelated domains of a state’s foreign policy (or ‘grand strategy’). The effectiveness of foreign policy and the state’s power to project influence internationally in pursuit of its strategic objectives is both underpinned and constrained by its geo-economic and geopolitical capabilities. In turn, these geo-economic capabilities (access to and influence over key markets, critical resources and the rules of international and regional governance institutions) and their geopolitical counterparts (diplomatic, intelligence and military power) stem directly from and are sustained by the underlining economic strength of the country, including the economy’s size (i.e. its relative weight in the regional and global economy and its degree of internationalization), the range and depth of the resource base (including human capital), dynamism (growth rate, productivity and innovation), and resilience (degree of sectoral and international diversification, relative levels of state and civil society flexibility and adaptability). Furthermore, all these components of national economic capacity that underpin strategic influence are, in turn, impacted by the state of the domestic economic and social environment, that is the degree of the state’s policy effectiveness and continuity and levels of social stability, and by the evolution of the external regional and international environments.

There is enormous variation among southern Atlantic countries with respect to their national economic capacities, geo-economic and geopolitical strengths and weaknesses, and strategic potential and vulnerabilities. Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, Colombia, Mexico, Venezuela, Morocco, Nigeria, Senegal, Ghana, Angola and South Africa are countries that stand out in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) and Africa as countries with greater economic capacity and strategic influence than others. Yet, these countries each have their domestic weaknesses, vulnerabilities, potential instabilities and foreign policy dilemmas. At the same time, many other southern Atlantic states with even more daunting challenges and more intractable domestic instability still have the potential to increase their strategic autonomy. In the same way that a negative shift in the international environment can exacerbate or even spark domestic instability, beneficial changes in the regional and international environment provide southern Atlantic states with greater capacity to create internal change.

The previous trajectory of positive momentum toward stability and prosperity in the southern Atlantic- ----in terms of growth, development, poverty reduction and economic and political consolidation- ----was temporarily disrupted by the global shocks of the pandemic and the Ukraine war. Such shocks have exerted a negative impact on growth, inflation, debt and poverty, particularly in Africa where there are numerous wars, military conflicts, and economic, migratory and humanitarian crises unfolding simultaneously. Much of this is also true of LAC (particularly in Central America and the Caribbean basin). Meanwhile, maritime and human security risks continue to deepen as a result of the operation of pan-Atlantic ‘dark networks’ (integrating organized crime, terrorist rings and colluding state agents) that exchange illicit flows of drugs, arms, human trafficking, money, and other illegal products.

CHANGES IN THE INTERNATIONAL ENVIRONMENT STRENGTHEN SOUTHERN ATLANTIC STRATEGIC CAPABILITIES

Nevertheless, southern Atlantic countries have many strategic strengths and assets that continue to grow over time. Changes in the regional and global strategic environment-----including China’s emergence following the end of the Cold War and the more recent coalescence of the BRICS----- have continued to enhance the strategic capabilities, influence and autonomy of southern Atlantic countries.

Firstly, both African and LAC countries have diversified to a notable degree away from the northern Atlantic, not only through their growing political and economic linkages with China, in particular, and Eurasia, more broadly, but also through the multiple south-south linkages developing between the BRICS. China alone has displaced the northern Atlantic countries as the southern Atlantic’s leading economic partner. Over the last two decades, China has become the top trading partner for countries in South America, with the exception of Colombia, Ecuador and Paraguay. LAC exports to China were 1.6% of the region’s total exports in 2001; by 2020 this had risen to 26%. In the same period, LAC exports to the United States fell from 56% of the region’s total exports to 13%. LAC’s share of Chinese imports also rose from 2.4% in 2001 to 8.1% in 2020. LAC is now the largest destination for Chinese outbound direct investment (ODI), reaching nearly 50% of China’s total ODI stock. Nineteen LAC countries now officially participate in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China’s international infrastructure investment, finance and aid program across Eurasia and the Global South, while Brazil and Mexico also use it informally.

Likewise, China has also become Africa’s leading trade partner, displacing France in West Africa, and overtaking a range of other countries elsewhere on the continent. Total trade between Africa and China rose rapidly over the last decade, reaching a total of US$ 282 billion in 2022, divided nearly equally between exports and imports. By 2018, 16% of Africa’s total manufacturing imports came from China, where they had previously been completely dominated by Europe. Meanwhile, Chinese investment in Africa has surged since the turn of the century, going from US$ 75 million in 2003 to US$ 5 billion in 2021. Over the past decade, China has also surpassed the United States as the leading provider of development finance and loans in Africa.

Secondly, in addition to this relative diversification of the economic and political ties of the southern Atlantic countries from the northern Atlantic to China, the emergence, consolidation, and expansion of the BRICS Plus has provided the southern Atlantic with an alternative anchor for their strategic orientation and an additional layer of emerging multi-polarity with which to engage. This emergence of China and the BRICS Plus within the international system has3⁄4e ceteris paribus (everything else held constant)3⁄4 added to the economic strength and strategic influence of the countries of the southern Atlantic, even despite the many current and ongoing internal weaknesses, vulnerabilities, and instabilities.

Moreover, a third relevant shift in the external international environment facing the southern Atlantic countries has made itself felt recently – the Declaration on Atlantic Cooperation and the launching of the Partnership for Atlantic Cooperation (see Policy Brief One). From a geopolitical perspective, the pan-Atlantic cooperation proposed by the US-backed Partnership would, even if initially limited to only ocean, climate and related maritime concerns, provide the countries of the southern Atlantic with an initial source of leverage with which to increase their strategic autonomy. This is provided they can triangulate diplomatically and geo-economically between the powers of the northern Atlantic and the major powers of Eurasia to their own strategic benefit. The opportunities for strategic ‘hedging’ and ‘co-engagement’ may be just as pronounced in the southern Atlantic as they have been in Southeast Asia where these diplomatic tools have long been the preferred geostrategic response3⁄4both of individual countries and the ASEAN regional organization3⁄4to the competing influences of China and the United States.

STRATEGIC AUTONOMY AND SOUTHERN ATLANTIC HEDGING CAPABILITIES

During the Cold War, many of the countries of the southern Atlantic attempted to expand their strategic autonomy, with varying degrees of success, by creating the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) and the Group of 77 (G77). It has been pointed out that we are not witnessing the same phenomenon today. “The current landscape is not a reemergence of the Non-Aligned Movement of the 1950s and 1960s,” writes Len Ishmael. “Times have changed and the agenda is different”. Indeed, we are witnessing something new, something different.

The emerging coalition of the ‘Rest’7 is at least partly motivated by similar issues to those driving those earlier movements, including the neo-colonialism inherent in the Cold War strategies of the superpowers, the proxy wars they brought to the post-colonial world and a widespread desire across the Global South to avoid taking sides in the rivalries of the superpowers and the former colonial powers. In addition, the coalition of the Rest, like the G77 before it, also calls for a reform to the UN-Bretton Woods global economic governance regime. Nevertheless, during the Cold War, the material, ideological and strategic conditions were not ripe for the NAM and G77 to achieve greater success. This was the case for at least two reasons.

First, the developing third world had almost no south-south trade or investment in the 1970s. Their economies were far more integrated with the northern Atlantic than across the colonial and newly independent third world, and there were only weak linkages (as in Cuba-Soviet economic relations) between the developing world and the COMECON of the communist countries of Eastern Europe and Eurasia. Without the capacity to establish significant south-south trade independently, the G77 and the NAM had little negotiation leverage with the northern Atlantic over global governance reform.

Second, the post-colonial world could not count on its most powerful potential constituencies---- -the oil producing states, particularly in the Middle East-----for their consistent solidarity, financial support, and even political leadership in their call for a New International Economic Order (NIEO). The emergence of an enormously influential Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) remained tied to the United States and dollar hegemony via its dependence on northern Atlantic Plus consumer and financial markets, in turn reinforced by the petrodollar pact between Saudi Arabia and the United States (see Policy Brief Three). On the contrary, OPEC action can be seen as having destabilized, undermined, and divided the developing world-----through the channel of oil prices-----by contributing significantly to the third world debt crises of the 1980s and some emerging market crises in the 1990s.

However, this time around-----after the combined history of the Cold War and post-Cold War eras3⁄4 these weaknesses have become potential strengths. Today there is a much larger and increasing volume of south-south trade and other economic and political ties across the former second and third worlds. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD): “[t]he value (of South-South trade) passed from US$ 600 billion in 1995 to US$ 5.3 trillion in 2021 and its volume is now higher than that of North-South trade, growing faster than the world average. In addition, South-South trade fosters trade in non-traditional exports, including higher value- added and technology-intensive manufactured goods”.

Furthermore, a multi-continental preferential trade agreement already exists, encompassing 42 countries from the Global South with a combined population of 4 billion and an aggregate market of US$ 16 trillion. This is the Global System of Trade Preferences (GSTP). The GSTP’s Sao Paolo Round of negotiated agreements, if or when it enters effect and is implemented by all current signatories, would generate potential shared welfare gains of US$ 14 billion.10 This new reality of an emerging south-south trade dynamism lays the foundation for rising strategic autonomy and hedging capacity in the southern Atlantic. With BRICS Plus considering financial and monetary measures to de-dollarize intra-BRICS trade, the GSTP could be built upon and integrated through association with the BRICS Plus. However, it could also facilitate trade agreements across the southern Atlantic with synergies also for participation in the ‘pan-Atlantic’ Partnership for Atlantic Cooperation.

Fourth, in contrast with the 1970s, the Gulf States are now, more than ever, looking to Eurasia for economic and strategic cooperation. They could tilt the balance of power in favor of the coalition of the Rest, especially if Saudi Arabia collaborates by ending the exclusive petrodollar agreement, applying a major blow to one of the central pillars of dollar hegemony (see Policy Brief Three).

Cooperation and strategic alliances of all types in sub-regions across the BRICS sphere enhance the strategic autonomy of the southern Atlantic and its individual states and peoples.

Perhaps the countries of the Southern Atlantic now have the strategic opportunity to both collaborate with BRICS and engage in ‘pan-Atlantic cooperation’ (or even broader regional governance in the Atlantic basin). The strategic influence of Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean has, on average, never been stronger and will likely continue to strengthen should long-term trends in economics, technology, demographics and geostrategy continue, despite any short-term instability, trend reversals and lingering obstacles on the two southern Atlantic continents.

India, an original champion of non-alignment, is an important Global South and BRICS partner in this regard. The India-Brazil-South Africa (IBSA) Trilateral Forum11 was born in 2003, three years before the initial formation of the original four BRICs. IBSA provides a link between the Eurasian powers of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and the wider BRICS-sphere in the Global South, but with Africa and Latin America, in particular. India’s vocation to maximize its own strategic autonomy, particularly vis-à-vis the West and China, and its aspiration to be a ‘global swing state’12 might serve as a model for the southern Atlantic states, led by South Africa and Brazil, to bolster their own strategic autonomy and hedging capacity. Engaging the northern Atlantic states in pan-Atlantic cooperation would provide a counterbalance to the geostrategic weight exerted by Eurasian- Chinese influence and, in turn, lend Southern Atlantic actors more influence in the future shaping of BRICS Plus. Brazil, Argentina, South Africa and Nigeria, and perhaps others in the southern Atlantic, would acquire more influence over the future BRICS Plus agenda if they were all engaged together in pan-Atlantic cooperation across the North-South divide.

SPECIFIC SOUTHERN ATLANTIC STRATEGIC ASSETS

In addition to accumulating internal capacity-----growing levels of global economic output, trade and population-----and the global changes that have improved the external environment for potential strategic autonomy, such as the emergence of China and rise of the BRICS Plus, the southern Atlantic has other strategic assets whose value is rising in the current context of heightened geostrategic competition, providing greater opportunities for realignment within this new multi- polarity. These additional assets cover various geostrategic domains, including trade, sustainable development, energy, climate, resource, environmental and food security, as well as growing south- south diplomatic links and existing, often overlapping, cooperation mechanisms across the Global South and in the southern Atlantic.

Trade and development

The first of these pan-Southern Atlantic assets is the growing momentum for south-south integration on the continental scale, as regional trade integration is once again high on the agenda in the southern Atlantic. The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) was born recently. The agreement brings together 1.3 billion people across 54 Africa countries and forms a key component in Africa’s Agenda 2063. The Agenda’s objective is to significantly enhance intra-African trade and connectivity, and one of its long-term goals is to create a pan-African economic community by 2063.13 Although the continental trade area faces many future challenges, a World Bank report in 2020 concluded that AfCFTA could lift 30 million Africans out of extreme poverty, raise the income of 68 million more earning less than US$ 5.50 a day, generate net income gain for the continent of US$ 450 billion, and catalyze deeper reforms to enhance long-term growth prospects.

In the wake of Western applications of sanctions against Russia, Latin America (and South America in particular) is once again reviving its aspiration for regional integration. On May 30, 2023, 11 of the region’s 12 heads of state met in Brasilia for the first South American summit to be held in nine years to discuss a revival of the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR), proposed by President Lula of Brazil.The new agenda includes building a free trade area, creating a regional currency, and promoting continental cooperation on infrastructure, connectivity, energy and climate action.

The crystallization of these historic integration aspirations on both southern Atlantic continents could help to economically stabilize and strengthen the states and peoples of the southern Atlantic. These continental integration projects could also help to nourish and frame their own intra-southern Atlantic ties, perhaps by reinvigorating and building upon existing southern Atlantic interregional relationships, institutions and agreements between African and LAC states and regional organizations (for more, see below).

Furthermore, trends in regionalization at the global level are adding further impetus to the current momentum toward regional integration in the southern Atlantic. In its “Global Trade Update” in early 2022, UNCTAD took note of the growing global trend toward regionalism by pointing to the recent entry into force of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) on January 1, 2022. Originally a Chinese initiative, this trade agreement groups together many of the original signatories to the Transpacific Partnership (TPP) in East Asia and the Pacific to facilitate trade among themselves. However, as UNCTAD underlines, the RCEP “is expected to significantly increase trade between members, including by diverting trade from non-member countries”.

This trade diversion potentially impacts negatively, at least to some degree, other trading partners, including those in Africa and LAC. Such developments give both continents more incentive to integrate on their own.

Nevertheless, additional assets could be activated through continental integration. For example, the emerging geostrategic imperative of the northern Atlantic Plus coalition to shorten and re- regionalize critical supply and value chains into countries of the Atlantic basin also provides greater motivation for south-south integration across the southern Atlantic. To maximize the potentials of Western decoupling from Russia and China in the form of the near-shoring and friend-shoring stimulus to direct investment in Africa and LAC, southern Atlantic economies would be well served by deeper sub-basin regional integration. A southern Atlantic economic area could link the two continents together, take advantage of comparative advantages and synergies, and provide a framework for further stimulating south-south economic interaction between LAC and Africa. If pursued as a southern Atlantic regional accord within the framework of the GSTP, such an intra- southern Atlantic economic association could, in addition, provide a stronger base upon which to pursue both pan-Atlantic cooperation and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

“South-South trade has incredible potential to accelerate the achievement of the SDGs by developing countries,” according to UNCTAD. “Within the current context of multiple crises, the GSTP provides an incredibly valuable platform for addressing challenges such as climate crisis and food security through trade cooperation. A revival of the GSTP offers an opportunity for wide sectoral decarbonization in developing countries.” And, given recent changes in the global economic and geopolitical environment, “there is now a fresh window of opportunity for breaking the logjam in the implementation of the past negotiating results and moving ahead to embark on a new South-South trade agenda”.

Such developments nurture the leveraging capacity of all other strategic assets of the southern Atlantic, but could also feed broader pan-Atlantic cooperation.

ENERGY, CLIMATE AND FOOD SECURITY

The greater Atlantic basin is home to 40%-45% of both oil reserves and production. The basin also holds over two-thirds of the world’s known ‘unconventional gas’ (i.e., ‘shale gas’) resources, mainly in the United States, Argentina, South Africa and North Africa, and produces essentially all of the world’s shale gas (if mainly in the U.S.). The principal fossil fuel characteristic of the southern Atlantic, however, is its dominant position in the global hydrocarbon offshore, and especially the deep offshore (1000-3000 meters below sea level). Since the turn of the century, a southern Atlantic deep offshore oil and gas ring has developed, notably in the West African Transform Margin and in its geological twin along the Guyana offshore, as well as in pre-salt offshore formations in Brazil and their geological twins in the deep waters off Angola and Namibia. One-third of global oil production occurs offshore, and more than 60% is found in the Atlantic basin. However, more than 95% of the world’s ‘deep offshore’ production is located in the Atlantic and 70% of the global total is produced in the southern Atlantic.

After more than a decade-long exploration and production boom in the southern Atlantic deep offshore, activity leveled off as global oil prices fell precipitously from historically high levels (over US$ 100 per barrel) to historically low levels in 2014-2015 (below US$ 30 per barrel), and then remained volatile up until the pandemic, which brought about the most dramatic drop in oil prices ever into negative value terrain on the one month forward market. Prices have now returned to a level (around US$ 80 per barrel) where much more of this offshore potential is once again economically viable and, given global events, the price is likely to rise further. This makes the southern Atlantic one of the regions, at the margin of still growing world oil demand, with the most potential to supply Asia with hydrocarbons at a level beyond what can be provided by the Middle East and broader Eurasia (or the United States, for that matter).

Such strategic offshore and other hydrocarbon assets, however, have a very uncertain future in the face of the climate change imperative and the global decarbonization transition. Southern Atlantic hydrocarbons reserves and current production represent acute policy dilemmas in the form of difficult trade-offs between energy security, economic growth and social stability, in the short run, and decarbonization and other carbon action, over the longer run. Decarbonization may prove initially costly in the developing and even middle income country context (especially if pledged climate finance from the West delays), it is essential over the middle run of five to 15 years; particularly in the face of the much greater negative climate change impacts in the southern Atlantic than in most other parts of the world. Furthermore, Europe is courting Africa for oil (in the short term), natural gas (in the short-to-mid-term) and green hydrogen (in the long term) in order to meet its own short-term energy security concerns in the wake of the abrupt energy de-coupling from Russia as a result of the Ukraine conflict and the sanctions war, while at the same time attempting to maintain its own decarbonization goals. Yet it is also pushing Africa to disinvest from its fossil fuel assets and to push a green and renewable transition, even though international climate financing commitments to the developing world (as deficient as they are) remain incompletely fulfilled, as have promises so far to actually fund ‘loss and damage’.

As Rim Berahab, senior economist at the Policy Center for the New South described this dilemma: “(W)hile Europe has pushed IOCs and African countries to move away from fossil fuels, it has not accelerated funding for green projects that could provide an alternative energy source.... This risks locking oil and gas-producing countries into fossil fuels for much longer, especially in the absence of domestic policies to diversify the economy, creating stranded assets at a time when the global energy transition is underway.... (R)eductions in fossil fuel investments must be carefully sequenced to ensure that they do not outpace increases in clean energy technologies.” But she also offers some good advice for African hydrocarbons producers to take at least some advantage from this policy dilemma: “Moreover, with global net revenues from oil and gas production expected to reach nearly $4 trillion in 2022, double the level in 2021...this large financial windfall represents a unique opportunity for oil and gas exporting countries to diversify their economic structures to adapt to the emerging global energy economy and to hedge against volatile energy prices”.

At the same time there is also enormous potential in renewable energy in the southern Atlantic, alongside many other decarbonization assets. Together, Africa and Latin America claim the largest share of the world’s potential solar power resources22 and very significant wind power potential. According to the International Energy Agency, the share of solar and wind power in the African power mix is set to increase nearly 10-fold over the course of the current decade. The extension of renewable energy in Africa-----where 600 million still have no access to modern energy-----will continue to strengthen the foundation of African states’ economic capabilities, especially human resources and human capital, which support strategic capabilities. More than 50% of the renewable energy deployed in Africa this decade is in the form of off-grid solar power (e.g., minigrids).25 This ‘distributed’ (or decentralized) modality of solar power not only reduces energy poverty, avoids future emissions, dynamizes local economic activities and increases rural livelihoods, but also allows much of Africa to leap-frog an entire generation of increasingly outmoded and costly large-scale fossil fuel energy policy models and inefficient centralized national electricity systems.

The other half of Africa’s projected deployment of solar power by 2030 will be large-scale. The continent has great potential to produce green hydrogen and low-carbon hydrogen projects are underway or under discussion in Egypt, Mauritania, Morocco, Namibia and South Africa. Global declines in the cost of hydrogen production could allow Africa to deliver renewably-produced hydrogen to northern Europe (where hydrogen is projected to decarbonize the heavy transportation and energy-intensive heavy industries) at internationally competitive prices by 2030. With further declines in cost, Africa has the potential to produce 5,000 megatons of hydrogen per year at less than US$ 2 per kilogram, equivalent to the total global energy supply today.

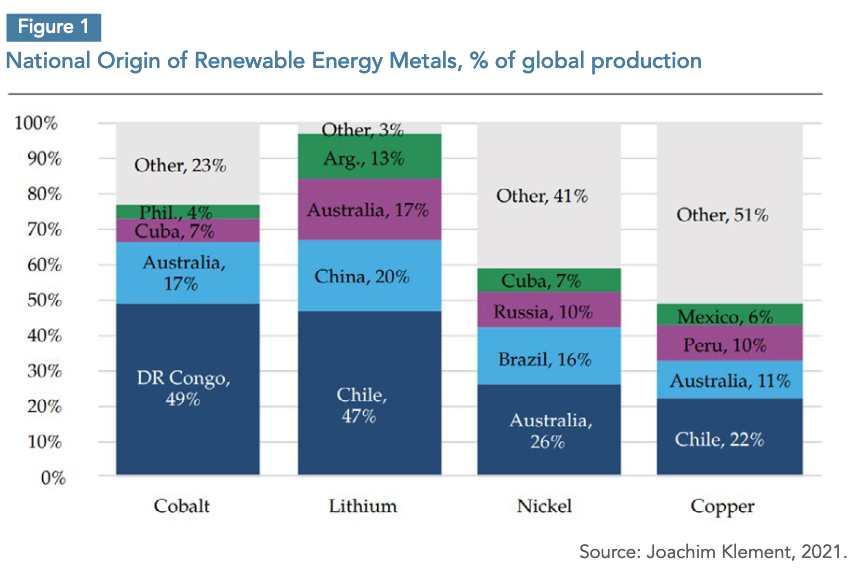

Furthermore, the decarbonization transition will increase demand several times over for a range of critical minerals. The southern Atlantic possesses large shares of current global reserves and produces many of these, including cobalt, niobium, tantalium, iridium, platinum, rhodium and ruthenium. For example, the southern Atlantic states have significant reserves of platinum group metals (PGMs), copper, cobalt, tin, bauxite and manganese. South Africa alone hosts 50% of the world’s PGM production, used in hydrogen fuel cell batteries and fuel cell minigrids, and 90% of the world’s reserves, along with 30% of the world’s manganese production and 40% of global reserves. The Democratic Republic of Congo produces 70% of the world’s cobalt, used in jet engines, turbines, batteries, and is home to half of the world’s cobalt reserves.

For its part, Latin America (Bolivia and Chile, for example) already produces large quantities of lithium, used in the manufacturing of batteries, and copper, which underpins the expansion of renewables and electricity networks. The region could expand into the mining of rare earth elements, required for electric vehicle motors and wind turbines, and nickel (which Cuba produces), a key component in batteries.29

Many of these critical minerals are not only at the heart of the military and technological rivalry between the United States and China, but could also be a key vector of cooperation among the BRICS Plus and BRICS-sphere countries, which collectively dominate the critical minerals needed for the global decarbonization transition, technological competition and military rivalry among the large powers (see Figure 1).

Morocco, in the southern Atlantic, also holds some two thirds of global phosphate reserves, providing it with key influence over global food security in the future. The pioneers of green hydrogen in Africa, led by Morocco, will contribute further to the food security value chain by using mainly renewables-based power to produce a hydrogen derivative, ammonia, for fertilizer production. The natural capital and critical resources of the Atlantic Ocean itself, especially but not exclusively in the south Atlantic high seas and seabeds ‘beyond all jurisdictions,’ also represent significant strategic assets for the entire Atlantic basin, north and south.

SOUTH-SOUTH DIPLOMACY AND SOUTHERN ATLANTIC COOPERATION MECHANISMS

Successful leveraging of this strategic potential will depend, at least in part, on the stability and cohesiveness of southern Atlantic states in their relationships with each other. Just as there are multiple layers in our currently unfolding multi-polarity, one of its potential layers – pan-Atlanticism – is also multi-layered. While the potential exists for growing pan-Atlantic cooperation across the entire Atlantic basin, there are also two contiguous sub-regions within the broader basin: (1) the northern Atlantic, the core of the West, and (2) the southern Atlantic, that long-ignored strategic space.

It is well-known that the northern Atlantic is already well consolidated through the traditional ‘transatlantic relationship,’ the NATO alliance, long-standing EU-US cooperation mechanisms, such as the EU-US Trade and Technology Council,34 and the densest, most intricate web of trans-regional flows of the global economy (see Policy Brief One). Material and immaterial flows of trade and data and cross-stocks of investment between Europe and North America (along with the density of physical connectivity infrastructure that supports such flows) continue to dwarf the volumes of other intercontinental economic and financial linkages. This includes emerging linkages between China and the West or with the southern Atlantic, particularly in digital trade, services (including digitally- enabled) and investment (stocks and flows) of nearly all types.35 The war in Ukraine has only made the ‘transatlantic relationship’ even tighter, at least apparently and at least for now. Europe’s long- standing energy dependence on Russia was being redirected even before the Ukraine war, which has only accelerated the shift, as US liquified natural gas (LNG) coming from US shale production began to replace Russian gas in Europe.

On the other hand, the southern Atlantic remains less developed, politically and economically, in sub-basin regional terms. Yet, it is anything but a blank slate. The LAC and African intra-continental ties and agreements mentioned above already exist, as does a sense of ‘southern Atlanticism’ and a pan-southern Atlantic consciousness with a certain institutional base.

Contemporary ‘southern Atlanticism’ has its origins in the Cold War period. At the petition of Brazil, Resolution 41/11 of the United Nations General Assembly in 1986 created the ‘Zone of Peace and Cooperation in the South Atlantic’-----also known as ZOPACAS (its initials in Spanish and Portuguese), SAPCZ, or ZPCSA in English-----as a forum linking South America with Africa and bringing together 24 coastal states in the southern Atlantic.

Initially, ZOPACAS served as a platform from which Brazil could attempt to keep the two superpowers out of the south Atlantic and Argentina could continue to claim its sovereign rights over the Malvinas/ Falkland, South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands. ZOPACAS typically condemned British military presence in the South Atlantic and reaffirmed the importance of maintaining the sub-basin as a demilitarized and nuclear weapons-free zone. Meanwhile, for African states the organization served as a mechanism through which to isolate apartheid South Africa.

After the end of the Cold War, ZOPACAS, now led primarily by post-apartheid South Africa and Brazil, also addressed the Brazilian-Nigerian-South African drug-trafficking nexus,40 a growing security challenge in the Atlantic basin. In addition to providing a helpful framing for stabilizing democratic transitions in parts of Africa and South America, the grouping also began to engage in environmental and maritime coordination, and to promote trade ties and cultural, or ‘people to people’, contacts.

In the wake of the September 11 attacks and the US invasion of Iraq, a second layer of southern Atlanticism began to develop through different kinds of ‘interregional’ relations. First, the Lula government of Brazil launched two attempts at southern Atlantic ‘intergovernmental transregionalism.’41 As an expansion and transformation of the previously established Brazil-Africa Forum, the Africa-South America Summit (ASA) was initiated in 2006. Further summits were held in 2009, hosted by Venezuela, and in 2013 in Equatorial Guinea. However, a lasting focus on this format seems to have weakened; the most recently scheduled summits have been postponed and the number of participants has fallen due to the rise of similar competing events.

In parallel, the first South America-Arab Countries (ASPA) summit was held in Brasilia in July 2005, with the attendance of representatives of all countries of both UNASUR and the Arab League and officials from the Andean Community (CAN), the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), and the Arab Maghreb Union (AMU). Three further summits were held, and a number of civil society cooperation and bilateral trade agreements were produced. However, the political turmoil across the Arab world in the wake of the Arab Spring, the Syrian civil war, and the emergence of Islamist militancy across much of the Maghreb and the Sahel, began to undermine ASPA’s momentum, and it has failed to reconvene since its last meeting, ASPA IV in Riyadh, in 2015.

Furthermore, ZOPACAS itself began to lose momentum after the global financial crisis and the appearance of the BRICS. Western-guided global multilateralism seemed to wane, and nationalist sentiment and inter-state competition began to reemerge around the world during the years of the Trump administration in the United States and the Bolsanaro presidency in Brazil. In 2015, the grouping adopted what was to be its last resolution for many years. Southern Atlanticism waxed and waned to such an extent that, by 2018, Frank Mattheis, a leading scholar on regionalism and interregionalism in the Atlantic basin, labeled south Atlantic relations as “volatile.”

More recently, however, a tentative renewal of southern Atlanticism was launched. This revival has revolved around attempts, led by Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay, to reactivate ZOPACAS. During the 94th Plenary Meeting of the United Nations General Assembly in 2021, a new resolution was adopted to revitalize the ‘Zone of Peace and Cooperation of the South Atlantic’ (ZPCSA), stressing its role as “a forum for increased interaction, coordination and cooperation among Member States...” Daniel Filmus, the Argentine Secretary for the Malvinas, Antarctica and South Atlantic stated that “the reactivation of the ZPCSA, following several years when no resolutions were submitted to the UN General Assembly, showcases the interest of Latin American and African member countries in protecting the region from the interests of world powers and preserving it as a zone of peace and cooperation”.

This reactivation of ZOPACAS aims to focus not only on the regional grouping’s traditional concerns with security and defense-related issues, but also on such challenges as “seabed exploration and mapping and oceanographic research, environmental cooperation, protection and conservation of the marine environment and living resources, as well as marine scientific research, among other topics”.In a presentation made at the United Nations on July 29, 2021, the Argentine government underlined “...the geostrategic nature of the South Atlantic, the importance of its incalculable natural resources for sustainable development and the cooperation between Latin American Atlantic countries and African members of ZPCSA.” Argentina also stressed the importance of the South Atlantic as a key pillar to understand climate change globally”.47 Once again, the objectives of this new southern Atlanticism anticipate and overlap with many of those highlighted in both the US and Portuguese-led joint statements in 2022 on pan-Atlantic cooperation and the subsequent Declaration on, and Partnership for, Atlantic Cooperation.

Another interregional relationship across the southern Atlantic is the MERCOSUR-SACU Agreement. The Preferential Trade Agreement between the Southern Common Market (MERCOSUR), comprising Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay, and the Southern African Customs Union (SACU), comprising Botswana, Lesotho, Eswatini, Namibia and South Africa, entered into force in April 2016. Since then, Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay have reduced their tariffs on imports from SACU members by 16.2%, 15.8%, 24.6% and 23.5%, respectively. Duties on over 63% of SACU members’ tariff lines on goods from MERCOSUR have also been either eliminated or reduced. The agreement also contains provisions on rules of origin, safeguard measures, dispute settlement procedures and customs cooperation.

More recently, the AfriCaribbean Trade and Investment Forum was launched in Barbados in 2022 to promote interregional B2B cooperation among the private sectors of Africa and the Caribbean. In yet another pan-Atlantic development, the Atlantic African States Process (mentioned earlier in Policy Brief One) is now pursuing cooperation with both northern and southern Atlantic states, infusing this reemerging southern Atlanticism with even more momentum, and framing it within a pan-Atlantic strategic perspective.

Such reinvigorated southern Atlanticism could lead to a useful sub-basin regionalism that would leverage the full potential of the southern Atlantic’s rising national and regional geostrategic significance and the increasingly valuable geostrategic assets of its countries. By working to maximize the value of these strategic assets, the new southern Atlanticism would also serve as an exercise in strengthening strategic autonomy in preparation for participation in full basin-wide pan-Atlanticism and/or collaboration with, and possible membership in, BRICS Plus. This would be the strategic ‘value-add’ of a revitalized southern Atlanticism and of multi-layered pan-Atlanticism. Indeed, southern Atlantic strategic weight and leverage is increasing in relative terms, whether a new south Atlanticism is viewed by its protagonists as a ‘stepping stone’ to authentic pan-Atlantic cooperation across the Atlantic basin, or simply as a ‘second best’ to it.

PAN-ATLANTIC CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES FACING THE SOUTHERN ATLANTIC

For the peoples and states of the southern Atlantic, pan-Atlantic cooperation across the entire Atlantic basin, north and south, east and west, makes sense not only in terms of geostrategic hedging but also in terms of the strategic imperatives imposed by multiple transnational challenges. A number of specifically Atlantic basin challenges could, if unattended, undermine southern Atlantic strategic capabilities and autonomy. At the same time, there are many opportunities which could, if addressed with pan-Atlantic cooperation, strengthen them further. These pan-Atlantic issues strategically affect the countries of the Atlantic basin more directly and immediately than the rest of the world. One could argue that this is especially true in the southern Atlantic basin. In any case, they are challenges that can only be faced and opportunities that can only be sustainably harnessed through pan-Atlantic cooperation, however pragmatic, imperfect or halting.

A short list of specific all-Atlantic basin challenges and opportunities that revolve around the ocean, and from a southern Atlantic perspective might ‘realistically’ call for pan-Atlantic cooperation, include the following:

-

‘Human security’ and ‘flow security’, both increasingly precarious in the face of pan-Atlantic ‘illicit flows’ and Atlantic basin ‘dark networks.’49

-

Atlantic Ocean regulatory and policy cooperation, especially in zones beyond all jurisdictions (BBAJ) in the high seas, particularly in the areas of:

-

maritime security50 (important also for human and flow security).

-

sustainable development of the Atlantic ‘blue economy’51 (including Atlantic cooperation

of deep seabed mining and genetic harvesting).52

-

Atlantic marine environmental protection (particularly unique or endangered types of

ecosystems, coral reefs, etc., which are tightly linked to both the biodiversity crisis and the

dialectic between oceans and climate change).

-

Atlantic coastal ecosystem protection, restoration, and management.

-

-

Pan-Atlantic cooperation on sustainable development, energy and the decarbonization transition.

-

Atlantic digital security cooperation, including subsea cable security, planning, deployment and maintenance collaboration.

-

Atlantic basin collaboration amongst Atlantic ports and port cities, crucial platforms for economic, security and regulatory activities relating to decarbonization, digital transformation, sustainable development and security within the ocean-maritime sphere

STRATEGIC AUTONOMY AND PAN-ATLANTIC CONSCIOUSNESS

If the peoples and states of the southern Atlantic were to more fully revive southern Atlanticism, and at the same time consider pan-Atlantic cooperation across the Atlantic basin, they could perhaps generate the conditions for greater strategic autonomy than they have ever enjoyed, at least since the Portuguese and Spanish voyages. Back at the dawn of pre-industrial globalization in the 16th- 18th centuries, the southern Atlantic was arguably the most strategic zone of the nascent global system. This was the period of the so-called ‘Atlantic system’, often referred to as the system of ‘triangular trade’, even though the overlapping European colonial economies established trade along all six Atlantic basin trade vectors.

As a by-product of this colonial ‘Atlantic system’, an early and perhaps original expression of nascent ‘pan-Atlantic’ consciousness was born and then spread across much of the basin. This phenomenon was stimulated largely by the diaspora created by the ‘Middle Passage’ along all the vectors linking Africa with the other Atlantic continents. The pan-Atlantic legacy of the Middle Passage diaspora has never died and has recently been reinvigorated, as its arts, business, innovation and politics have continued to engage in pan-Atlantic exchanges, associations and fusions, with many recognizing a ‘Black Atlantic’ or an African Atlantic, revealing a pan-Atlantic consciousness amongst many people in the diasporas, the descendants of the slaves of the Middle Passage.55

Over the centuries, the pan-Atlantic African diaspora has made many significant contributions to the peoples and states of the Atlantic basin. African diaspora branches across the entire basin have etched an indelible mark upon the political, economic and cultural consciousness of nearly all the peoples and states of the Atlantic basin. The African diaspora has the potential to stimulate other pan-Atlantic diasporas, along with many diverse Atlantic cultural sources, into an overlapping, more developed and more mature Atlantic basin consciousness.

“The new and highly unsettled strategic environment,” Ian O. Lesser wrote more than six months after the outbreak of the Ukraine War, in reference to its knock-on effects in the southern Atlantic, “will raise new questions about Atlantic history, including the dark periods of slavery and colonialism, when the southern Atlantic was the center of economic and geopolitical competition. When north and south assess the shifting balance of insecurity, much cultural and historical baggage will be revealed”.56 This shift in the assumptions of the North-South discourse will increase the capacity of the African diaspora3⁄4which embraces the entire basin-----to augment and recast the stories, visions and perspectives previously predominant in the northern Atlantic. It would also go a long way in helping to overcome the Atlantic north-south divide by providing a truly pan-Atlantic character.

Although there are other diasporas present in the Atlantic basin, none are as extensively pan- Atlantic as the African diaspora. At the cultural level of soft power, this historical rebalancing of the perspectives of the Atlantic basin and its nascent consciousness becomes a cultural strength, and strategic asset, of the southern Atlantic that will have synergies with its rising strategic influence and weight.

PAN-ATLANTIC COOPERATION AND SOUTHERN ATLANTIC STRATEGIC AUTONOMY

Through pan-Atlantic cooperation, the southern Atlantic would gain leverage with the West, and with the northern Atlantic within the basin. The southern Atlantic will increasingly be capable of pro-actively overcoming the Atlantic north-south divide by using its rising influence within the West to nudge the northern Atlantic onto new or more accelerated paths of reform, change and transformation, particularly with respect to international cooperation on climate-related challenges.

This strategic ‘nudge’ capacity could, for example, be used to pressure the advanced economies of the West to assume additional burdens regarding climate change, especially climate finance where commitments from 2009 to provide US$ 100 billion a year in climate finance to developing countries remain at least partially unfulfilled, and to engage in a debt-for-climate-action-exchange with the southern Atlantic countries. This could be especially beneficial in Africa, where debt levels in the wake of pandemic disruptions, the Ukraine war, the imposition of Western sanctions on Russia, and the tightening of interest rates in the United States, have begun to approach those of the Third World Debt Crisis of the 1980s.

There is now a concrete proposal coming out of the southern Atlantic: the Bridgetown Initiative, launched by Barbados and championed by Mia Mottley, the island’s first woman prime minister. The Initiative proposes to reform the world of development finance, particularly how rich countries help poor countries cope with and adapt to climate change. The Initiative proposes three specific measures: (1) suspension of interest payments during periods of disasters; (2) an addition US$ 1 trillion in concessional lending to developing countries for building climate resilience; and (3) the creation of a Global Climate Mitigation Trust, with private sector backing, that could leverage US$ 3-4 trillion in private funding for climate mitigation and reconstruction after climate disasters.

Moreover, the southern Atlantic would also gain leverage with China, Russia, India and Eurasia, and within the broader BRICS Plus. Through pan-Atlantic cooperation, which would likely revolve principally, at least initially, around Atlantic Ocean-specific issues, particularly climate change- related challenges and opportunities, the southern Atlantic would be in a position to strategically hedge between Eurasia and the northern Atlantic. For example, any challenge to dollar hegemony will depend not only on the basic fundamentals and design of such a BRICS Plus currency and the internal cohesion of BRICS macro-economic policy collaboration, but also on the potential strategic reach and scale of the monetary geography of those challenging the new currency. This is because broad reach and scale are required to overcome the enormous and resilient incumbency power of the hegemon within an ‘asymmetric network,’ like the dollar within the asymmetric network of monetary power (see Policy Brief Three).

For any future BRICS Plus currency to achieve the critical mass necessary to capture increasingly larger shares of the network of monetary power, the southern Atlantic states will need to become increasingly major participants or users. This would give them strategic leverage in any future negotiations over the creation, design and management of a truly balanced BRICS Plus currency.

Indeed, the opportunity for the southern Atlantic to strategically hedge the interests and influence emanating from the powers of Eurasia and the northern Atlantic through participation in both pan- Atlantic cooperation and the expansion and consolidation of BRICS Plus is actually an opportunity for the peoples and states of the southern Atlantic to have a real influence in shaping the ultimate topography of the global system that will finally emerge from the current erosion and breakdown of hegemonic uni-polarity. Will it be an international system of geostrategic competition or international cooperation? Will the historic north-south divide in the Atlantic be overcome? As Ian O. Lesser foresaw, over a decade ago: “...the debate over the reform of global governance is likely to be played out, in large measure, in the south Atlantic, with South Africa, Brazil, and perhaps Nigeria as key advocates for change”.

In this sense, the southern Atlantic constitutes a geostrategic hinge between a potentially successful pan-Atlanticism and a BRICS-based geostrategic association of the Rest within an evolving multi- layered multi-polarity. Of course, potential southern Atlantic geostrategic leverage would be enhanced significantly by the end of the petrodollar agreement and any movement towards a BRICS Plus currency mechanism.

How the southern Atlantic countries handle their relationships with the powers of Eurasia, on the one hand, and the powers of the northern Atlantic Plus on the other, particularly in the wake of the Declaration on Atlantic Cooperation and the expansion of the BRICS, will be key in determining exactly who gains most from the rising strategic value of the Atlantic basin, and of the southern Atlantic in particular. Will it be the Eurasian powers, the northern Atlantic powers, or the countries and continents of the southern Atlantic? Will it be a win-win or a zero-sum game?